A quick take on quick takes: The media's symbolic effort to overturn Shelby Houlihan's settled doping case

Even I didn't think the drones would botch this so extravagantly

Yesterday, the Portland-based, Nike-operated Bowerman Track Club announced that Shelby Houlihan, the American record holder in the 1,500 meters and the 5,000 meters, had tested positive for the banned steroid nandrolone in December. In the interim, Houlihan’s legal team, eager to resolve the case in time for the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials, unsuccessfully appealed the positive result, claiming that the steroid had come from “authentic Mexican” burrito meat purchased in Portland, a city in the northern U.S.

In other words, by the time the announcement was made during a Zoom call that included multiple members of the goon squad composing most of today’s running media, Houlihan’s was a closed case. Barring an extremely unlikely intervention by a Swiss court, Houlihan will now serve out a four-year suspension and miss the 2021 and 2024 Olympics. It’s not a certainty that her career is over, but as FiveThirtyEight might put it, her path to a favorable outcome is torturous and statistically bleak.

This is an important contrast to most previous revelations of positive doping tests I’m aware of; these typically become public before the athlete has completed or even begun the appeals process. In those cases, extending a certain amount of latitude to the athlete makes sense, given what may turn up on appeal, even when brazenly porous excuses are offered up to explain the tainted pee.

But in this instance, it’s all over. The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) exists to deconstruct the validity of appeals, and in this instance they manifestly found none. I imagine this will turn out to hinge on Houlihan’s sheer blood levels of nandrolone metabolites, but for scoring purposes it doesn’t matter. There was really nothing left for Houlihan and the BTC—and with them, running fans and the running media—to do starting yesterday afternoon besides either quietly accept the result as valid or go on a public-relations counteroffensive in an effort to, in the court of U.S. running-public opinion if nowhere else, invalidate it.

Unsurprisingly, the BTC chose the latter strategy, with most of its members taking to social media in a blitz of support for Houlihan’s and BTC head coach Jerry Schumacher’s vigorous, almost slapstick condemnation of the suspension. Schumacher saying he had never heard of nandrolone almost makes me wonder if he was paid to do the rhetorical equivalent of taking a dive to the canvas in the third round. Sheesh.

Some BTC members took firm anti-doping stances when Alberto Salazar was suspended and the Nike Oregon Project across town was dismantled, even though no positive tests for banned substances were ever announced for NOP athletes. (I phrased it that way for a two-word reason: Testosterone cream.) There is no real need to delve into the selective comments by these or any athletes, because my concern, as always, is what the media is saying. And the media, in the least startling development in the whole sad drama, has, despite whatever the CAS has found in rejecting the appeal, formed a unified front behind Houlihan and her Instagram tale of woe.

I’ll preload my survey of the media’s responses with a loaded question: If you considered yourself a journalist by trade and were therefore, at least in theory, interested in getting and communicating the truth at any cost, what would concern you more: Saying something sensible but so controversial that it might cost you access to an entire club of elite defiant athletes, or stifling both your instincts and your morals and opting to function as a Nike public-relations bullhorn instead?

I know which it would be for me, and that’s largely why I’m now an industry pariah writing on Substack. But for “journalists” whose only crystallized aim is looking as good to as many important people as possible in as craven a manner as can be imagined, it’s just as much of a no-brainer in the opposite direction: Screw those testers! Haven’t they read studies about boar testes from 2002?!

The stories below hit the Web almost immediately after the Zoom call ended. In other words, they were snap judgments. And almost to a one, despite Houlihan’s case being closed, they urged readers to avoid a rush to judgment, despite that judgment having already been officially handed down. This behavior would be hilarious enough on its own, but is rendered farcical beyond description by these same “let’s be fair” hammerheads being the architects of “Cancel Laz for nothing!”, “This announcer is calling women fat!”, “Boys are girls too—end of discussion!” and other top-10 Wokish hits from 2020.

This, here, is my main point, so please don’t get lost in my mockery of the support of Houlihan per se. Hypocrisy is rarely a valued trait, but in anyone claiming to be a journalist, it’s fatal. Even if running is too nebulous and fringe among sports to oust the posers from their posts in editorial and uber-freelancer positions, it nevertheless leaves each of them looking like some combination of dupe and ignoramus.

Some, I know, are keenly aware that outside the “likes”-rich echo-chamber of their own rhetorical toilet bowl, each of them individually looks like an addled child in reaching far into their asses to defy reality, which they often do at the expense of someone’s reputation, eating-disorder sufferers’ well-being, and others in the running community they purportedly serve. But for now, these incompetent aspirants to personal renown at any cost are protected by their sheer number and by the smooth, systematic simultaneity of their shrill and bungling lies, slurs, and distortions; they fail all tests of reasoning power and courage, both of which sunder their efforts at playing journo more than their unconditional, slavering love of their interview subjects does.

Chris Chavez, in on the Zoom call, wrote an article for Sports Illustrated with a headline stating, as settled fact, that the positive test resulted from food ingestion. In other words, this guy claims to know something the CAS didn’t find.

This is no different, structurally, from writing about a murder conviction, and repeating the words of the defense lawyer—”He thought it was a squirt gun,” maybe— that had, mere moments ago, failed to persuade a jury or a judge. There is taking a side, and then there is just being a colossal, beaming idiot.

Chavez should, in all honesty, find something else to do with his life if he can’t stop infusing everything he says with bullshit. SI used to be not just readable, but a literary treat. From The Life of Reilly to this crap?

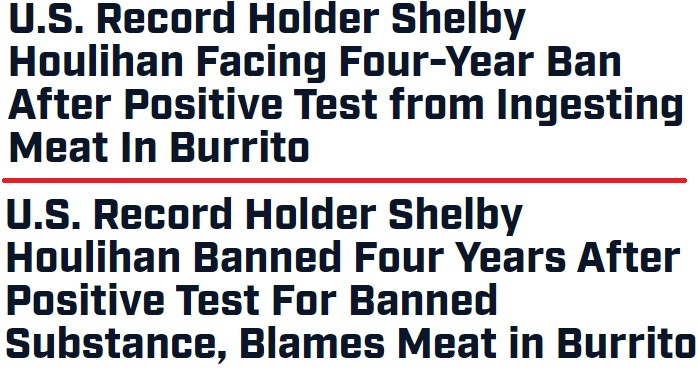

[Update: The SI headline has been changed, without acknowledgment of its previous composition. Here are two headlines together in their order of publication. The difference is not merely substantial—it’s everything.]Women’s Running had an interesting headline for Erin Strout’s obligatory apologetics piece presented as a story:

Portraying a four-year ban as merely missing the Olympic Trials is like saying that someone just sent to prison for murder is going to miss his daughter’s birthday party next week. True, but can we* strain any harder to stave off reality? Pure slop—yet better than the SI headline.

Strout quotes extensively from the BTC camp and, in a pattern of unknowingly punching herself in the crotch that you’ll see persisting throughout these stories, compared Houlihan’s case to those that turned out differently without any effort to relate them. She may as well say “This guy was convicted of murder, but others in similar cases were found not guilty” and leave it at that, as if the reader is to divine innocence from this haphazard gurgling alone. While it’s possible that Strout genuinely fails to understand that not all “tainted meat” cases (and it’s a near-ubiquitous excuse) are alike, it’s more likely that she’s bringing up Wilson and Martinez to intentionally muddy the picture.

Typical, wholly expected, and shameful. It’s basically a recitation of Houlihan’s defense and the blather of her lawyer.In her Runner’s World story, editor-in-chief Sarah Lorge Butler clears the low bar of striving for greater objectivity than Chavez or Strout, but it’s still a bad, melancholia-and-pathos-driven piece (this wistful style is a reason I often enjoy Lorge Butler’s work). It suffers indelibly from this: “The level of nandrolone found in her test was extremely low, Greene said, so low that it became impossible to distinguish where it came from.”

Sure, Greene said that, but 5 nanograms per milliliter—a value the Letsrun story I linked to above included—is far from low. If you wade through this WADA technical document, you’ll find that—assuming I can read—that any test showing >15 ng/mL is automatically deemed an “adverse finding” (i.e., a doping “positive”), whereas anything over 1 ng/mL triggers further investigation. If the level is >2.5 mg/mL and the source is determined to be exogenous, it’s again an “adverse finding.”

While it’s possible for an athlete to show absolutely stratospheric levels of this drug and many other PEDs, this fails to negate the fact that Houlihan’s result put her well beyond the edge of culpability. If Stewie drives with a blood-alcohol level of 0.30 while Brian hits the road at “only” half of that, Brian is still legally drunk.Alison Wade demonstrated unintentionally splendid comic timing with this snippet from her June 7 Fast Women newsletter:

I think what Wade was really saying here is that she’s aware doping is endemic and can claim the career of any runner at any time, and that she chooses to simply ignore this because otherwise she might be tempted to do something different with her free time. I doubted when I saw this that there was any athlete whose conviction would prove sensational enough to cause her to lose her faith (Rita Jeptoo wasn’t enough?), because deep down, like me, she doesn’t really have any; she plows on anyway because writing about running, the way she wants to, is her thing.

God showed up almost immediately to put Wade’s alleged faith to the test. Here was perhaps the highest-profile U.S. woman runner imaginable, one who had shown shocking improvement followed by mysterious invisibility, entering the news cycle as someone whose doping case was already closed. So what does Wade do? Obfuscate, finger-waggle, and deny.The main factor to consider is that anyone this apparently incapable of thinking clearly, or demonstrating this florid an absence of objectivity, shouldn’t be regarded as an authority on running or anything. This is nothing more than flinging poo at the walls of a cage, with the enclosure in this case being simple reality. I advise joining it; we’re* less dickish than we look from the other side, once you open your mind.

Of course, none of these characters care enough about judgments like mine to change a thing. Their concerns about truth are completely displaced by a fierce yearning for approval and an infantile urge to make bad things in life disappear by being sufficiently indignant. They must be even more fun than me at parties—where, I humbly admit, I’m invariably what keeps the collective freak-machine roaring along.The Washington Post found someone passed out in a janitorial closet to write a fantastically ignorant piece about the matter, supplying unquestionably the funniest of Houlihan’s lawyer’s lies: “It [nandrolone] is not a substance any runner would take.” His job is to lie, but he can’t be this stupid. I’ll leave it to the reader to investigate doping cases involving runners testing positive for nandrolone.

Lindsay Crouse has already begun braying stupidities in her charmless, brainless way, but until she excretes a bad New York Times story about it, referring to her own past, equally terrible work throughout, I will leave her and her incessantly off-base, almost randomly generated tweets alone.

Mario Fraioli didn’t have time for a story per se, as he puts out his extensive newsletter on Tuesday mornings. But he nevertheless had time to think like a journalist and start asking good questions.

Even if you’re convinced Houlihan was wronged, these are the kinds of questions you should be seeking answers to. But no one will pay attention to Fraioli; they’ll just nod at how thoughtful he is about difficult issues, then return to cyberwanking over what the squawky types are dispensing.

That seems like a solid enough start.

In addition to the double standards I’ve already highlighted, bear in mind that many of these observers maintain an ongoing, at times even hysterical, distrust of Nike as well as male coaches of female talent. These things ruined Mary Cain, after all. It’s almost amazing to watch them simultaneously suspend this distrust when a Nike athlete they revere—or more to the point, one they fear criticizing even when they have the greenest of lights to do so—does exactly what they scream Nike types are inherently guilty of, and turns out to be a cheater.

Jerry Schumacher is as popular as a white man can be among the Wokish harpies, and Shalane Flanagan is among the other BTC coaches. And none of the cowards like Chavez, Wade and Strout will dare question the wall of BTC support that’s been thrown up—as if this is not exactly Nike’s intent. The BTC camp has had a lot of time to think about this, not just the excuse but how to ram it up the public’s ass and gaslight us all once more into acceptance. I’m betting they knew that, for all the “Nike ruins women” polemics from the Lindsay Crouse gang (though to be fair, while running is rife with dingbats who think Crouse is an editorial tour de force, I doubt any would agree to be her gang members), a sufficient cry of “no fair!” would be enough to bend meek, approval-dependent fanboys posing as legitimate story-seekers like Chavez to their needs.

Again, my point isn’t that Houlihan’s story can’t and won’t turn out to be true in the end. It’s the shameless and breathtaking hypocrisy from the Wokish. And it also, again, makes me wonder if the questions a real journalist would ask occur to them at all. Are they curious, for example, about the huge differences between previously overturned doping tests and Houlihan’s? Do they know the difference between “trace amounts” of something and five times the normal upper serum level of that substance? Do they know the difference between the possibility of small amounts of something entering the bloodstream from ingested food and amounts that could never be achieved by eating the substance claimed? Does it strike anyone as fishy that Houlihan had the bad luck to eat that ill-chosen burrito containing essentially the one thing that could have created an inadvertent nandrolone positive at exactly the time it would have done so? Are these pundits aware that the case—and I’ll say it again—is over, and that in quoting Houlihan’s lawyer, they’re therefore hanging their own case on the words of someone who already lost the same one despite being paid handsomely to win precisely such cases?

This post is shy of links I would ordinarily use to support my points; I may add some later to the Web version of this post, but I wanted to get it out as quickly in the aftermath of the initial wave of “Just because it’s settled doesn’t mean it’s settled” articles and Twitter takes. I’m curious if any of the outraged pundits mentioned above will mitigate, walk back or otherwise amend their stances as more information—which is not going to prove helpful to Houlihan, I suspect—from the case files becomes available. Maybe someone will contrast the specifics of the case with others they’ve already improperly likened them to. I already know who won’t for sure, but I have a few tepid “maybes” in mind. But they’re very tepid. At this point, if athletes can’t be trusted to remain free of mistakes, why should the people whose literal and psychological livelihoods depend on relaxed relationships with all of running’s principals?

One last thing, a sidebar really, about Houlihan’s suspension and the strong likelihood that she doped on purpose. I don’t really follow pro running in the way I once did, and my passion for high-school running isn’t accidental or a mere consequence of excessive hometown nostalgia. It’s mostly so I don’t have to routinely confront any of this misery.

The deal is, I stopped worrying about who was doping a while ago because when someone commits to a world-class group like the BTC, it's known among all parties that they are training to compete at the highest levels against the rest of the world's fastest dopers. All other countries see the game the same way, and recognize the U.S. as at least as big a cheat as any other country. So who in their right mind really expects any club to win big and host exclusively clean athletes? It doesn't even really make sense.

So how is it not built in that people's heroes—and this being a small sport, in some cases their friends, or at least the recipients of their swashbuckling adulation—occasionally get popped?

Maybe if I were a 13:20-13:30 guy just out of college, I would aim keep a contract to run for four years or so, take a couple cracks at the Olympic Trials, and in general live the dream (I’m not being facetious) while knowing that 13:20 against an army of drug-soaked Africans is basically racewalking. There would be no reason take drugs even were I so inclined, because they probably still wouldn't make me a 12:50 guy even if I evaded the testers or their tests. But if I loved running and racing for its own sake enough, I could treat it like a short, well-paying-enough career and then move on to recreational road-racing or full-time couch-surfing at 28 or whatever. And I believe that a number of pros at any time more or less fit this description.

Perhaps paradoxically, I don't judge Houlihan that harshly, in context. And I believe her competitive drive and love of the sport are both genuine—but these things became really fraught when you happen to be really, really good. My views on the ethics here are sort of complex and worth a post on their own. I see guys my age getting testosterone at “anti-aging clinics” to better their chances at running 18:00 5Ks as far more pathetic than dopers with incentives beyond the parochially egomaniacal.