People keep scrapbooks, Vol. 3

Inventing and invoking superfluous terms like "RED-S" is just a way for today's history-averse joggers to frame themselves and their subjects as brave revolutionaries

This post includes two articles that together contain multiple first-hand accounts from accomplished runners of both sexes who experienced eating disorders during their competitive careers.

The first of these originally appeared in the Boulder Daily Camera in the spring of 1983 (exact date unknown) and therefore became eligible for masters-division competition last spring when it turned 40. The second was originally published in RT—yes, that “RT”—in April 2000 and thus became eligible to legally consume alcohol in the United States right around the time the nation rolled out the covid injections at scale and began using these, drug overdoses, anti-social-cohesion measures, and other miseries to effective combat what had become an irritatingly high U.S. life expectancy (79 years in 2019, but down to 76.1 by 2022 and therefore predicted to drop to zero right around the end of the century).

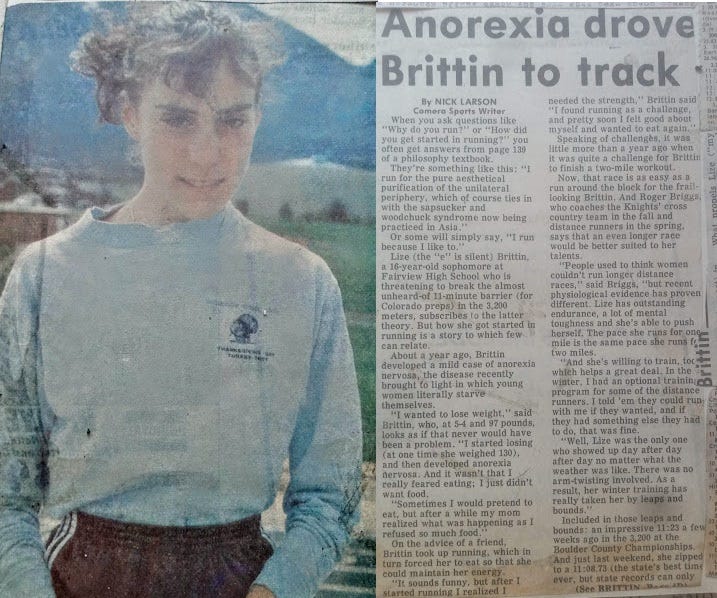

Anorexia drove Brittin to track

By NICK LARSON

Camera Sports Writer

When you ask questions like "Why do you run?" or "How did you get started in running?" you often get answers from page 139 of a philosophy textbook.

They're something like this: "I run for the pure aesthetical purification of the unilateral periphery, which of course ties in with the sapsucker and woodchuck syndrome now being practiced in Asia."

Or some will simply say, "I run because I like to."

Lize (the "e" is silent) Brittin, a 16-year-old sophomore at Fairview High School who is threatening to break the almost unheard-of 11-minute barrier (for Colorado preps) in the 3,200 meters, subscribes to the latter theory. But how she got started in running is a story to which few can relate.

About a year ago, Brittin developed a mild case of anorexia nervosa, the disease recently brought to light in which young women literally starve themselves.

"I wanted to lose weight," said Brittin, who, at 5-4 and 97 pounds, looks as if that never would have been a problem. "I started losing (at one time she weighed 130), and then developed anorexia nervosa. And it wasn't that I really feared eating; I just didn't want food.

"Sometimes I would pretend to eat, but after a while my mom realized what was happening as I refused so much food."

On the advice of a friend, Brittin took up running, which in turn forced her to eat so that she could maintain her energy.

"It sounds funny, but after I started running I realized I needed the strength," Brittin said "I found running as a challenge, and pretty soon I felt good about myself and wanted to eat again."

Speaking of challenges, it was little more than a year ago when it was quite a challenge for Brittin to finish a two-mile workout.

Now, that race is as easy as a run around the block for the frail- looking Brittin. And Roger Briggs, who coaches the Knights' cross country team in the fall and distance runners in the spring, says that an even longer race would be better suited to her talents.

"People used to think women couldn't run longer distance races," said Briggs, "but recent physiological evidence has proven different. Lize has outstanding endurance, a lot of mental toughness and she's able to push herself. The pace she runs for one mile is the same pace she runs for two miles.

"And she's willing to train, toc which helps a great deal. In the winter, I had an optional training program for some of the distance runners. I told 'em they could run Cer with me if they wanted, and if they had something else they had to do, that was fine.

"Well, Lize was the only one who showed up day after day after day no matter what the weather was like. There was no arm-twisting involved. As a result, her winter training has really taken her by leaps and bounds."

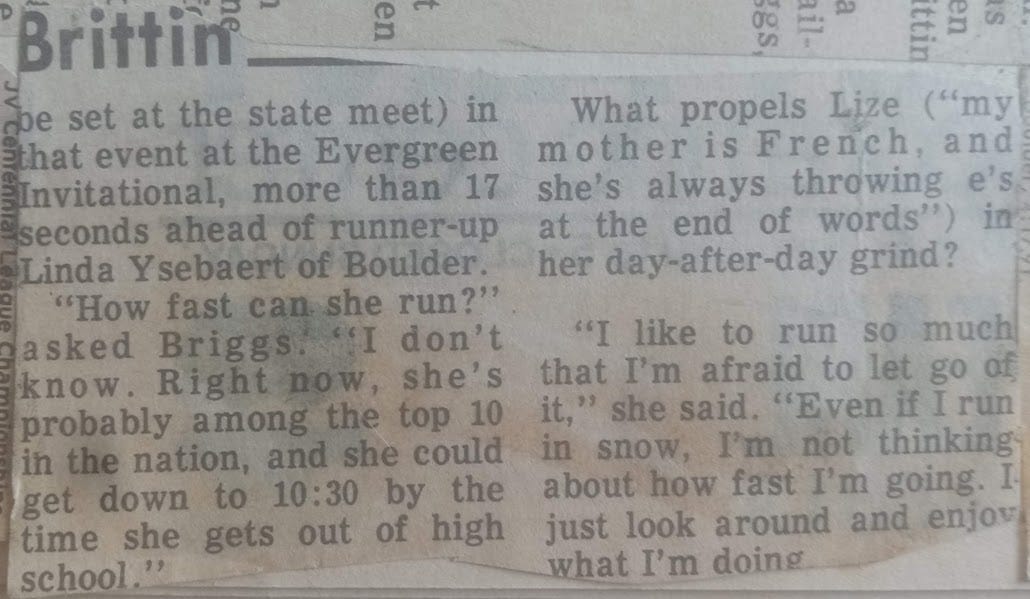

Included in those leaps and bounds: an impressive 11:23 a few weeks ago in the 3,200 at the Boulder County Championships. And just last weekend, she zipped to a 11:08.73 (the state's best time. ever, but state records can only be set at the state meet) in that event at the Evergreen Invitational, more than 17 seconds ahead of runner-up Linda Ysebaert of Boulder. "How fast can she run?" asked Briggs. "I don't know. Right now, she's probably among the top 10 in the nation, and she could Eget down to 10:30 by the time she gets out of high school."

What propels Lize ("my mother is French, and she's always throwing e's at the end of words") in her day-after-day grind?

"I like to run so much that I'm afraid to let go of it," she said. "Even if I run in snow, I'm not thinking about how fast I'm going. I just look around and enjoy what I'm doing."

The reproduced version of the article below retains all of the elements of the original except for a list of links that have all passed into electronic graveyards or worse.

I believe the runner on the cover is Libbie Hickman.

The Thin Men

More male runners suffer from eating disorders than you think

by Kevin Beck

Steve is a runner with a resume few wouldn’t envy. His personal bests range from a 29:00 10K to a sub-2:20 marathon, and he’s active in the sport in both administrative and volunteer capacities. Steve’s acquaintances say that although his hell-bent-for-leather training regimen and competitive drive are ferocious, he’s one of the more ebullient personalities on the road-race circuit.

Inside, Steve (who asked that his real name not be used) wages a different battle. His first steps of every day lead not out the door for a training run, but to the bathroom scale. The numbers that bounce back at him determine what sort of day Steve will have—as much as will the quality of that morning’s jaunt or the afternoon’s speed session.

“I don’t know when I realized something wasn’t right,” says Steve. “I had a rough time in college, a lot of depression for no apparent reason. Unfortunately, trying to take control included taking control of food. I slowly ended up where I am now—obsessed.”

Steve reveals behaviors such as buying groceries and seeing how many days he can keep them on hand without eating them (and, he hopes, end up throwing them out). He’ll put junk food in his car to tempt himself; he “wins” by not eating it. When hunger strikes he’ll fill up on water.

At five feet, eight inches, Steve maintains a weight of 120 pounds, always hoping to “drop a couple more.” Several years ago, when he was sidelined by an injury, he crosstrained fervently and limited his daily food intake to a single spartan meal of greens.

“I guess by doing these things I’m only setting myself up to lose,” Steve admits. Yet he has never sought help for his behaviors and feelings; indeed, only a few close friends know about them. For now, Steve accepts that. “I usually just kind of do what I do and don’t think about it much. I’ve come to realize that’s me. I can live with that.”

Male runners like Steve are probably not as rare as you think. Most likely you know at least one woman runner with a blatant eating disorder, but among men, attitudes and practices like Steve’s are veiled by intense shame and masked by competitive exploits. Although ignorance, denial and rationalization are characteristic of anyone with disordered thoughts or behaviors surrounding food and weight, in males these are amplified by the

issue of gender.

Who suffers?

Approximately eight million people in the U.S. have a clinically defined eating disorder. According to most sources, about 10% are men, but experts universally agree that percentage is probably higher. A research project conducted by the NCAA revealed that the sports with the most male participants with eating disorders were wrestling and cross country.

Several factors contribute to the murkiness of available data. One is that an eating disorder is typically perceived as a feminine problem. “Men are hesitant to seek medical attention for a disorder they fear will be seen as a girl’s disorder or a gay guy’s disease,” wrote Arnold Andersen, M.D., author of “Males With Eating Disorders” (Brunner/Mazel, 1990), in the September 1995 issue of Psychiatric Times. (Anderson notes that 21% of males with eating disorders are gay.)

A second reason problems fail to come to light follows from the first: A lack of suspicion among the runner’s closest allies—friends, coaches, family members, even medical professionals—even when signs that would implicate a female are manifest. For example, it’s socially acceptable for a man, especially a super-active one, to wolf down a huge amount of food; few would suspect he might be bulimic. Similarly, a guy who never seems to eat anything might be called “picky,” but rarely draws attention to himself as a result. And one of the cardinal signs of anorexia in women—irregular or absent menstrual periods—obviously doesn’t apply to men.

According to Andersen, “Males with eating disorders have been relatively ignored, neglected, or dismissed because of statistical infrequency or legislated out of existence by theoretical dogma.” In plain terms, most people don’t bother to consider the possibility that their male training partner, that lean, mean racing machine, may in fact be in desperate need of intervention.

Poke around among runners you know, and almost everyone will have a story about some guy with “weird eating habits.” Seldom, however, would the fellow in question be thought to have a true eating disorder. Even when a real problem is suspected, action is seldom taken. In soliciting personal accounts for this article, I heard from more than a few concerned wives, girlfriends and parents of affected men. “My husband can barely pull the skin an inch away from his ribs,” one woman wrote. “Yet he thinks he’s fat. I know disordered thinking when I see it, and when he looks in the mirror, I’m sure he sees an obese man staring back at him.”

What puts men at risk?

“Female athletes are generally expected to know how to cook and prepare healthy meals, while males can simply claim a lack of time or knowledge—they’re too busy balancing a career with training, for example,” says Suzanne Girard Eberle, M.S., R.D., a sports dietitian and former elite runner. “Sure, this may indicate poor cooking skills or a lack of commitment to visit the grocery store every week, but in some cases it’s an easy front for male athletes with disordered eating habits to hide behind.”

The result of these factors—deep shame and a lack of external confrontation—is that if a man does seek help, it’s only after he’s had a disorder for years, which in turn makes the disease much more difficult to treat.

Another risk factor is that men drawn to running are often culled from a distinct psychological subset of the population. “Participants in sports that emphasize a lean body are naturally at higher risk for developing an eating disorder than others,” says Dr. Jean Bradley Rubel, creator of Anorexia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders, a non-profit organization that provides information about eating disorders. She notes that although females in Western countries, subject to social pressure to be thin, are especially at risk for developing an eating disorder, competitive runners of both sexes live in an environment that may overvalue performance, low body fat and an unrealistic body shape, size and weight.

In such a world, men with no previous compulsions with regard to their weight or diet may become caught up in calorie counting and body-image concerns to the point that that these issues, rather than training and racing, become their primary focus. I remember weighing myself in my freshman year in college after a cross-country practice, simply to satisfy my curiosity, and watching the scale’s needle settle at 138. (I’m five feet, 10 inches.) A few weeks later I had the workout of my life, running a series of mile repeats under 5:00 for the first time ever. Back in the locker room afterward, still sweating and exalted, I casually hopped on the scale and was surprised—and a little unsettled—to see a “142” glaring back at me. Without any conscious thought, 140 had apparently become my barometer for what I deemed acceptable—even though I had just proven myself fitter and faster than ever, the theoretical goal of any competitive runner’s training program.

These days I still top off at around 140, and having continued to set PRs at that weight I’ve let go of obsessing over it. But I know that if I were to suddenly find myself at 145, I’d make every effort to get back to “normal” immediately.

“In a sense, eating and exercise disorders are training programs gone horribly wrong,” notes Bradley Rubel. “[A runner] wants to lose weight to improve performance, but then loses control and ends up with body and spirit ravaged by starvation, binge eating, purging and frantic, compulsive exercise. What may have begun as a solution to problems of low self-esteem has now become an even bigger problem in its own right.”

Men vs. women

None of these stories are unusual. The important question is, at what point does the wish to lose a couple pounds edge from questionable to downright unhealthy?

First, it’s important to realize that lowering weight or the desire to do so does not necessarily signify the presence of an eating disorder. After all, for distance runners, there’s a valid argument for maintaining a weight well below Western society’s definition of “normal.” Nonetheless, some men engage in practices that the general public—and most runners—would deem outrageous.

Take Craig Brenner, a 32:28 10K runner from Massachusetts. Carrying 142 pounds on a five foot, seven inch frame hardly qualifies him as a leviathan, but last summer Brenner embarked on a 60-day quest to drop to 127, part of a plan to bring his 10K under 32:00. His regimen was 70 miles a week, intervals, strength work—and 1,000 calories a day.

Brenner says he thinks he looks fine at 142—a weight he admits

he has trouble reducing—but likens the 15-pound differential to “carrying three five-pound bags of sugar around the 10K course.”

“It’s hardly a ‘disorder’ in my mind,” Brenner says, “but maybe I’m in denial.”

This highlights a key factor in any disordered eating situation: The underlying issue is not appearance or athletic achievement, but unresolved emotional conflict. In fact, in the absence of such a conflict, the diagnosis of an eating disorder cannot be made; “functional” weight loss as exemplified by Brenner’s plan—no matter how obsessive—does not count (see “Eating Disorders Defined”).

According to Bradley Rubel, risk factors for developing an eating disorder do differ between the sexes. For men, they include obesity as children, recent dieting (also a key factor for women) and participation in a sport or profession demanding thinness. Like women, many affected men come from dysfunctional families where physical or sexual abuse or alcoholism played a role, and the eating disorder arises as a coping mechanism to deal with these issues.

Males typically develop eating problems later in life than females, possibly because most males are not exposed to the same cultural pressures to be thin that women and girls are. Rather, most men equate excessive leanness with weakness and fragility. Runners, of course, often feel differently. As Andersen notes, “When subgroups of males are exposed to situations requiring weight loss—such as occurs with runners—then a substantial increase in [anorexic or bulimic behavior] follows, suggesting that behavioral reinforcement, not gender, is the crucial element.”

Most of the underlying psychological factors that lead to an eating disorder—low self-esteem, depression, anxiety and difficulty coping with day-to-day challenges—are the same for both men and women.

“Just as with women, control is a central theme,” says Girard Eberle. “These men are rigid and restrictive when they eat, ignoring natural hunger cues.”

Running’s role

It seems unlikely that running, even at the highest competitive level, can “cause” an eating disorder; rather, men whose backgrounds, psychological profiles and emotional status fit a certain mold are probably more likely to be attracted to running and other forms of intense physical exercise than the average person. Thus they are placed in a situation ideally suited to unleash eating-disorder-like symptoms

It’s also worth noting that although there are strict criteria for diagnosing an eating disorder, problems fall along a spectrum of severity. It is often difficult to determine when eating- and weight-related concerns begin to affect a runner’s physical and emotional health to such an extent that professional help is needed. As Andersen says, “The process of transition from a normal behavior such as dieting to a fixed illness has not yet been well-defined.”

According to Girard Eberle, typical disordered eating habits that can point to a deeper problem include avoiding “real” food in favor of energy bars, meal-replacement beverages and the like; never planning and sitting down to eat meals; and sticking to just a few “safe” foods.

With men, the obsession with shape seen in women is often absent; instead, a fixation on food and weight is the driving force. For runners, the pressure to succeed—a “win at all costs” attitude—can contribute to the onset of a problem. It is also more common for male sufferers to have simultaneous problems with alcohol or drug abuse.

Difficulties outside running may trigger a problem. “I often see males worrying about their weight when personal relationships aren’t working out,” says Girard Eberle. “They pour their time and energy into their training. This includes weighing themselves up to several times a day ‘just to see how their training program is going.’ It’s trying to control their weight when other areas of their life are out of control.”

Getting help

Regardless of root causes, anyone whose eating has become disturbed enough to produce clinical signs needs intervention. The physical dangers and complications associated with an eating disorder can be life-threatening.

A man might be reluctant to seek help because he fears winding up in a room full of women, and in fact this may be the case, as there aren’t a lot of eating-disorder specialists specifically trained to treat men, according to Anderson.

If you know—or are—a male for whom this subject rings alarm

bells, what can you do? For starters, here’s a list of suggested do’s and don’ts for concerned friends and family members, provided by the Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Association:

DO be sensitive to the fact that your friend will find it difficult having what’s labeled a “woman’s disease.”

DO encourage him to seek help. If you’re concerned about his medical condition, talk with a professional and make your concerns known, but tell him about your plans first.

DO get information about eating disorders.

DO realize that recovery takes many months or even years to accomplish.

DON’T be offended if he doesn’t listen to your advice. The eating disorder can feel much bigger than he is; it’s not as easy as just wanting to stop.

DON’T get pulled into conversations about appearance. Arguing about his weight and shape will never work.

DON’T bug him about eating. He’s already too focused on food and diet.

Most of all, it’s important for everyone—top-notch competitor, twice-a-week shuffler, coach, friend, parent, loved one—to remember that regardless of a runner’s goals, his health is paramount. The steps you take today, difficult as they may be, might lead to many more happy ones down the road.

Even the Elite Fall Prey

Gary Romesser, 49, one of the country’s top-ranked masters runners, speaks candidly of his earlier experiences with compulsive weight control. “At age 29, I felt I had a good shot at qualifying for the Olympic Trials,” he says. “To get [there], I believed ‘the lighter, the faster.’ “Romesser ran 140 to 160 miles a week and aimed to drop “excess” weight. “I’d read the charts,” he says. “Somewhere it said a small-framed, five-foot, seven-inch male runner’s ideal weight was 108 pounds.” With that goal I mind, Romesser began limiting himself to two meals a day—“meals” that were often no more than crackers and fruit. “I lost the weight and the strength with it,” he says. “At 112 pounds, I couldn’t even stay on my feet without hurting and being tired all the time.”

Arriving at his goal race with the feeling that he was in peak form, Romesser fell back from the outset and dropped out at the mile mark. Stunned and disillusioned, Romesser went to a post-race buffet dinner offered by the race management and found himself craving and eating everything in the food line.

“I was so hungry and my stomach so small, I couldn’t keep it down,” he says. “But I returned to the food line for more! I was shocked at what was happening.”

Romesser cut back his training and slowly gained weight—which he began to understand was necessary. “As I started back running, I got back to some healthy eating habits. I just wanted to feel normal again,” he says. “That took six months, and it took another year and a half before I had my weight back up to 124.”

Determined to return to the racing scene, Romesser switched his focus from weight control to sports nutrition. “I focused on three meals a day and had good snacks whenever I got hungry,” he says. “My best running weight came back and I finally started feeling normal and healthy again. Now, I eat almost everything I want.”

Reflecting on his experiences, Romesser says, “I learned from my mistake and I will never go back to that unhealthy, painful deprivation.”

Brad’s Story

Although I am only 17 years old, I have suffered the pain an eating disorder puts its victims though. When I was younger I ran quite a bit. But sometime around the third grade I dropped the sport. As a high-school freshman I weighed 155 pounds at five feet, nine inches. I smoked cigarettes. The “running thing” just wasn’t in me then.

By my sophomore year, I was unhappy with almost every aspect of my existence, so I turned to the one thing that I’d been happy with in the past—running. It was hard to resume a running career, but I was determined and driven. I felt in control when I was running. It was something no one else could tell me how to do.

This led me to begin controlling other areas of my life as well. I was still unhappy with a lot of things. When I’m sad, I eat; when I eat too much, I gain weight; when I gain weight I can’t run. So it became a pleasure to constantly monitor what went into my body, to calculate my daily calorie intake and carefully choose a list of foods that I could eat the next day.

My weight dropped slowly, from 155 to 150. Then 142. People noticed I was getting thinner, but my running felt so strong. On Thanksgiving Day, 1997, I left the dining room table with the excuse that I needed some fresh air. I went behind the garage and practically cut the back of my throat to shreds with the teaspoon I'd slipped into my pocket, but when all that food came up, I felt a sense of relief greater than any I’d ever experienced.

It hit me that I could control my weight by making myself throw up. After breakfast at home. After lunch in school. After dinner in the Olive Garden. Anywhere.

My weight eventually dropped below 130. By this time I lacked the physical energy to run, but something drove me to continue, even as my head screamed, “This is enough.”

My friends finally convinced me I needed to change my behavior. My weight gradually increased. My running performances slowed quite a bit, but I couldn’t take any more of the throwing up that had consumed my life, yet somehow made me feel good about myself.

Cutting back on food became my plan again. I limited myself to one blueberry bagel a day. I wouldn’t eat breakfast, I’d have water for lunch, I’d go home and do homework, and then I’d run my 2.5-mile course. Only after that would I eat that bagel, my lifeline. I’d fall into a heavy sleep at 7:00, tired from running and the mental exhaustion that an eating disorder inflicts on its victims.

My weight dropped to 127 in two to three weeks. I’d run with a plastic garbage bag over my chest to lose water weight, and then sleep with it on, finally removing the dripping-wet bag the next morning. I was obsessed.

Then I couldn’t take it anymore. I had lost control of the one thing I could control, and everything in my life had suffered as a result: my family, my friends, my academic performance. In April 1998, one week before my first track meet, I gave up running as well. I gave up starving and I gave up controlling everything. My weight shot up over the next few months, and as a reaction to this I did, just once, make myself throw up. I sat in tears on the bathroom floor for the next 10 minutes.

In the fall of 1998 I ran cross country. I had my friends watch out for me and with their help maintained a weight of 151 pounds. I wasn’t a perfectionist; I was only ranked 10th on the team. Sometimes I’d still think that maybe I could have been better if I was under 130 pounds. But although I was slower, I was miles ahead of where I’d stood only a year earlier.

Eating Disorders Defined

Anorexia nervosa is characterized primarily by self-starvation and excessive weight loss.

Symptoms include:

refusal to maintain weight at or above a minimally normal weight for height and age

intense and irrational fear of weight gain or becoming fat, even though underweight

distorted body image (e.g., “feeling fat” even when emaciated or believing one area of the body is “too fat” even when obviously underweight)

in females, loss of three consecutive menstrual periods when otherwise expected to occur

extreme concern with body weight and shape

The possible health complications of anorexia nervosa include:

fat and muscle loss

hair loss

slow pulse and low blood pressure

decreased ability to concentrate

depression

chronic fatigue

insomnia

stress fractures/osteoporosis

overuse injuries

cardiac arrest

Bulimia nervosa is characterized primarily by a secretive cycle of binge eating followed by purging.

Symptoms include:

repeated episodes of bingeing (rapid consumption of large amounts of food in discrete period of time)—at least two episodes a week for at least three months

feeling out of control during a binge

purging after a binge (self-induced vomiting; use of laxatives, diet pills or diuretics; excessive exercise; fasting) to avoid weight gain

frequent dieting

extreme concern with body weight and shape

The possible health complications of bulimia nervosa include:

swollen glands and sore throat

dental and gum disease

esophagitis/esophageal tears

depression

fatigue

electrolyte imbalances and dehydration

constipation or diarrhea

laxative dependence

cardiac arrest

Adapted from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, edited by the American Psychiatric Association, 1987; and Eating Disorders Awareness & Prevention (EDAP), Inc., 1996.