People keep scrapbooks, Vol. 2

Henry Rono's legend was transformed from that of a one-off talent with agonizingly unfulfilled potential to a man who outpaced his own stumbles for long enough to be remembered largely as a survivor

Henry Rono, the colorful Kenyan who briefly but decisively dominated men’s long-distance track running in the late 1970s and early 1980s, died on Thursday in Nairobi at 72. Given his path, it’s surprising that Rono made it past the age of fifty. But he lived to be what most consider a respectably old man, and Rono’s story, all of it, also merits unlikely persistence and primacy in athletics lore.

Many parts of the tale strain credulity, unless you’ve been a far-gone alcoholic and a dedicated distance runner. In that case, the unvarnished chronicle of Henry Rono is still surreal. The sheer range and number of people who for years rallied around the cause of first keeping him running and then simply keeping him trackable and alive attests to the unique glow Rono brought to the sport apart from the records he set or the races he won.

I haven’t scanned more than a smattering of the tributes and obituaries piling up from around the globe, but the piece old-timers Sarah Lorge Butler and Scott Douglas assembled for Runner’s World is as succinct yet useful a summary of Rono’s career highlights as anyone could produce.

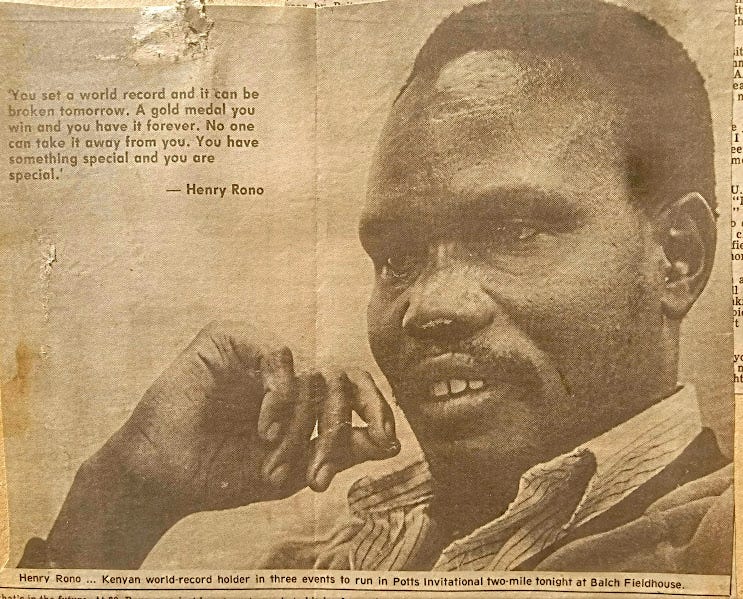

Most Boomer and Gen X running geeks, but not many others, know the two primary facets of Rono’s career. One is that in 1978, he set world records in the 3,000 meters, the 3,000-meter steeplechase, the 5,000 meters, and the 10,000 meters in an 81-day stretch. The other is that owing to Kenya’s sequential boycotts of the 1976 and 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Montreal and Moscow respectively, the most dominant distance runner of his generation not only never won Olympic gold, but never even competed in the Games.

In the current century, I repeatedly watched different online squadrons of Rono’s elite contemporaries work to help stabilize the fellow after catching wind of his latest antics. People who might not be suspected of the kind of rabid empathy I observed with this quest, which at times made even the Letsrun message board resemble a focused working group. Rono must have been a lot more than a supremely talented runner with a remarkable physical tolerance for alcohol to summon this kind of clamor on behalf of his well-being.

I didn’t extract the text of the story below because small portions of it are missing. It was published in April 1982, soon after Rono turned thirty and was slated to run a two-mile race in Boulder, Colorado on the night of the story’s publication. It’s unclear from Rono’s ARRS results whether he actually ran that race; although at the time he possessed sub-27:30 10,000-meter fitness, who knows what shape he was in by the time the gun went off at Potts Field.

My only first-hand Henry Rono story arises from a ten-mile road race I watched him run in my hometown of Concord, New Hampshire on September 14, 1986, when I was sixteen and just starting my junior year of cross-country. Being in a running environment at that stage was always a marvelous thing, ever tinged with the sense of ascendancy and slowly becoming a more significant part of what I was watching. And I liked watching 3.4-mile old home days “5K” races in the tiny towns surrounding Concord as much as I liked watching fast fields go at it.

But even then, there was already only one Henry Rono. I wouldn’t have missed watching the two-loop Chubb Life 10-Miler that morning for anything except, perhaps and only perhaps, the promise of rapidly impending sexual intercourse.

Rono ran 50:32 and was unchallenged, meaning that some of the area’s very best could have taken him—assuming he had little or nothing left. But at 34, and with a genuine beer belly that looked like a basketball beneath his tucked-in singlet, I think he could have run at least 30 seconds faster. he was smiling when he finished despite, as he’d soon reveal, being displeased with his time,

I am not sure exactly what brought Rono to Concord for the race. It’s clear from an L.A. Times story from September 25, 1987 that Rono had been leading a chaotic, couch-surfing, promise-breaking life throughout the summer of the previous year and essentially on the go all the time—training, drinking, or looking for a new roof over his head. He had (so he said) already once seen his weight briefly climb to over 200 pounds.

But in 1997, when I was working at the Concord Monitor, the staff still included a couple of sports writers who had been there eleven years earlier and recalled the nuts and bolts of the paper’s interaction with Rono. Whoever was assigned to cover the race for the paper—and I suspect that the only way to access the story today is by visiting the Concord Public Library—found Rono in the bar of the Ramada Inn, where he had been lodged by the race itself, within an hour or so of Rono crossing the finish line. He was evidently already past tipsy and waxing grandiose about his next world record, Olympics, and so on.

Henry Rono will not be the first person of exalted athletic or other status to be recalled as a great interview subject even while slowly but conspicuously killing himself. But even if his times look pedestrian today—this happened to Paavo Nurmi, it happened to Emil Zatopek, and it was eventually going to catch up to Rono, even if in the greater sense he was miraculously able to outlast the reach of some severe complications for longer than most would have bet. But either way, in what’s now a dizzying sea of personalities and athletes and post-insane times, the man stands as one-of-a-kind portrait of athletic and consumptive excess who alternated heretofore unforeseen triumphs with excoriating pratfalls. He was as superhuman as any runner for a while, but also as absolutely human as anyone can be.