Did Kip Keino hand Marty Liquori the 1,500-meter win at the 1970 MLK Games?

Some are more cheerful about the idea than others

On May 16, 1970, reigning Olympic 1,500-meter champion Kip Keino of Kenya traveled to Villanova University outside Philadelphia to face American Marty Liquori, then running for the Wildcats, in a metric-mile contest at the Martin Luther King Jr. International Freedom Games. Three years earlier, Liquori had become the third American schoolboy to break four minutes for the mile, and the third in four years. (Bear in mind that 1967 was also only thirteen years after the first sub-four mile by anyone.) At 19, Liquori had himself reached the 1968 Olympic 1,500-meter final, becoming the youngest athlete ever to do so and finishing 12th.

Perhaps because of the approaching national holiday, this 1,500-meter race has recently become a topic of e-mail discussion among some of the sport’s pre-eminent Boomers. You can read a ten-year old account of the contest by a then-12-year-old eyewitness here as well as this New York Times recap. But I recommend first watching the race video.

As the post on Villanova Running notes, Keino got to halfway in 1:56.6, which is 3:38.6 pace. This was on a cinder track, and at a time when the world record was Jim Ryun’s three-year-old 3:33.1. You can also see in the video that Keino achieved this split with erratic pacing, making his frontrunning effort incrementally more taxing. Among those who believe that Keino rigged rather than quit, these facts summarize their main argument.

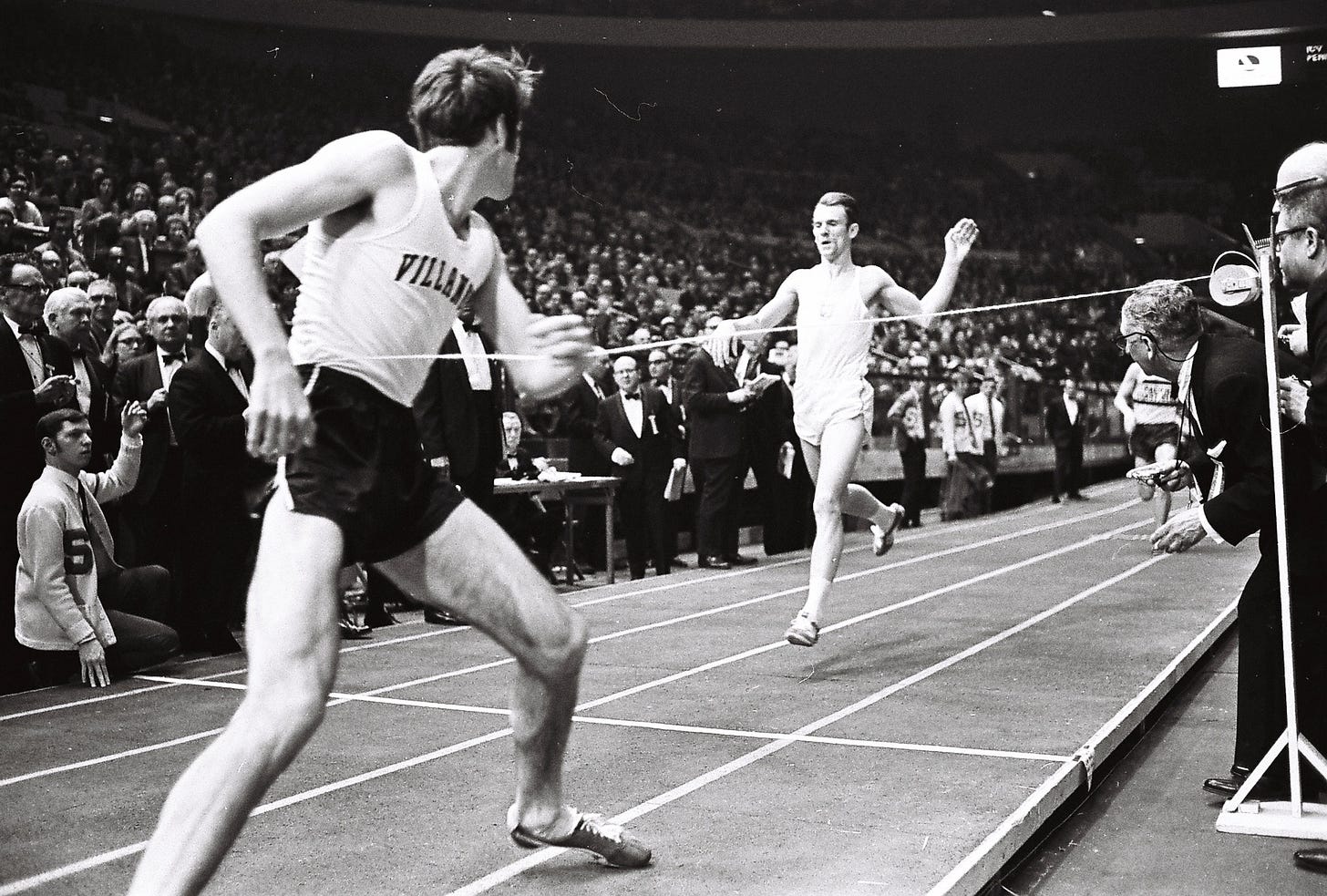

Jeff Johnson took the photo below, which shows Keino beaming at Liquori while practically jogging down the homestretch almost in lane 2. Liquori had shouted, “Don’t quit, dammit!” a moment before, perhaps already frustrated that the win he was obviously about the secure would be delegitimized by the Kenyan’s ostentatiously jovial transition into a “just happy to be here” type of footracer in the race’s closing moments.

Johnson offers this account of the race:

My recollection is that in Keino’s mind it would be some kind of an “insult” to America for him, a black African, to beat an American in a track meet (the Martin Luther King Games) honoring a black American hero. Keino had a huge lead over Liquori in the race, and there is no doubt in my mind that Keino just shut it down. He wasn’t breaking down. In my picture, Keino is grinning at Liquori, which infuriated Marty, who felt humiliated by Keino’s handing him the victory. In fact, I think Keino is in lane 2, having moved wide so Marty could take the lead more easily.

Liquori himself challenges this account:

To the theory about Kieno. Wrong.

The Villanova track first lane had 3 inches of lose cinders. Maybe the worst track ever that Kieno ran on. His overly optimistic pace in the first two laps caught up with him. His reaction, I was to learn later, from remarks by Ron Clarke, was a repeat of other instances when he knew the race was lost. Again I knew ahead of time he might pull that and that’s where “Don’t quit dammit “came from.

The two have another entertaining difference of opinion about an event captured—almost—in another of Johnson’s favorite finish-line photos. Actually, two photos.

Johnson’s recollections:

In 1970, I think it was, in an indoor meet at [Madison Square Garden], Marty was blatantly and repeatedly fouled by the Polish miler, Henryk Szordykowski. Marty finally got the lead off the last turn, crossed the finish line, planted his foot and spun around launching a punch at Henryk (that missed, thankfully, because it would probably have broken his face and Marty’s hand). I’ve got a really good shot of that, too. Marty was always good for my photography. The shot of him beating Jim Ryun in the 1969 NCAA Champs is, I think, the best photo I ever took. It also was historic, in that it marked the changing of the guard in American miling.

Liquori disputes this as well.

I knew before the race that [Swordokowski’s] Tactic was to cut in sharply on the leader with one lap to go forcing the leader to break stride.

Then (it) was Swordokowskis race because he was fast on the last lap. I knew this because. He had done it to Frank Murphy the week before and Frank warned me.

So I was ready for it and pushed him out to the second lane a little too hard. I was disqualified but later reinstated after review. I don’t know if they had (video footage) in those days.

I don’t know what the history of running in the 70 would be without Geoff’s presence. But in the photo of Swardy you can see that I am pointing my finger at him. There was no punch thrown. I’ve never thrown a punch in my life on any occasion.

I love this. I was 150 days old when the 1970 MLK Games were held. Marty Liquori is probably as fired up today about the insinuation that he “didn’t really beat” Kipchoge Keino on his home track as he was almost 52 years ago. And he’ll be equally annoyed every time someone brings it up until no one is still alive who can confirm for certain that the race even occurred.

Obviously, two divergent but non-contradictory things could have happened: Keino could have tired himself out so much with his playful early pacing that he couldn’t have produced his usual kick, but he still could have held off Liquori and everyone else with relative ease.

This, in my opinion, is what did happen. And it only delegitimizes Liquori’s win if Liquori himself decides it does. Whether someone’s name is above yours or below it in the listed results of a race, it doesn’t matter what their state of mind during that race was. But Liquori, like many great milers, has a sufficiently robust ego that he not only needs to feel like a winner, but like a winner who couldn’t have lost any of the races he won no matter what others did.

It’s impossible to mention Marty Liquori without mentioning the 1971 “Dream Mile,” which also took place at the MLK Freedom Games. In ‘71, the meet had been moved about fifteen miles southeast to Franklin Field. The race lived up to its hype, the level of which reportedly exceeded that of any non-championship 1,500 meters or mile race since perhaps the “Miracle Mile” duel between Roger Bannister and John Landy in 1954.

Liquori was a beast on the track, and like most successful milers knew how to use his elbows like Dikembe Mutombo. I also think Keino could have cleaned his clock that day and simply decided not to. I think Liquori wants to believe that he would have run down Keino given a supreme effort by both men down the home straight, and I think he doubts this now as much as he did on the day.

Who cares? He won fair and square. The fact that he was probably allowed to by a superior competitor shouldn’t chafe him. Not that much. Every race I ever won myself was owed to a combination of generosity, genial lassitude, and gutlessness from others, and I couldn’t be more grateful to each of those men and women today.