It's pretty easy to determine where you stand as a distance runner

When someone claims to be a pro athlete, how far from the world-record level can they be before laughter becomes the primary response?

Yesterday was the eighteenth anniversary of my one and only ultramarathon finish, a second place at a 50K on modestly rolling golf-cart paths in Peachtree City, Georgia. I posted my real-time write-up of the experience on my Blogspot blog in 2016, and it was imported to Substack when I made the switch to this place in the summer of 2020.

One of the main reasons I entered the race despite being in questionable shape was having not finished the only previous ultra I had entered, also a 50K national road championship (the version held two and a half years earlier in Pittsburgh). I probably would have run regardless, though, because I had moved away from New Hampshire between early 2002 and late 2004, and the race in Georgia would offer a chance for me to reunite with some Central Mass Striders clubmates.

Despite my getting second place in a USATF National Championship, averaging 5:59.91 minutes per mile for a little over three hours didn’t represent anything close to my best effort. According to the IAAF, my 2:24:17 marathon, which I ran in 2001 in a race in which I lost maybe a minute to a series of attempted and committed port-a-john stops, ranks as my best, even though it’s not better to me (and per other conversion tables) than 51:32 for ten miles on a non-gimme course.

Although I really shouldn’t count a time at Boston as a personal best since it’s an aided course, I’ll justify this by observing that there was a negligible net headwind that day (1 MPH, according to the BAA website) and that Boston times tend to be non-spectacular in neutral-wind years. (The fact that I had to stop to take a dump is baked into the distance of the event. I can speculate all day about how much faster I might have run otherwise, but that goes as far as “What if I’d had better shoes?” Lots of people faster than me have defecated—sometimes explosively and without producing well-formed turds—during personal-best marathon runs.)

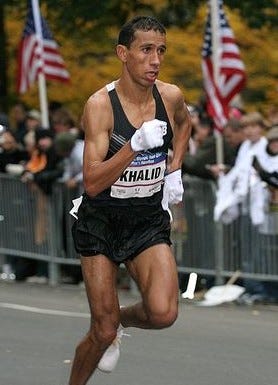

But if I treat that 2:24:17 as my best lifetime performance, it means that I was about 15 percent slower than the best distance runner in the world at the time. In 1999, Khalid Khannouchi, then a Brooklyn-based Moroccan dishwasher, set a world record of 2:05:42. 2:24:17 is 14.78 percent slower than that.

(Khannouchi would become an American citizen in the spring of 2000, break the American record that fall in 2:07:01, and then break his own world record in 2002 by four seconds. Khannouchi—who still holds the American record, a fact I’m convinced is lost on at least two-thirds of supposedly hardcore running fans—ran all these of these records at the Chicago Marathon.)

This shows that you can be a decent club-level runner known only to local yokels and still be barely within 15 percent of the best in the world in terms of raw output. At the same time, far fewer than 1 percent of all male marathon finishers will ever run 2:24 or even 2:30; it’s probably less than a tenth of that, i.e., fewer than one in a thousand.

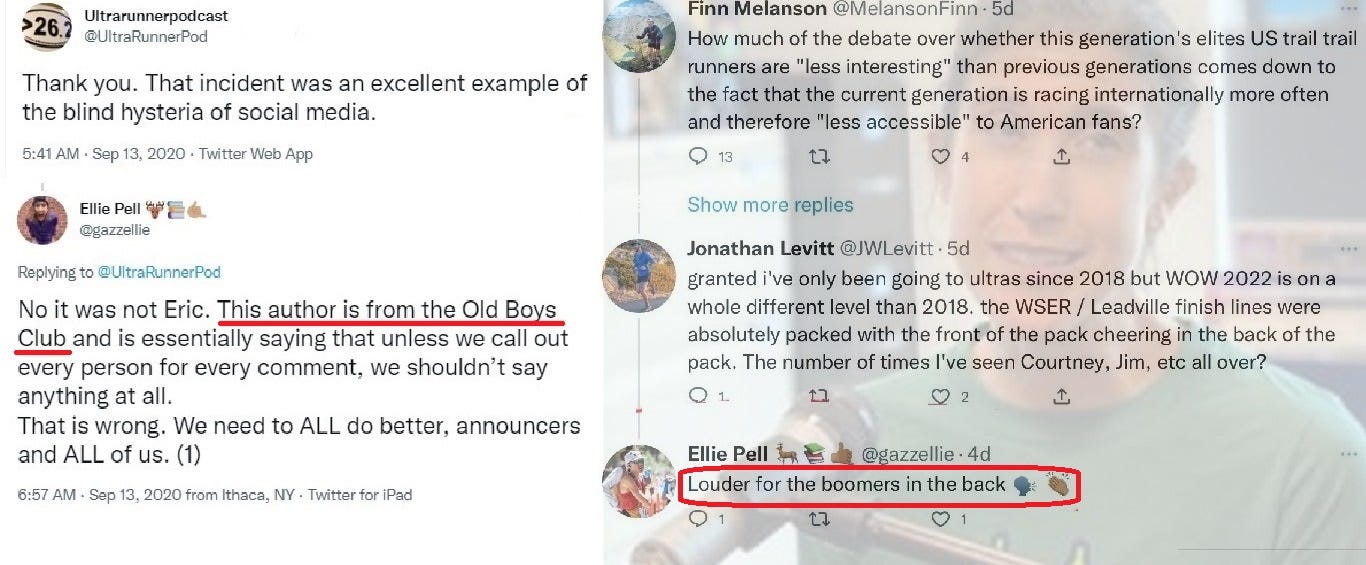

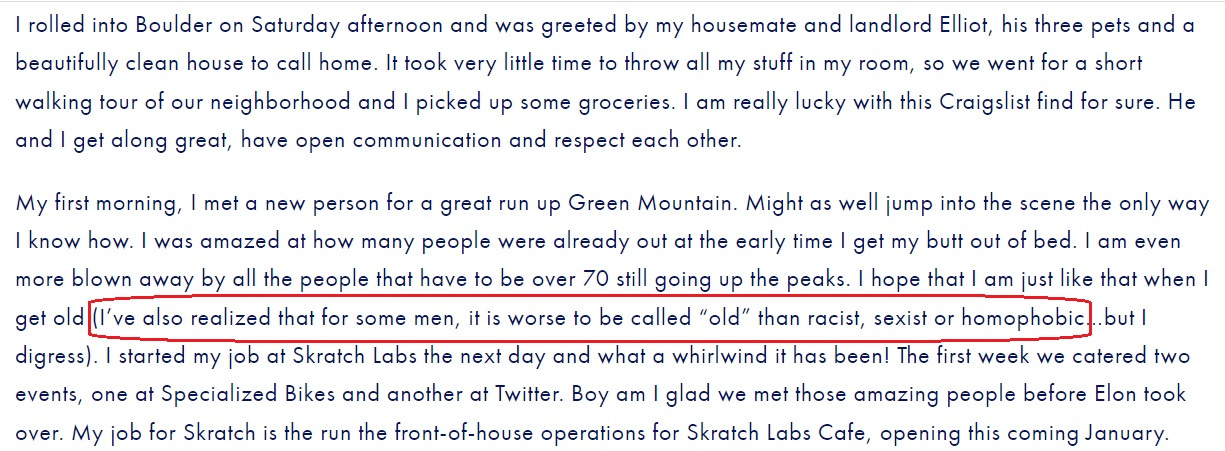

While a decent runner can, however, easily construct a case for being better than he or she is, it’s far easier to knock these cases down than it is to build them. In the interest of continuing to swipe at the lowest of low-hanging fruit, here’s an example of someone who, despite recently writing about moving to Boulder to take a full-time food-service job, labels herself a professional athlete.

Ellie Gazzellie is explicitly not making a living as an athlete, so her bio includes a lie as well as an apparent joke. But she’s a solid runner, with a spate of impressive finishes in ultras. She’s also run a few road marathons, with a personal best of 2:41:52, good enough to qualify her for the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials, where she finished in the top half of the field. (A 2:37:00 or better is now required to qualify for the Trials.)

2:41:52 is 20.74 percent slower than Brigid Koskei’s world record of 2:14:04. To get to within 15 percent, she’d have to run 2:34:10. So, in reality, Ellie Gazzellie is 40 percent further from the top than I was (20.74/14.78 = 0.403). (Note that pharmaceutical companies play these very kinds of inflationary tricks when making claims on behalf of their products.)

The point is not that I was arguably as good a runner as Ellie Gazzellie. It’s that in spite of being at least as memorable on the ground, no one besides my friends even remembers that I was a runner. If I weren’t writing on this blog, almost no one on Earth would be moved to recall any of my races or finishing places unprompted.

Which, to me, is what you’d expect in the instance of someone who was merely okay in a poorly publicized sport decades ago.

I’m of course chiding Ellie not for her grandiose self-labelling—you can find far, far more outrageous examples—but because she’s a dipshit who is declaiming very confidently and contemptuously out of her Internet-ass every time I peek to have a whiff at the effluvia trailing from her social-media blowholes. Her rhetorical style is, in all seriousness, almost indistinguishable from that of Donald Trump.

Ellie doesn’t realize that the “you’re old” stuff isn’t inherently bothersome; as she’ll learn one day herself to her endless chagrin, my and everyone’s age is an objective fact.

What Ellie—who hilariously admits her to various forms of unalloyed name-calling aimed solely at men—needs to grasp, or else risk serving as a punching0bag forever, is that she can say whatever she wants about people’s age or running or writing credentials as long as she doesn’t use this as justification for shutting people or their views down—which she does all the time. And as with her fantastical claims to being an exceptional athlete, you can find even more striking and explicit examples of “Fuck him, he’s old.” When Alison Desir is being touted as a hero for a “Fuck them, they’re white” philosophy, hand-waving away the ideas of people older than you is a snap, even though it’s no different from me saying “Sounds like someone’s on the rag again,” or driving the entire conversation toward personal appearance.

When I take that dismal (and often dismally fulfilling, for a minute) route, people properly see it as mean even when they see it as justifiable and a means of illustrating others’ motivations and hypocrisy, but to my knowledge the deal has yet to work in the other direction. And there is no need for this kind of shit in any direction. It doesn’t take much to achieve honest humility as a distance runner. And although this is a whole other topic, my being old has given me the ability to watch a parade of people who overrate themselves and are desperate for attention, and literally 100 percent of them if not more leave the sport prematurely and far more unhappy than when they found it. That might be worth a moment of thought in between bouts of reformulating social-media bios.