A blurt about recent predictions, both declared and narrowly avoided

Jakob Ingebrigtsen and his countryfolk are easily the whitest de facto Ethiopians in history

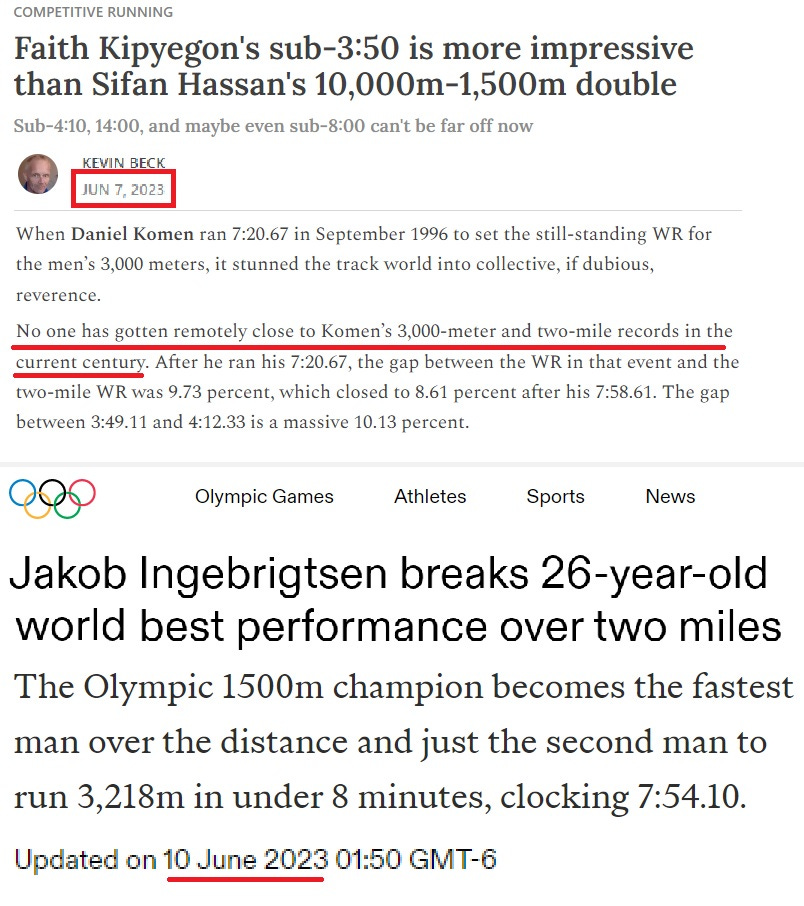

The other day, I noted not only how old Daniel Komen’s two-mile world record was, but also how impervious that record (7:58.61) had remained to meaningful challenge since Komen established it in 1997, not counting Komen’s own near-hit the next year.

I made that post just in time for this observation to be nullified, with prejudice.

It’s probably just as well that I didn’t know about Jakob Ingebrigtsen’s impending attack on the record, because I believe I would have speculated that Ingebrigtsen would break eight minutes but miss either of Komen’s two fastest times. In other words, I would have forecasted a 7:59-something.

I would have been off by an incredible five seconds. And the incredible part obviously wouldn’t have been me screwing up a prediction by a sizable amount, which is a regular occurrence. It’s that 7:54.10 is easily the best performance of the precociously decorated Norwegian’s career, just outperforming, on World Athletics points, the world records in the 1,500 meters, 3,000 meters, and 5,000 meters while falling just outside Joshua Cheptegei’s 10,000-meter global standard.

Ingebrigtsen’s equivalent times in those five events, followed by the corresponding world records:

3:25.91 (3:26.00), 3:42.25 (3:43.13), 7:20.00 (7:20.67), 12:34.87 (12:35.36), 26:12.21 (26:11.00)

Not only is the time objectively remarkable, but outdoor world records in distance events traditionally haven’t start falling—or being cemented for a given year, anyway—until the official onset of summer:

World-class athletes have had access to Nike ZoomX track-spike technology since 2019, so any technology-specific jumps have already had time to occur. Similarly, any theories about pandemic-specific training benefits to athletes, while nonsense from the start, have expired and begun amassing invisible dirty-urine stains. Ingebrigtsen has been a Scandinavian lab-experiment since the time he was a pre-teen, and now we’re* seeing the rollout of the prime phase.

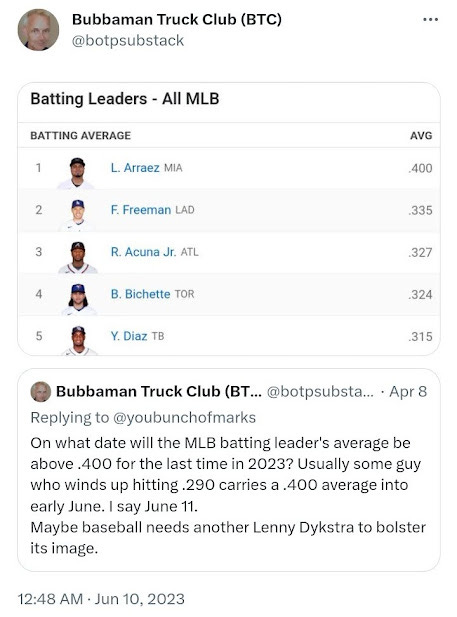

If we equate a non-prediction with a firm prediction, this is somewhat related. Early in the current Major League Baseball season, I speculated that someone destined to not bat .400 for the season (it hasn’t been done since 1941) would keep his batting average that high through June 11 before succumbing to ineluctable reality.

This summed up the situation going into today’s games:

Luis Arraez went 2-for-4 today in Miami’s 5-1 win over the Chicago White Sox, raising his average to .402 and ensuring that he will carry that average into June 11. He will need to go 0-for-2 (or 0-for-3, etc.) or 1-for-4 (or 1-for-5, etc.) tomorrow against the White Sox to fall below .400.

The wild thing about Arraez’s 2023 is that he was batting .438 after 25 games at the end of April, then slid to .371 on May 24. He was still at only .374 after going 0-for-4 on June 2, but then went on a five-game, 14-for-21 tear to scramble his way back to .403.