Malcolm Gladwell continues farting into the bathtub of running ideas

The self-sorting and defiance of reality among pliant pushers of ever-shifting pro-Nike, pro-cheating narratives in competitive running persists unabated

Malcolm Gladwell is a bestselling author, known for seeking patterns in everyday life and assembling plausible arithmetic frameworks around those numbers to sell his books. He’s perhaps best known for Outliers, which I read, but liked less than The Tipping Point. His “10.000 hours” “rule”—which he could have just as convincingly constructed around 5,000 hours or some other figure—is probably the most widely circulated of his glib but speculative ideas. He’s an engaging writer, as anyone pretending to know far more than he does about his topics needs to be.

He’s also a competitive runner of long standing, having run 4:14 for 1,500 meters as a tween, 3:55 as a collegian (worth around 4:14 for the mile) and 5:15 at age 57 in the spring of 2021, which according to age-grading tables is worth 4:20 for an “open” runner. The latter effort was a contrived duel against Chris Chavez, the gibbering, chronically shame-deficient founder of Citius Mag., an enterprise serving as a pure public-relations machine for Chavez and anyone he interviews. Chavez had evidently noticed at some point that Gladwell is not just a well-known pseudo-intellectual but also the owner of a sparkling running resume, prompting this display.

Chavez is an idiot and a weasel, but anyone possessing as rabid a hunger for attention and self-glorification as he does is bound to succeed on that front eventually, especially in a sport like professional running. The sport is now a morbid joke thanks to a combination of Wokish marketing-department arsonists feeding a jiggly cascade social-media grievance-grifters and selectively unmonitored mass-doping creating ludicrous times—marks pundits are either predictably framing as the inevitable result of shoe improvements or not mentioning the sheer unlikeliness of at all.

Chavez has also repeatedly demonstrated that he possesses a strong reverse Midas touch, drawing out the dumb in even organically smart people (e.g., Kyle Merber) and promoting podcasts hosted by alarmingly empty-headed pot-stirrers (e.g., David Melly). While it’s tempting to add Gladwell to Chavez’ list of intellectual-inversion victims after Gladwell’s self-debasing excusing of Shelby Houlihan’s doping positive last year, Gladwell has in fact been saying whimsically stupid things about running for years.

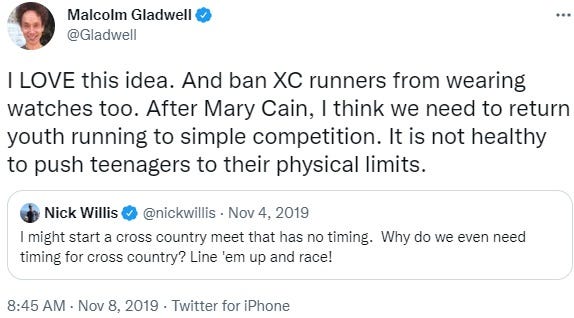

Here’s one of them. It’s from nearly three years ago, shortly after Alberto Salazar was suspended and days before The New York Times released Lindsay Crouse’s hit piece about Mary Cain’s struggles as a member of the Nike Oregon Project. Crouse’s story, like everything she churns out, was clearly a mess in real time, but was only later revealed to be the staggeringly self-serving and inept attempt at journalism it was, one more hairy little dingleberry-jewel for Crouse to add to her sprawling editorial dunce-crown.

First of all: “After Mary Cain” what? Washed out of professional track young because she wasn’t made for pro running no matter who was coaching her? Because that has become the clear consensus among insiders, i.e., people who don’t create podcasts oriented at people who constitutively keep their mouths open for ease of breathing and booger-snacking, or cavort Wokishly about on social media spouting counter-biological inanities they don’t believe while giving high-profile grifters of color encouraging shoulder-slaps.

Second of all: Okay, so Malcolm Gladwell, a teenage-running survivor who has organized much of the past 45-plus years of his life around running hard, thinks it’s a bad idea for teenage runners to run hard because Mary Cain is sad, and on top of that thinks watches should be banned too.

This is about as stupid as it gets, and here sub-four demigod Nick Willis is taking him as seriously as he would someone reading directly from Arthur Lydiard’s newly unearthed secret diary. By candlelight. But it’s nevertheless a position. Remember that.

In April 2021, filmmaker Paul Kemp produced Nike’s Big Bet, which I didn’t watch but decided was probably pro-Nike propaganda anyway. The film ostensibly tried to answer the question of whether Salazar, undeniably successful on paper, had gone too far with his methods. At the time, Erin Strout was a full-time writer for Women’s Running and immediately flew into a rage.

Strout is a shrew and as bad for the sport as Chavez, and her Twitter rage-brag that she was using her platform at WR just to sound off against men obliterated what little chance anyone besides her fellow (fella?) harpie-misandrists would read her story with an open mind. But Strout was absolutely right to dump on the film for including ten men and zero women, given what it was supposed to be exploring.

The problem is that, like literally everyone in the running media and meta-media, Strout refuses to broaden her skepticism of Salazar and the Nike Oregon Project to Jerry Schumacher, Shalane Flanagan, and the Nike Bowerman Track Club. Everyone just pretends a company founded and overseen for decades by an undisguised sociopath was going to revamp its moral code because one whiny bimbo from Long Island fizzled and proceeded to launch an unending pogrom against the dude in charge? (As I think I’ve already clarified, I think the NOP was as doping-rich as it gets, but that’s just trying to succeed as a professional running club. I’m not sure he was the human fleabag he’s been portrayed as, allowing for the fact that any successful sports coach is frequently obligated to be an asshole in both public and private.)

So, at this point, c. spring 2021, Gladwell is on record as portraying Mary Cain as both a singular reason teenage runners should chill and an outlier among gifted runners in just not being cut out for the scene. Either he thinks there are two Mary Cains or he’s just rambling with no regard for anything he has claimed to previously believe. He has lots of company in running, but he’s also supposed to have higher discursive standards than a standard-issue snapperhead.

Last September, Gladwell, now firmly ensconced in the contemporary running conversation, offered his ideas about Houlihan’s doping suspension, concluding in essence that she never would have doped intentionally owing to her acute awareness of the risk of being caught and sanctioned.

This was amazingly ignorant for a couple of reasons, though Gladwell seems unaware of one of them. The first is that this theory fails to explain the long parade of athletes whose careers have ended in humiliation after being caught for using banned substances. The second is that it’s a safe bet Houlihan had assurance from her sponsor that the contents of her piss were for practical purposes irrelevant, because a man with $54 billion can buy influence everywhere. Gladwell was and surely still is unaware or unconvinced that Christiane Ayotte wasn’t supposed to be doing her job properly on the day Houlihan’s sample reached her lab bench. (I’m only guessing about the bench.)

For those who think this doesn’t happen: Why, then, do so many athletes “get caught” only after allegedly passing a zillion previous tests? What’s most likely to have changed in these scenarios—the athlete’s doping behavior or the athlete’s standing (or that of their country or coach) in the eyes of governing officials or resentful teammates? Also, as an independent and supplementary learning exercise, feel free to explore the frustrations of former doping-lab-based scientists such as Wade Exum and Don Catlin, who have spent decades listening to dopers offer excuses from a cringle-comedy club in The Twilight Zone.

So, as of last fall, Gladwell’s complete running philosophy could be accurately described as pro-Nike, pro-Mary Cain, anti-Mary Cain, pro-professional running, and pro-doping (or at least too ignorant of necessary background to be solicited for meaningful input). But he wasn’t through muddying the picture with florid self-contradictions, and probably still isn’t.

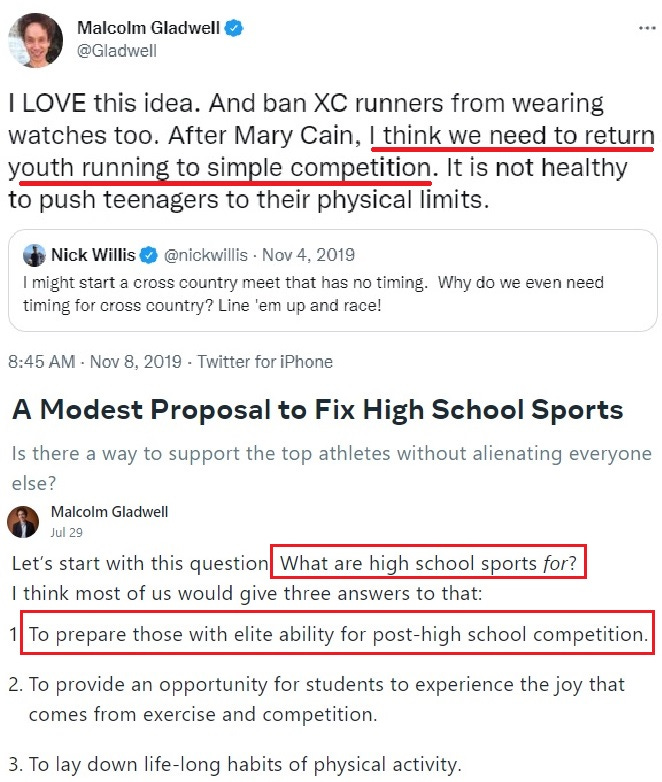

In July, Gladwell wrote “A Modest Proposal to Fix High School Sports.” His motivation was the idea that less successful high-school runners feel left out—he uses the word “alienated”—and that the solution to this reservoir of previously undetected butthurt was to change the rules of cross-country.

Gladwell cooks up several premises to support this idea, at least one of which is patently wrong: The notion that one role of high-school sports is “to prepare those with elite ability for post-high school competition.”

This means that high schools are expected to nurture and shepherd a certain fraction of runners toward elite status, all while now allowing them to use watches and discouraging over-exertion.

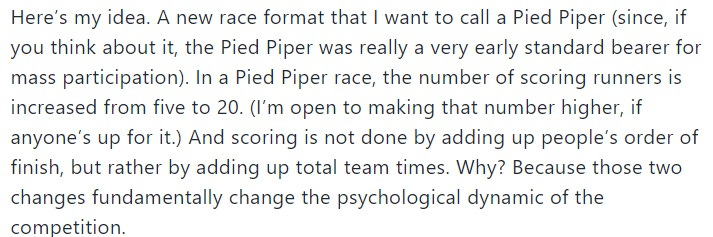

After describing something he “modestly” refers to as “Gladwell’s law,” Gladwell offers this:

Where to begin? Maybe with the fact that the Pied Piper is not a certified historical figure. But more urgently with the fact that the percentage of U.S. high-school cross-country teams that even have 20 runners on their rosters is far too small to allow implementation of this already goofy plan. How does Gladwell not know this?

I suspect that he actually does. Gladwell has made some jarringly flatulent statements Chavez lured him fully into the running convo, and he has to be smart enough to recognize Chavez’s game for what it is—not only writing and talking like an ostrich with its head in a vise because that’s how God made him, but running interference for whatever illegal or otherwise scuzzy antics anyone who runs or works for Nike is up to.

Worse than being wrong from time to time, or possibly every time, Gladwell has revealed himself to be something worse—the one thing, in fact, a self-professed intellectual should never become: An opportunist. Considering that six years ago he was commanding an $80,000 public-speaking fee, this is evidently nothing new for him. And with Gladwell having immersed himself in a sport that at the pro level is a dope-soaked monopoly and at the citizen level a circus of ass-waggling grifters and beaming self-mutilators, it’s not hard to see, maybe in less than 10,000 seconds.

How ironic that despite running supposedly being good for cognition, everyone involved in the public conversation about it seems to be hemorrhaging IQ points—often precious ones—by the podcast episode, tweet, or Instagram post.