5 Moronic Predictions About the 2024 Boston Marathon—And Why You Should Bet All Your Bitcoin They'll Come True

Anyone who forecasts Boston Marathon results correctly has merely made lucky guesses. Instead of boring prediction contests, we need to pray for untethered whimsy and nontraditional unforced errors

When a marathon footrace gathers world-class fields, predicting the results is nothing but a guessing game, something by definition no one is especially good at compared to anyone else. This is because anyone who cares enough about elite distance running to stray into such aberrant analytical behavior operates in the same general way: Assess the personal bests of everyone involved, pretend everyone is in precisely PR shape, additionally pretend that all of those personal bests were achieved on similar courses using similar strategies, and create an assortment of defensible justifications for stratifying these athletes into highly granular race-day ability categories.

Yet publicly posting predictions about marathons with world-class fields is always a safe bet for the house, unless the house is too honest. This seems paradoxical, but think about it: because every running pundit both knows that marathon prediction-games are crapshoots and is obligated to produce them anyway, when someone’s guesses prove mostly on-target, he can concoct post hoc rationales for why he was more certain than he was; but when the same person badly misses the mark, he can say, “Well, we always knew anything can happen” or simply never reference his forecasting pratfall.

The Boston Marathon adds even more analytical mayhem than most top-class 42.2K road races owing to its rolling course, which pounds elite runners’ legs in hard-to-foresee wats, and that course being ineligible for world records, meaning that no official pacesetters grace (or besmirch) Boston fields.

Still, since sending thoughts and prayers at the athletes no less a waste of energy than predicting how they will perform, it makes sense to bear down and implore the cosmos to compel multiple top-seeded runners at today’s race to depart the starting line in Hopkinton, Massachusetts at methodically reckless paces. Not only do the meager course records—2:03:02 for men and 2:19:59 for women—need to be broken to save the sport itself, but they need to be demolished by literally insane margins that will shatter the entire Internet, full stop. Nothing else will keep the Boston Marathon worthy of inclusion as a World Marathon Majors event, and such an unforeseen development might even return the race to the same competitive league as the London Marathon, this year’s edition of which takes place on Sunday.

Few to no sane arguments against this proposition exist, but as a bulwark against others’ tiresome bullshit, Beck of the Pack has formulated a spectacular array of irrefutable talking points favoring a hyper-ambitious pace by at least a few gamely feverish souls and perhaps the entire invited field. One of these points—real talk, yo—is being unable to count on the certainty of future Boston Marathons because of the degenerate antics of senile, sociopathic politicians and their sleaze-lord, blackmail=happy puppeteers. The other is the expectation of favorable conditions.

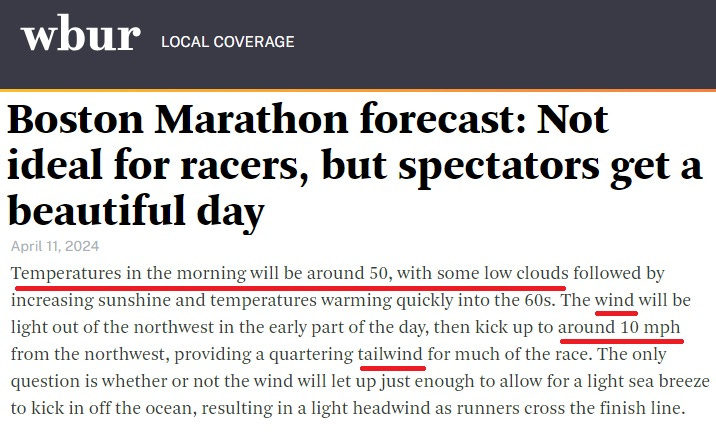

On Thursday, a local news station declared that a partly cloudy days with temperatures in the fifties for the elites and a following wind was “not ideal for racers.”

That forecast generally holds, except that the wind out of the WNW is supposed to be blowing at only around 5 miles per hour through the various towns along the route.

[NOTE: The following section has been corrected. In the original post, the angle subtended by the relevant lines was given as 60 degrees.]

The predicted wind vector is offset from the ENE (or, equivalently for present purposes, WSW) vector of the course by (roughly) 45 degrees. If these assumptions hold, the effective tailwind for the runners will be about 70 percent (1 divided by the square root of 2) of whatever the average measured wind speed is.

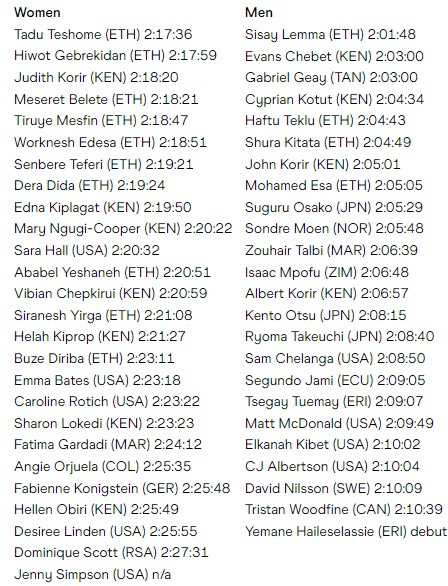

A 2- to 3-MPH net tailwind is a modest boost but better for the runners than still air, and the elite fields include three men and eight women who have run faster on loop courses—where enjoying a tailwind throughout is difficult to pull off—than the Boston course-record times.

Since we can assume that Sisay Lemma is currently capable of a 2:01:48 and no faster, an opening half at the pace (1:00:54) would leave feeling fresh in Wellesley even without the 300-foot drop the Boston course will provide him. And a 1:00:54 effort on the flats has to be worth under an hour on the Boston course. Lemma, or someone with gumption, should make a point of passing through the halfway point on sub-two-hour pace, running even 4:33 miles the whole way. Failing that, a 1:00:19 first half would still put someone on pace for the fastest official marathon ever run, even if the course is not world-record-eligible. (Kelvin Kiptum already feels like a bizarre, not-fully-parsed phantasm.)

Limping home in a little under 1:03:00 after that is practically a given provided Lemma retains faith in himself, relaxes his arms on the climbs and descents, and doesn’t make any sudden moves, including stopping as a consequence of substate unavailability, producing exhaustion, delirium, and possibly the shits. So be it. The men’s course record has now stood for an outrageous thirteen years—itself a record.

The fact that brazen frontrunning has never worked for a single Boston Marathon elite runner who has tried it should be regarded not as a warning but as a quaint strategic carryover from a bygone aerobic-biomechanical era and hand-waved out of consideration. The racing flats on athletes’ feet today don’t make them impervious to the bane of downhills, but they make enough of a difference to make anything possible when used as intended.

Besides, a lot of previously solid assumptions about the competitive resilience of world-class perambulation-machines seem to have evaporated lately without fanfare or even comment. Remember when it was widely assumed that top collegians and pros alike needed a rest between, say, early December and mid-January, and then another between indoor track and around early April? Now it seems like there is no break at all. The December Boston University Sharon Collyer indoor meet right after NCAA cross-country season ends has become a locus of otherworldly 5,000-meter times, and eight men broke 27 minutes for 10,000 meters at The Sound Running TEN on March 16.

Over 20 years ago, Scott Douglas wrote a profile of George Young, the American 5,000-meter specialist who qualified for four U.S. Olympic teams. I can’t find the piece, but a Letsrun forum poster preserved exactly the part I was looking for:

"I trained with speed year round," he continues. Indeed, much of his 5,000 miles a year was metered out in lung-searing 330- and 440-yard repeats. "Now, I hear about needing a break after the Olympics, then building a base," he harumphs. "That's three or four months out of the year when your training isn't what it should be. You can put in your six weeks of base, then start speedwork and get sore and stiff, or you can get out on the track the first day and get sore and stiff and get it over with.”

Young also broke four minutes for the mile for the first time when he was thirty-four years old, an age that in 1972 was banging loudly on the door of geezerhood.

With evidence for the viability of hammering from the gun today thus established for the men, we can apply it to the even-stronger women’s field. At least three Ethiopian women should begin their journey at a steady 5:08-5:09 pace and plan to rip through the opening half in 1:07:30. If at least one of them can’t come back after than over the “hills” in faster than 1:12:29—not even 5:30 pace—then all involved are probably in the wrong sport.

The wheelchair racers should try the same thing. I’m pretty sure all of these characters are using wireless technology to cheat. Their chairs could all be fitted with small, well-concealed onboard computers, which could be used to power discreet motors hidden inside the camber bar on demand. Each wheelchair racer could have a handler monitoring his or her progress via their GPS coordinates (matched to elevation) and their biometrics, and activate the motor remotely to create the equivalent of a covert e-bike.

Also, consider the effects of increasing cardiac output in someone who dedicates little or no blood circulation to their lower extremities. The hemodynamics in such an athlete are uniquely extraordinary, and none of them should be shying away from inotropic agents. Wheelchair racers have been familiar with a range of standard catecholamines for years, but perhaps vasopressin and phosphodiesterase inhibitors are finally in the enhancement conversation, too.

A commenter recently raised awareness of another Boston Marathon elite-runner issue. Two years after Rita Jeptoo won the 2014 edition of the race in an apparent course-record time of 2:19:00, Jeptoo was disqualified for a doping violation and her result annulled. However, the woman elevated to first place after Jeptoo’s disqualification, Buzunesh Deba, has yet to receive the $100,000 the Boston Athletic Association owes her as a result.

Izzie Nutz summed up the B.A.A.’s “plight” in a subsequent comment:

For a race that charges $275 entry fee despite having two mammoth sponsors like John Hancock and adidas, it's despicable to hint that they need to get the prize money back before paying the rightful winner. And how could a race sponsored by a major insurance company not have insurance to cover fraud? Didn't Rosie Ruiz run off with the laurel wreath just a few years ago???

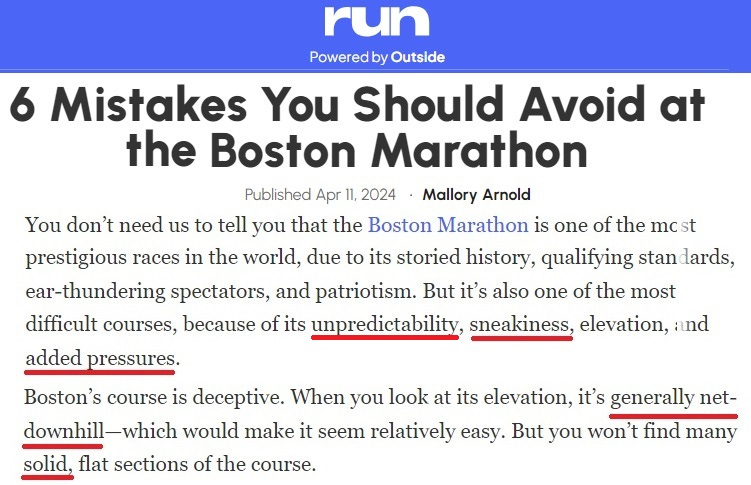

Meanwhile, in the service of mid-pack-caliber runners, Mallory Arnold of RUN (powered by Outside) produced a list of a half-dozen no-nos to avoid on the Boston course today.

While I and many others are guilty of calling abstract concepts or inanimate objects “tricky” or “sneaky,” using the noun forms of such adjectives imparts an extra layer of anthropomorphizing to the description. That said, the Boston course is indeed known for its unpredictability and sneakiness. One year—and you can Google this—it decided to take a multi-lane bridge on Commonwealth Avenue over I-95 and reduce it to a six-foot-wide dirt path that had noisy tropical birds squawking away in lush trees on both sides, like a taste of Amazon country. That created quite a bottleneck once the pack runners got to Kenmore Square. I think the course sobered up in 2008, though, so over-the-top pranksterism that puts added pressure on already strained athletes is mostly in the Boston layout’s mercurial past.

"Generally net-downhill" is a new one, too. I’ve always assumed that “net-downhill,” while an absolute descriptor, and “generally downhill” mean the same thing—more downhill than not. “Generally net-downhill” seems to mean “with a lower finishing point than starting point, for the most part.” This is kind of like saying that 2 + 2 = 4 in all situations in which 2 = 2. I like it.

I also wonder how Arnold—who I hate to lump in with the other clowns at Outside because she seems like a nice, earnest gal with no functioning co-workers—settled on six unforgivable mistakes when marathon runners are famously capable of committing a dizzying range of procedural miscues.

With this in mind, here’s a preview of a story I’m editing meant to complement Arnold’s about the ill-advised things you can in fact do to negate months of devoted and intelligent training, errors best achieved once a sufficient number of leering eyes are training their collective Internet gaze on you.

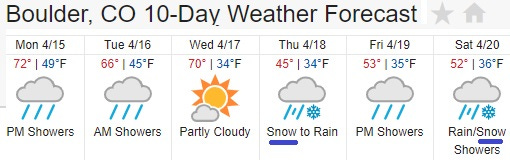

There is a story, sort of, underlying the image on the right:

Whatever the conditions yield in eastern Massachusetts today, it looks like the weather gods overseeing Boulder are opting this week for the “let’s ensure a glut of May flowers” route. I plan to just run a little faster from the start of all of my runs to stay mostly dry and warm.