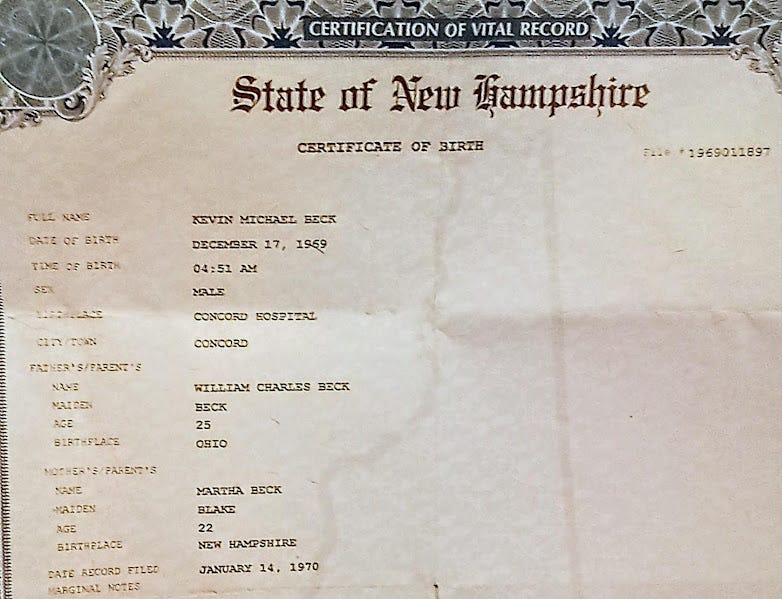

I was awake this morning—December 17, 2023—at 2:51 a.m. Mountain Standard Time in the United States. This corresponds with 4:51 a.m. Eastern Standard Time, which is what some analog clock was evidently showing when I entered the world precisely 54 years earlier in Concord Hospital in Concord, New Hampshire.

I’m not a believer in astrology, but others apparently are, and this typical description of a Sagittarius seems on target in my case in a significant number of nonrandom ways, especially the part about not being adroit at going along with the general flow of those around me when that flow seems tainted or headed off-course.

The picture below is the oldest photo of myself I have. I’m guessing it was from early 1972. My days of being a coordinated dresser with neatly tied shoes are long gone, although the determination to wear only one color remains.

For those not in the know, everyone in the 1970s under the age of thirty, male or female, wore their hair exactly like this.

My earliest memory of anything to do with politics was as a preschooler, when my dad spent about a week walking around the house muttering things like Tricky Dick” and “I am not a crook” while making vees with the middle and index fingers of both hands and holding these above his head. I did not understand, of course, that I was seeing what at one time was an assured fallout of demonstrable corruption on the part of U.S. presidents. A character like Spiro Agnew, who didn’t even last in that administration as long as Richard M. Nixon did thanks to a galactic tax-evasion scandal, would not only not have to resign today, but he’d also attack anyone who implied that he should and send the FBI after them. And today, Bob Woodward is not only still alive and working, but working as a tool of the same establishment he once helped magnificently disrupt. He is All the Liberal Networks’ Man.

My earliest sports-related memory is watching the Boston Bruins on WSBK, Channel 38 out of Boston, a large Massachusetts encampment about an hour to the southeast of Concord. The B’s were a great team in those days, with guys like Phil Esposito and Bobby Orr putting up astonishing scoring totals for the pre-Wayne Gretzky era. But I didn’t care so much about the outcomes of the games as I did about memorizing the names and jersey numbers of everyone on the Bruins roster. This habit was early notice of my orientation toward sports and a lot of other things.

I would sit on the floor near the television set as the games started with my mom and dad somewhere nearby, at least for afternoon games. I can still hear the strange WSBK jingle signifying the onset of a broadcast. My dad was frequently in vocal disagreement with calls by the linesmen in these affairs, along with the folks making calls in New England Patriots, Boston Celtics, and Boston Red Sox contests. As I recall, my dad’s contrary rulings were always correct, but never implemented on the field, ice, or court.

(Why he ever cared about any of these teams I have no idea since he’s from Ohio. It’s like a sickness back there. At least in Denver fans simply give up on pro teams when they start to suck and, between resurgences. pretend that these franchises don’t exist at all.)

Throughout early 1974, my mom developed a belly and stopped wearing bell-bottomed, or any, jeans. Though only four, I was a close observer of Sesame Street, which arrived a year before I did and which I watched without fail three times I day as a preschooler. Babies were born on that show. I knew a little about how new humans arrived, always dressed the same and alternating between unconscious or extremely vocal.

My sister Shelley was born on July 8, 1974. I have never investigated what psychologists have to say about what happens in the minds of only children at this age when they stop being only children, but I was endlessly, endlessly fascinated with my sister, her crib, and her smallness. She still has the same look on her face when she becomes surprised as she did as a baby. The first time I saw her smile on purpose, this fully established her independent personality, even her person-ness. I remember Shelley’s first words, blurted from a highchair: “I’m all done!” She’d picked that one up from me, so I was extraordinarily proud of both of us, even though I never finished my own peas in those days.

On Thanksgiving Day, I offered an example of how expected displays of theatrical yet boilerplate gratitude do not represent a useful practice for those disinclined or unable to mask their deep-seated displeasure with themselves and the world, and that it makes more sense to admit feeling beat up and expressing the reasons while acknowledging that there is always a reason for anyone to be grateful. Or at least this seems to have been my intent.

In response, a reader sent me a link to an essay on Unherd, “Stop Pretending to Be Thankful,” that explores how contemporary society has stacked the deck far in favor of individuals embracing caustic cynicism while only allowing themselves the most tepid hope. Given this collective ambience, the author, Kathleen Stock, suggests that merely exposing oneself to the things one is grateful for rather than consciously trying to keep cosmic score is a better way to live for people who are too inclined to see too much to complain about. On this view, whenever I write or even meditate about something that obviously moves me in a human way, I’m eliminating the “and I’m so grateful” psychological middleman that can instantly produce adversarial conclusions in the overly externally engaged.

If you’re in a warm place reading this, not hungry, have clean water nearby, and have solid expectations that the nearest hospital won’t soon be bombed or bulldozed, you have a reason to be grateful. Some people never have a platform even as large as this one to express themselves. Most of the world’s population, if not living in what any American would call abject misery, never gets the chance to explore even a quarter of their own creative potential. Some people are looking up at basic slavery.

It’s an amazing thing that my parents are alive and together, married for over 54 years. Fifty-four years and seven months, to be almost exact, and I was not a preemie, so maybe “Uh, looks like a really good time to get hitched” unions of this sort are not doomed for disaster.

My sister has two boys, although technically one is a man and the other will be in March. Regular readers have learned about Hayden’s collegiate running, while Joshie will graduate from high school in June.

The relatively small number of people I consider close friends has grown rather than shrunk in recent years, largely because of the writing I’ve done here. And some of those people are special, not just to me but because of the unusual trajectories of their lives. My best friend in the world was born to a 41-year-old mother in 1967, when this was almost unheard of. That mother has also become one of my closest friends, and despite how old she was when she had that little girl, she and Lize have now spent almost 57 years together on Earth. I don’t think there are many people in the annals of American history, or anywhere, who both gave birth after 40 and lived past the age of 98, given the independent rarity of both circumstances. But this is among the least special things about Janine.

This list could go on and on and on, just within Boulder’s borders. But if I did that, I would be making my own birthday almost entirely about others instead of about myself, which is considered gauche in polite American society. And though I do like to consider and express ideas pertinent to my place in the world and affecting my standing and my moods, even if the substrate is some external factor, I prefer it when these thought-streams revolve around the things I learn from the accumulated statements and actions of others around me.

I’m startled whenever I am consciously walloped by how many different literal human resources I have at my disposal, and how varied these humans are. If I weren’t confident in the power of this pool of people, I wouldn’t be able to keep banging away here at the process of trying to extract truths—etiologies, trends, useful data, whatever—from the various dishonest narratives being weaponized against the citizenry in the area of covid, race relations, human biology, and (for those interested) the bozos, hypocrites, whiners, and scammers in the running industry who have turned that environment into a glorious mess. I’d have simply flamed out long ago.

Concerning editorial tone, I think the time has come to stop pretending I should lade my posts about these clowns with righteous indignation, because the “journalists,” “coaches,” and other characters populating the joggersphere are so far beyond conventionally stupid, unaccountable, and desperately neurotic that committing to a pure heckler’s role seems both a more calming and more productive use of my discursive time. It really is hard to stay upset at people this astray even if I want to cling to all manner of justifiable resentments.

The good thing about appreciating something is that it doesn’t require justification. And appreciation is a hard quality to describe satisfactorily anyway; it’s more a sense that the item or scenario under consideration is as good as it can possibly be than it is an assessment that something possesses an unusual degree objective excellence. I appreciate getting to this point with my parents and sister and nephews alive, being in excellent health, and having a chance to determine my own immediate future every day because I’m not drunk, or dead. I appreciate having run for 54 furlongs on a sunny 55-degree afternoon today, which took me very close to 54 minutes.

And I truly appreciate having allies who are real friends as well. That can be hard to pull off when you express the things I do practically nonstop.