Just to crack the top five at the Boston Marathon, Americans have to overperform

Also, qualifying races for the Olympic Marathon Trials should be restricted to loop courses

The 127th edition of the Boston Athletic Association Marathon on Monday ultimately developed into two races within races—East Africans battling for the win up front and Americans thrashing it out with other Americans a few minutes behind the main action (top results).

I think that a look back through the Bostons (an ad hoc proper noun I shouldn’t be using) that have been held on favorable or at least replacement-level weather days—and that’s maybe only sixty percent of all Boston Marathons held, given how shifting and shitty April can be in Massachusetts—would reveal this general pattern since the mid-1980s or so: One or two Americans often hanging onto the leaders for maybe 30K, but Kenyans and Ethiopians usually being well clear of domestic challengers by the time the vanguard trundles through Kenmore Square close to the 25-mile mark and Fenway Park.

It’s no secret that Kenya and Ethiopia together produce a disproportionate number of great marathon runners. but I’m not sure most people appreciate just deep the world-class talent pool in East-Central Africa is. In 2021 alone, 31 men from Kenya and 23 from Ethiopia broke 2:07:00 on World Athletics-eligible courses (in effect, loop courses). The only American man at that level right now is Galen Rupp, and even if he retains his 2:06:35 form of a year ago, he’s at most two or three years from retirement.

Meanwhile, 33 women from those two countries—17 from Ethiopia and 16 from Kenya—broke 2:24:00 last year, compared to zero American women. Keira D'Amato ran 2:19:12 in January of this year, but she’ll break 2:20:00 again when Karissa Schweizer improves on her 2020 times of 8:25 for 3,000 meters and 14:26 for 5,000 meters.

One way to look at this is that Kenya and Ethiopia together have over four dozen Rupps in store for deployment to a top-rate international marathon at any time, and about two dozen Sara Halls. And that’s if all of them run only to the level of the worst in each batch.

Since Meb Keflezighi’s win at the pathos-laced 2014 Boston Marathon and Desi Linden taking the crown in the dismal, freezing maelstrom of 2018, American running fans—who have always naturally hoped for one of their own to emerge victorious in Beantown—have become especially hungry for more U.S. athletes to contend for wins at this race. In reality, it’s surprising that an American ever come close to winning the Boston Marathon, and if the committee in charge of assembling the elite field invited thirty of the best East Africans they could get every year, it might never happen.

The big picture is that the Boston Marathon, though having become just another huge money-making parade overall, is just as tough as it’s ever been up front, at least from the perspective of an American elite hoping to contend for the win. The race doesn’t need a coterie of 2:02-2:04 men or 2:15-2:18 women to ensure that—it “just” needs a batch of 2:04-2:06 and 2:18-2:21 runners.

Meaningful Interviews? Who Needs ‘Em?

After every Boston Marathon, the running media is obligated to present a few stories in the “Why aren’t Americans doing better?” vein, even if this is a subtext rather than an explicit theme. Erin Strout’s write-up of the women’s race for Women’s Running included this passage:

Stephanie Bruce, who had previously announced that it was her last Boston Marathon before she retires from professional competition at the end of the year, placed 12th in 2:28:02. She noted that the worldwide talent is so deep right now—the times that the Americans ran on Monday would have once placed them much higher in the field not long ago.

“I think that a lot of reasons have contributed to that, but I’m glad to make it to the start line, make it to the finish line one last time here,” she said.

This is a good example of how focusing on Strout’s prickly personality, clunky sentences, and ignorance of the intricacies of running can distract readers from the fact that she’s just not a reporter. Anyone with a smidgen of curiosity—or merely a desire to churn out what people obviously want to read, personal biases notwithstanding—would have leaped through the door Bruce threw open here and asked, “Oh? Like what reasons?”

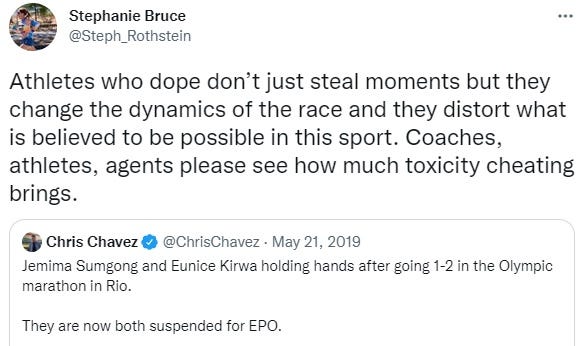

The 38-year-old Bruce, now on a self-guided 2022 farewell tour after learning of a heart condition that compelled a decision to retire from racing at the end of the year, has always been both a consistent performer and willing to speak her mind about the fragilities of the sport—and not just when it’s convenient for her image.

(I may have misjudged Alison Wade’s attitude toward the Houlihan fiasco. I don’t think she believes Houlihan is a victim of bad luck, malice, or fuckups in a Montreal lab. I think that instead she has a low tolerance for troubling news and just wants it to disappear wherever it appears.)

What a missed opportunity.

I See What CJ Albertson is Doing

Because the Americans who ran well did not win, message-board chatter centered on their pacing strategies and racing-flat choices. I get that, but I don’t think any American in the field could have beaten Scott Fauble (2:08:52 off 1:04:26/1:04:26 halves) on Monday no matter what. C.J. Albertson might have been better off running with Fauble instead of a minute ahead of him, but Albertson doesn’t appear interested at this stage of his career in pacing out marathons at just under 5:00 pace, which he knows he can reliably do. He wants a breakthrough, and he’s willing to run a lot of marathons to experience one. I hope he does.

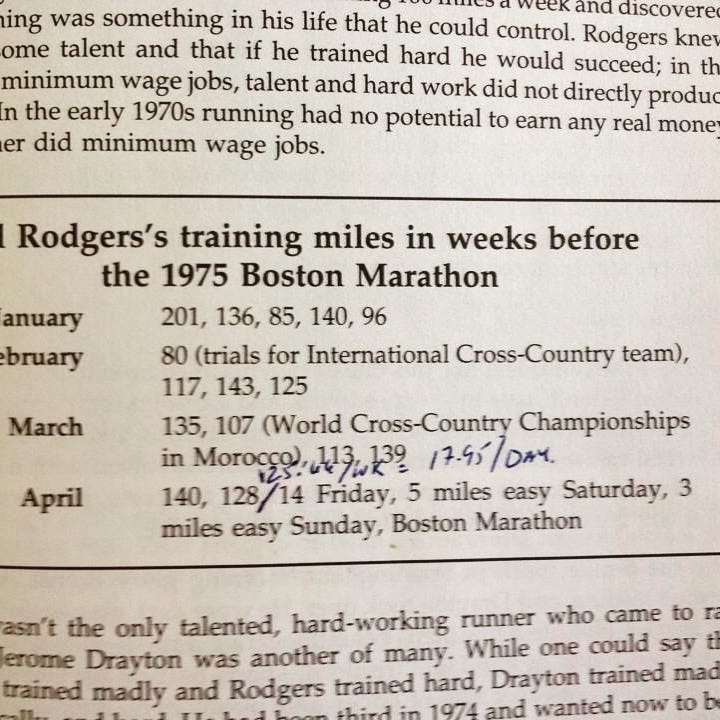

Does anyone remember Bill Rodgers? He dropped out of his first Boston Marathon in 1973, then finished 14th the next year. Heading into the 1975 edition, Rodgers’ sixth career marathon, the man who was not yet “Boston Billy” was coming off a 2:21 win at the Philadelphia Marathon in the fall of 1974.

Forty-seven years ago, Bill Rodgers stopped to tie his shoe, took about four short water breaks, and won the race in 2:09:55. I won’t say he was running in Converse All-Stars or Chuck Taylors, but his cushions on all those downhills were closer to those choices than Nike VaporFlys.

Rodgers, a full-time schoolteacher in those days, was known for how much unglamourous work he put in. Winters in Massachusetts, where Rodgers lived and trained, are not as enjoyable for training as those in, say, Flagstaff, Arizona.

Since there is ample speculation about how this runner of today would have been better off on Monday with a real carbon-fiber shoe or a different coach or more red meat or whatever, why not ponder how a 1975 Bill Rodgers could have done in the 2022 race given every advantage he’d have access to that didn’t exist in his prime?

Oh, I Sniff Jocks, Too

Bill Rodgers and I both spoke at the pre-race dinner for the 2005 Space Coast Marathon. It was probably for the best that I didn’t know this was going to happen until about three days beforehand. It was certainly for the best that I talked first. Rodgers brought world-class experience; I brought a complaint about a sports hernia, which legitimately interested him. I managed to win the accompanying half-marathon, but getting to talk to this guy for a few hours was the real treat of the weekend. Bill Rodgers is legitimately interested in anything you have to say to him about running.

The Boston Marathon is run on an aided course. Grossly so, in fact. Any course that drops more than 1 meter per kilometer of racing distance is considered elevation-aided, and that’s only 138 feet over the course of a marathon. Boston’s route loses about 460’.

Enemy-Making Proposal of the Day

Some years ago, USA Track and Field stopped allowing times run on extremely aided courses to count as Olympic Marathon Trials qualifying marks. But there was no way USATF was going to knock Boston off the list of eligible events, so, as I understand things, athletes can now qualify for the Trials on any course that loses up to about 460’ of elevation. This has resulted in the California International Marathon, which loses 328’ from start to finish with a lot less rolling than Boston includes, being a choice spot for sub-elite marathoners to qualify for the Trials.

I’ve argued myself that CIM—absent a significant net tailwind— isn’t such an easy ride that the times shouldn’t count. Some runners perform better on flat, loop courses than on courses that lose significant elevation, but also involve some climbing. But it would be silly to argue that, on average, CIM doesn’t offer a personal-best course. I doubt that a single one of the athletes who have qualified for the Trials on this course by less than a minute or two would sign up for the race if the organizers decided to run it from Sacramento to Folsom instead of the way it’s now run—and that’s even if a tailwind could somehow be assured.

The same thing goes for Boston. Yes, it beats you up. But with no wind or a tailwind and the right approach, it’s a fast course. Evans Chebet didn’t run 13:55 for the 5K stretch between 35K and 40K (4:29 pace) en route to winning on Monday merely because he felt good.

If USATF had ruled that Olympic Trials qualifying times be run on non-aided courses in, say, 2013 or 2017, it would have created an enormous stink. This is in part because almost every move the organization makes is harshly criticized by competitive runners, and this in turn is mostly because USATF’s management consists of a pack of incompetent thieves. But with the recent lowering of the women’s qualifying standard from 2:45:00 to 2:37:00, most of the runners inclined to make noises about such a thing have already been weeded out.

Perhaps qualifying for the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials qualification should be permitted only on loop courses. Any future Olympic Trials, after all, are unlikely to be run on anything besides multi-loop layouts. No more Boston or CIM. Anyone who places in the top 10 at Boston would still get to go. Or perhaps athletes could be required to run 1:00 or 2:00 faster than 2:18/2:37 on all courses considered aided—i.e., point-to-point routes (even if within the elevation limits for legality) plus illegal-drop courses up to 460’ of elevation loss.

Obligatory “Good Old Days” Comments

At a lower zoom level, the Boston Marathon, despite retaining proficiency-based, age-scaled qualifying standards, has gradually become indistinguishable from other mass marathons offering charity-bib options for gaining entry. It still carries a stoic shimmer of national and international cachet, but like most respected U.S. cultural and other institutions, it’s now coasting on a decades-old reputation.

And this is an increasingly easy sell. Every time some gimpy Boomer with a closet full of nylon gym shorts dies, and another beer-bloated Instagram bozo or high-energy ass-waggler replaces her as a nominal fan of marathon running, the average American’s expectations of any major race drop, or at least shift in the direction of “This thing I’m doing isn’t great; I am.” (This has become true of all endeavors designed to identify niche forms of excellence, because the non-excellent have never been more brazen in marketing their mundanity as praiseworthy, and demanding that we respond by intentionally mistaking the obvious taste of dogshit for fudge.)

The 2002 Boston Marathon, the last edition I finished, had 16,936 finishers. The field now routinely includes 30,000 runners, and because the start of this point-to-point race has (wisely) been moved from noon to 9 a.m., the process of shuttling all of that human mass into Hopkinton on Patriots’ Day morning has become more cumbersome. When I last went to watch in person, in 2018, the logistics of merely being a mobile spectator had become a hassle. The laxity of the qualifying standards, and the overall ease of getting into the race for those with the right connections, has made the race too big.

If the revenue from this one event weren’t driving the B.A.A.’s budget for the entire year, the organization at some stage might have considered capping the Boston Marathon field at maybe 10,000 runners by imposing stricter qualifying times. But the “Boston is special” days are gone, and most of the people noted for sounding that battle cry have died of cirrhosis.

Also, watching long races in person is now almost pointless. These days, 80 percent of spectators, at, say, the 23-mile mark of the Boston Marathon are staring at their phones for most of the hour before the first runner passes, ruining any potential drama approaching them at 12 or 13 miles an hour from the west. Many of them don’t even look up when the leaders start to go by, because they’re tracking friends or stalking randos using the race app or otherwise possessed of a need to continually manipulate an electronic device to feel at ease in a crowd. It’s nice to have such handy access to information about the developing race, but any crowd of marathon spectators within 10K of the finish line functions chiefly as a many-headed, overconfident Twitter journalist belching out spoiler alerts.