Ecotone Peaks

Human bonds become lasting and inseparable not as the result of the noblest conscious decisions, but from negotiating with the quasi-deterministic aspects of our unique spirits and personalities

The turn of the century saw the American cable entertainment network Home Box Office (HBO) release three drama series that each captivated viewers in emotionally penetrating ways that had never been explored on television. All three are now on most “official” top-ten lists of the best programs ever produced.

In 1999, The Sopranos began a seven-season run that melded predictable The Godfather-style ethics and gore with revealing, darkly comedic psychological subplots at times evocative of Frasier Crane. In 2002 came the first of five seasons of The Wire. This, all in all, is the best television series I’ve ever watched—I didn’t see it until 2019—and featured the most complex and unforgettable vigilante in the history of the medium in Omar Little, portrayed by Michael K. Williams. In between came Six Feet Under, which premiered in the spring of 2001.

I didn’t have HBO when Six Feet Under premiered, and after the first of its five seasons, a friend presented me with a set of videocassette tapes containing its thirteen episodes. (As a reward, she would later be invited to appear on the show Jeopardy!, although only for one episode.) But although I liked what I saw a great deal and managed to catch seasons two and three in something like real time, I didn’t finish watching the entire series until this week.

While each of these three series broke ground by exploring everyday yet long-forbidden topics—steamy sex scenes involving male couples, closeted gay mobsters and church deacons, even sibling incest—they also adroitly stuck to a formula that is reliable but difficult to execute onscreen without stumbling into the strictly maudlin: people finding hilarity and even joy in the darker aspects of personal karma and its staunch inevitabilities, most of which engender more chaos and love than they do comfort and ennui. Many people are constructed to prefer the first of these combinations whether they recognize this or not.

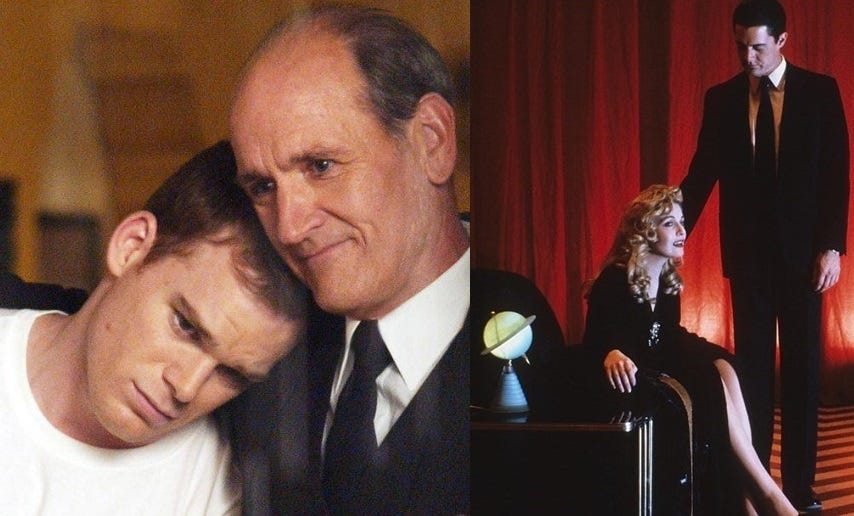

The first television series I ever became obsessed with was ABC’s Twin Peaks. Although the show made an unexpected impact when it was released in 1990—it was unclear whether the often-inscrutable vision of David Lynch could be translated into a wide and loyal prime-time viewing audience—it only ran for two seasons, and for most people initially enchanted with it, Twin Peaks was a come-and-go phenomenon. Still, in 2016, Rolling Stone ranked the show #17 on its list of the best 100 television series ever made.

I didn’t watch Twin Peaks until 1992, shortly before I graduated from college and also on videocassette tapes (albeit not bootleg copies). I’ve probably watched all two-dozen-plus episodes a dozen times over the years, mostly in the 1990s. When the Internet became a thing in the middle of that decade, the first message-board-style sites weren’t running-related boards. They were sites like Alt.TV.TwinPeaks, the digital strands of which can still be unearthed today. I even bought the sheet music for some of the series’ songs from someone in Montana before there was eBay. I sent him a check for around twelve bucks, and he sent me the goods.

The show centered around the murder of a high-school girl named Laura Palmer, played by Sheryl Lee. Palmer was newly dead at the opening of the pilot episode, and Lee’s primary role was actually that of Laura’s cousin Maddie. She wasn’t one of the more memorable cast members, and Lee is not an actress with superior range. Still, she was essential to a show that allowed me to spend a great deal of time in states of greatly exaggerated and arguably unaccountable enjoyment.

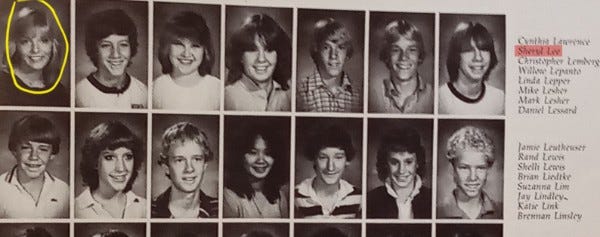

I was nosing idly through a long-neglected bookcase at Lize’s house the other day and came across her sophomore-class yearbook from Fairview High School. I remembered this as the year in which Lize won the first of her three individual state cross-country championships, and I went hunting to see what the yearbook editors had pitched on this front. Not much, as they had no idea what they were dealing with.

But I did make another discovery.

I had learned at some point soon after meeting Lize in 2009 that she and Lee had been classmates. But Lize never remembers seeing the future actress, who was probably busy as a teenager doing her schooling away from school like a lot of budding actresses, and I put this coincidence out of my mind, even when the so-so-but-watchable reboot of Twin Peaks was released by Showtime in 2017.

Still, this was an entertaining interlude. And it came as I was closing in on the final episodes of the final season of Six Feet Under, with which Twin Peaks shares elements of surrealism and the inescapability of the unseen forces that guide human interactions and events, some of which are so confusing and irresolvable that human minds have no choice but to call them “supernatural” and erect baroque mythological superstructures around this unresolvable angst to help process its overwhelming reality. The unamended results can often be beautiful.

At the end of the third-to-last episode of Six Feet Under, “Ecotone,” the show’s nominal quixotic rascal of a main character, Nate Fisher (played by Peter Krause) dies in the hospital of a more-or-less-direct result of a congenital brain aneurysm bursting during an illicit sexual affair with the sister of his deceased wife. This affair took place while Nate’s current wife, a mostly genial edge-case sociopath with her own history of florid sexual profligacies, was seven and a half months pregnant with Nate’s child.

In his last lucid moment, shortly after awakening from a brief coma, Nate looks over at his wife and tells her he doesn’t want to be with her anymore. He tells her this with a combination of exhausted resignation and sneering defiance. Their love was at best complicated and fraught, but it was real enough to sustain for the entire series the illusion it could survive in a healthy way provided Nate himself did. Nate’s final act was not intended to punish his wife but to admit to the cosmos that at least he understood that he was himself all along.

That was the first gut-punch. Because I’m now in the era of no-tapes binge-watching, Nate’s death scene and the show’s final two episodes blended functionally into one long series finale. The second gut-punch was the very end of the final episode, which shows the lives of the characters spooling forward across the decades from 2005 until their inevitable ends, most of these natural, one violent and tragic, one extending to 102 years.

The lives of the main characters remain intertwined despite the adulterous and drunken tumult and apocalyptic tirades characterizing their relationships throughout their five years of fucking, crying, brawling, pretending and mending that were chronicled during the show’s run. Most of them found what they required and wanted in each other not because they settled for each other, but because they were meant for each other. No one else could have put up with everyone else’s bullshit and still laughed and cried and worried and loved enough to make it all worth it.

There is no hint whatsoever in this extended scene depicting family functions, the training of adopted sons for the family business, and bedside saying-goodbye scenes of showrunner Alan Ball trying to offer emotional succor to his viewers. This is not a romanticizing of the ugly or the painful or a suggestion that people sometimes just muddle through life more or less happy in spite of making knowingly suboptimal choices. It is a stark presentation of how life and its always-wrenching family, romantic and other intimate relationships really are. Most of the lasting bonds any of us wind up forming are unavoidable and hard to break even with dedicated, reckless effort.

Whatever one makes of karma, anyone who looks back on the patterns of their own relationships is likely to conclude that is the essence of who we are more than our individual actions that create the strongest and most lasting bonds, strands and lattices that refuse to break until the inevitability of death relegates one more ingredient in the grand recipe of life to a dispersed set of memories, none the same, all pure and real.

And these relationships don’t have to be human. According to the Internet, an ecotone is “a transition area between two biological communities.” I often have wondered what I was doing on March 12, 2014, at the moment Rosie was born. I am pretty sure I was not having a good spring. While I was meandering non-linearly toward sobering up two and a half years later, Rosie was off in a different part of the country growing from the amazingly beautiful puppy she must have been into the young dog she was when our paths crossed on June 30, 2018 at the Humane Society of Boulder Valley. Something took her back to Boulder at just the time I was looking for a dog, and someone I knew who was volunteering at the HSBV had her eye on a newly arrived and very special one. It is now almost impossible for me to imagine what the last five and a half years of my life would have been like without Rosie in it, but why bother? She was always on her way here anyway.

It can't last forever, but it will be forever for at least one of us. The pictures I have of Rosie and others are great, but that's not what any of it is about. As Nate Fisher’s ghost tells his younger sister as she prepares to take a photo of her remaining family members before setting off alone from Los Angeles to New York, “You can’t take a picture of this. It’s already gone.” But “Nate” says this with a warm and brotherly smile, because what he means is that the most important things in any of our lives can’t be reduced to images.

That kind of love and meaning is enough weight to carry through one lifetime. It might as well last an eternity. The most vital and memorable people and situations we ever know or experience never really “end” any more than they could have been consciously staved off in the first place. Williams died of a poly-drug overdose in 2021, and his character Omar was shot in the back of the head by a child in a West Baltimore convenience store. Williams is missed by his family and millions of fans worldwide, but thanks to his talents, a man who was never alive at all and died violently onscreen will survive and affect others for as long as civilization itself persists as any kind of interconnected sets of lattices and junctions.