How many other NCAA records will Katelyn Tuohy break?

Runners this talented have a murky future, in a good way

Katelyn Tuohy is only 20, but seems to have been a major figure in distance running for at least a decade. It’s really only been about six years since Tuohy’s results first started pinging running’s stat-hounds, and about five since The New York Times either published a refreshingly transparent profile of Team Tuohy’s longer view or tried to ruin her career, depending on whether you were observing mostly as a knowledgeable sports fan or mostly as a pseudo-feminist scold masquerading as one.

Although Tuohy broke five minutes for the mile indoors as a seventh-grader in 2015 and was among the best girls in New York State as a middle-schooler, she first made national-level waves in the spring of 2017. That season, as a freshman, she ran 4:18 for 1,500 meters (about 4:49 for a full mile) at North Rockland High School, which sits forty-five minutes north of the Bronx and near the widest point of the Hudson River.

Tuohy became a genuine cross-country legend in that fall, maybe the best schoolgirl on turf in American history. Everything about her was smiles (real ones) and everything about her was justifiably sensational. From the start of her sophomore year onward, she went undefeated in cross-country and lost sparingly on the track (and never at anything longer than a mile). Losing no momentum, Tuohy unspooled an indoor sophomore campaign that brought one unprecedented prep-level result—a 15:37.12 for 5,000 meters, breaking Mary Cain’s national all-conditions high-school record by over eight seconds and setting a U.S. Junior (U20) record—and a few other great ones, among them a 9:05.26 for 3,000 meters.

In chronicling Tuohy’s éclat and ascendancy in that NYT profile, Matthew Futterman followed up a verboten observation with an off-limits question:

the real challenge for Tuohy is solving one of the cruelest puzzles of youth sports: Why do so many gifted teenage female distance runners fizzle out by their early 20s, unable to capture the speed of their youth?

Like many topics Wokish women hold dear, they want the unique ways female anatomy and physiology intersect with performance to be fervently discussed, but they want to control exactly who raises the topic and how. Alison Wade of Fast Women has often mentioned the desirability of “pumping stations” at marathons and the need to openly discuss menstrual periods, but God forbid a man delve into this topic. (One woman even tweeted at Futterman, “The fact that you, a man, wrote this article only heightens the male voyeurism of young women's changing bodies.”)

And because even the version of Lauren Fleshman who was five years from fully unraveling already knew the answers to everything and who was allowed to supply them, she was happy to blare from the etchings on her sacred tablets.

It’s funny that Fleshman approves of any pressure on a 17-year-old whose talent has “prematurely” landed her on the Olympic stage, but not a 17-year-old girl with a 5K PR one minute slower at the same stage of sociological development. But who knows what she’d say now—she’s really lost her mind.

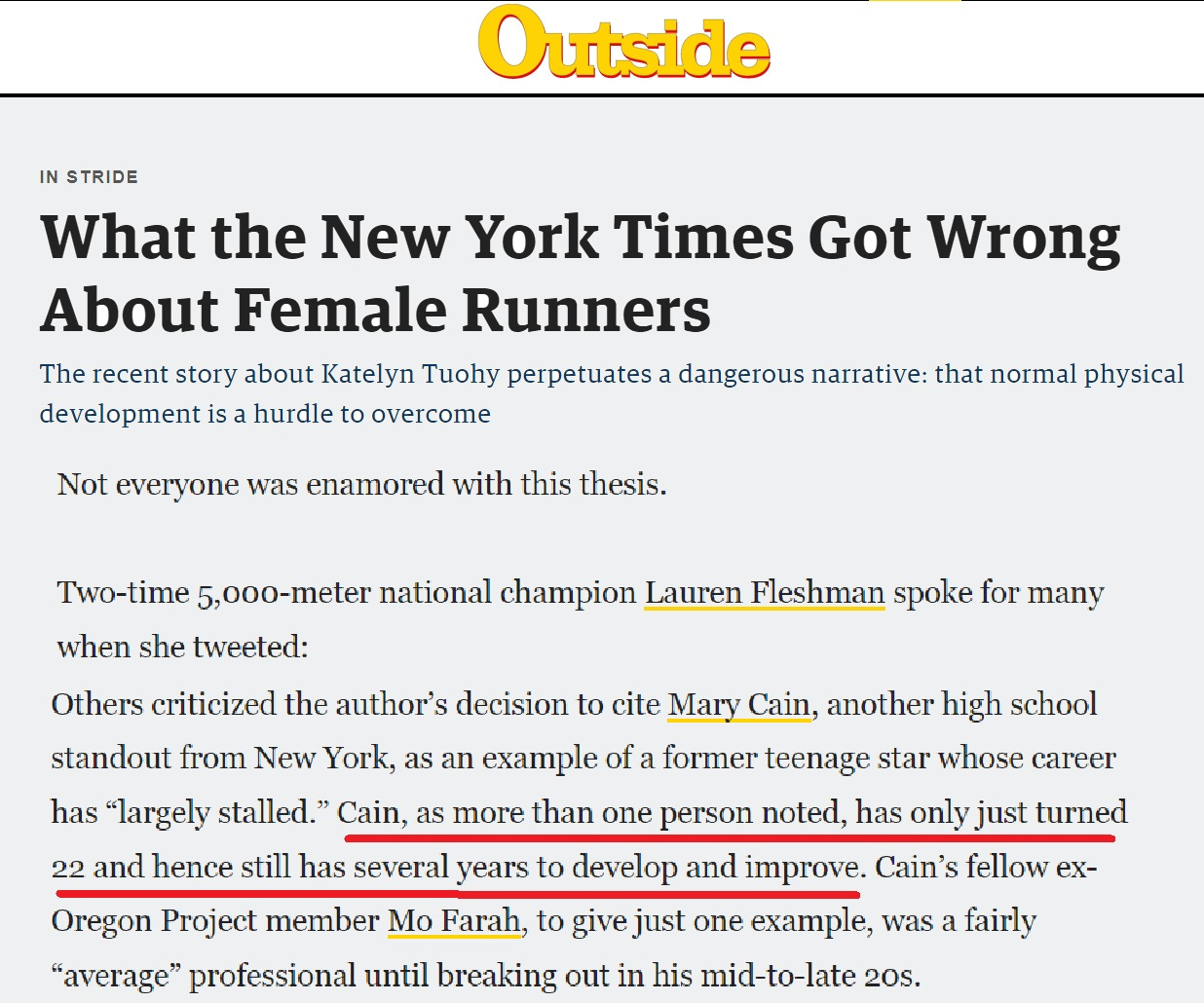

Others responded in media outlets. "The story told about Katelyn Tuohy is unrealistic," according to Elizabeth Carey, who continues to this day demeaning overly ambitious young women by projecting her untoward experiences onto them under the aegis of stopping abusive coaching. And Outside Online’s designated needler, Martin Fritz Huber, struck again with another Pulitzer-worthy "The Interwebs are displeased" piece, claiming (as did others) that it was premature to suggest that Mary Cain had passed her career zenith and agreeing with the "Shut up about puberty" crowd.

The media coverage of the inimical Mary Cain-Nike Oregon Project separation would not reach its late-2019 apex for nearly another two years, but her career stalling was probably the driver of three-fourths of the “Don’t you DARE, sir!” pushback. But not all of it. In this century, running fans watched a teenage sub-2:40 marathoner blog for years about how much she loved it all before quitting the sport as soon as she reached college, and also saw various other young starlets not fulfill their promise as 12-year-olds. Until a couple years ago, Wade was part of a loud chorus that, like Fleshman, basically told anyone talking about a young female runner’s exploits and potential to can it, even while publicizing the exploits themselves.

Although Tuohy didn’t lose a race in her last three years of high-school cross-country, she had begun to look beatable, and her times weren’t improving. She was so good already that if she merely held the same level for four more years, she’d be a varsity runner on any top-five-in-the-NCAA team. But wouldn’t it be a bummer if the developmental dice had indeed fallen unfavorably, and the fast and ebullient Katelyn Tuohy would get no faster?

Because Tuohy’s senior spring coincided with covid restrictions and she suffered an unspecified knee injury over the summer, her transition from high school to college at North Carolina State University involved an unusually long spate of not racing. Owing to the fall 2020 NCAA National Cross-Country Championships being run in March of 2021, Tuohy became a 2020 All-American in that sport with a 24th-place finish after she had already made her collegiate debut in 2021 with some lukewarm indoor races.

As a freshman outdoors in 2021, Tuohy ran 4:12 for 1,500 meters and 15:47 for 5,000 meters—creditable, but not quite the force she had been. She seemed to have made the transition to the NCAA well, but she hadn’t done anything no one expected her to do. In her first full collegiate cross-country season that fall, she was second in her regional meet and 15th at Nationals, and she and her Wolfpack teammates—second to Brigham Young University in “2020” in a race actually held only eight months earlier—flipped the script on the Cougars and won the team title by 38 points. Tuohy was still amid plenty of success.

Tuohy’s sophomore-year indoor season recapitulated her breakout display as a high-school sophomore. She ran 8:54.17 for 3,000 meters and 15:30.63 for 5,000 meters; those were both personal bests, but she also proved she was a championship contender at the collegiate level by taking second in both races at the NCAA Indoor National Championships. Outdoors, she got even better—and she got quick. She lowered her 5,000-meter best to 15:14.61 and also blitzed a 4:06.84 1,500 meters en route to winning her first individual NCAA title in the longer event at Outdoor Nationals.

Tuohy’s recently completed third season of NCAA cross-country is easy to summarize: Five races, five wins, an individual title, and another team crown for NCSU. Two weeks later, as many distance runners now do before taking any real pre-indoor-season break, Tuohy raced the 5,000 meters at the Boston University Season Opener, running 15:15.93 and placing second to a professional runner.

Last weekend, Tuohy placed third in the mile at the Dr. Sander Invitational in New York City in 4:24.26, breaking Jennifer Simpson Barringer Simpson’s 14-year-old NCAA record by 1.65 seconds. That’s worth about 4:04.7 for 1,500 meters (full meet results).

In less than two weeks, Tuohy will run the 3,000 meters at the Millrose Games, also at the Armory in New York. The NCAA record is 8:41.60, held by Karissa Schweizer. What are Tuohy’s chances of breaking it?

Below are Tuohy’s best performances on the track per World Athletics quality points (the top two come from the same race, where official 1,500-meter splits were taken).

Tuohy should be able to perform at the same level or better in the 3,000 meters as she just did in the mile. Scoring 1,190 points will require an 8:42.16, while breaking Schweizer’s mark by 1/100th of a second would demand 1,192-point output.

I think Tuohy has a better shot at the indoor (and overall) 5,000-meter NCAA record of 15:01.70, also set in 2009 by Simpson. This isn’t because 1,190 points in that event is worth 14:58.99 (and 14:46.42 outdoors). It’s because she clearly loves running fast indoors, and seems to especially enjoy the 5,000 meters. The only issue is that Tuohy probably won’t get a chance to run a fast 25-lapper in the 2023 indoor season. with championship season coming not long after Millrose.

Although Tuohy is in her third year and hasn’t redshirted at all, she’s considered a sophomore for eligibility purposes owing to NCAA athletes being granted an extra year thanks to the covid stuff. That means she could have three remaining outdoor seasons to go with two more cross-country and indoor seasons, unless my understanding of the eligibility addition is wrong. Thanks to recent changes to NCAA student-athlete rules, she already has a professional deal with adidas, which might incentivize her to not turn fully professional before 2025 (the team she’s on should be great through then).

If she stays healthy and completes the NCAA 2024 outdoor track season, by which time she may be thinking about qualifying for the Olympic Games, Tuohy will probably have run close to 4:00, 4:20, 8:35, and 14:45 and own the outdoor 1,500-meter, indoor mile, and outdoor and indoor 3,000- and 5,000-meter records. If she doesn’t grab all of them, it will only be for lack of opportunity.

The same people, by the way, who as recently as 2020 or later were claiming that hyping phenomenal teenage girls is uniquely destructive have nonchalantly joined the ranks of the hypers, and now cheer on anything and everything remarkable that high-school girls do. Since these people frequently critique the coaching profession, it would be instructive to learn what caused them to relent, other than finding themselves the only ones still banging away at the warning gong.

I think this former girl-boss is already the woman athlete everyone hoped she would become. And let’s* hope the show continues unabated, because Tuohy really is delightful to watch.

References: