Raise your marathon plateau

Still looking for that breakthrough race? These strategies can take you there

If you're a seasoned marathoner hungry for a breakthrough, by now you've probably seen more training schedules than you can shake an energy bar at. The recipes vary, but the ingredients are the same: long runs, interval workouts, tempo runs, easy days, marathon-pace (MP) runs. Buried somewhere within one of these prescriptions, you believe, is the PR-shattering formula guaranteed to lift you from your current performance plateau.

But in evaluating marathon-training plans, you've perhaps lost sight of a critical practice: focusing on general guiding principles and day-to-day strategies, not merely on executing a particular series of workouts.

Fortunately, there's nothing complicated about solidifying your foundation. Whether you're a marathon veteran or a newcomer to the distance, the strategies described here can help you parlay your week-by-week training into that performance leap you've been looking for on race day. You'll see no mention in this article of specific workouts or weekly training plans, because chances are you've found one of those already. Rather, the principles touched on here will help maximize the benefits of whatever sensible, structured pattern of workouts you've settled on.

Hit the dirt

When a runner shifts from a typical training diet into full-scale marathon-training mode, often the most significant change is an increase in mileage, both in per-week totals and the weekly or biweekly long run. Clearly, high mileage is a key determinant of marathon success; however, it is also a common stumbling block, as many athletes can't seem to exceed particular training volumes without incurring injuries or succumbing to staleness or fatigue.

One way to dodge the injury bugaboo and still put plenty of miles in the bank is to run on soft surfaces. Ask yourself how often you really make an effort to avoid asphalt and concrete. When faced with a 15-minute drive to a trailhead or a two-second bop to the end of the driveway-especially after your daily commute, which are you honestly going to choose?

I've always preferred the solace and variety of trails to the unwelcome buzz of urban perambulation. But it wasn't until I got a dog for a running partner and trained on trails almost exclusively out of concern for his legs that I began to really appreciate the benefits of running on grass and dirt. Not only did my legs feel fresher during 100-mile weeks than they had at 60 to 70 per week on macadam, but I was reaping benefits I didn't even know about.

It's not just the diminished pounding that helps keep a trail devotee healthy. In addition, running on slightly non-uniform surfaces calls a variety of muscle groups into play in ways running on pavement does not. This strengthening of the support muscles can play an important role in forestalling aches and pains as well.

There's at least one good reason, however, for occasionally running on hard surfaces. As John Kellogg, a Dallas-based coach of national-class runners says, "If you train exclusively on soft surfaces and then suddenly switch to long races on the roads, you're very likely to get injured or at least require prolonged post-race recovery time." Kellogg adds that although his high-mileage runners do between 50% and 65% of their running on soft surfaces to develop joint integrity and reduce impact stress, his athletes do most of their fast continuous runs, such as MP sessions, on the roads or track in order to ensure consistency in footstrikes and rhythm.

The main lesson? It's probably worth going the extra mile to find forgiving surfaces to run on between more directed efforts. If you truly don't have access to soft trails, try running on the soft shoulder of a road if the surface is smooth and level. During marathon training, footfalls add up quickly, and the overall decrease in stress burden achieved by foregoing tarred roadways can be tremendous.

Up the tempo

According to exercise scientist and coach Jack Daniels' widely accepted definition, a tempo run is a 20-minute effort at anaerobic threshold (AT) pace, also known as lactate threshold pace. Although the benefits of these bouts are well studied, marathoners may gain even more from a similar workout that pushes the envelope: runs at or near AT pace sustained for up to 15 miles. Examples of these "overtempo" runs include six to seven miles at 10-mile race pace, and eight to 10 miles at half marathon to 25K race pace. "These sessions work exactly the same systems as shorter AT runs, but because they are held longer they provide a greater stimulus for improvement," says two-time Olympic marathoner and exercise physiologist Pete Pfitzinger.

Because these efforts are more taxing than standard tempo runs, they require higher levels of pre-workout rest and post-workout recovery. Kellogg suggests that for these reasons, such sessions be limited to no more than one every two to three weeks for maximal effectiveness, recovery and integration into the overall training scheme.

Many runners balk at doing workouts so perilously akin to all-out racing. However, if your objective is a fast marathon, you won't be doing many tune-up races anyway; those you do should be chosen in advance and treated as stepping stones to success at 26.2 miles rather than benchmarks in their own right. Those who have the discipline can use these races for their overtempo runs.

Run on empty

One of the benefits of endurance training-and the long run in particular-is that it teaches the body to adapt to intense effort in the face of depleted energy sources. Shifts from carbohydrate to fat metabolism and the recruitment of muscle fibers in a particular sequence both occur toward the end of a prolonged work bout, especially an intense one. These conditions are difficult to mimic using other workouts. As Pfitzinger says, "The only way to teach your body to use fat 'more effectively' is to increase the volume of training and the duration of long runs."

But another physiological adaptation-an increase in muscles' capacity to store glycogen, the body's storage form of carbohydrate-can be achieved in a number of ways, the long run being only one alternative. "Any time you deplete your glycogen stores, you provide a stimulus for your body to store more glycogen," says Pfitzinger. Because this increases your chances of getting to the finish line without running out of gas, it is therefore of benefit to anyone bent on peak marathon performance.

One way to deplete your glycogen stores is to stop eating. Obviously, this is not a wise choice. However, an occasional, carefully planned reduction in carbohydrate intake combined with certain forms of training can instruct the body to deal with situations of low glycogen availability.

Here's an example: Do an evening or late-afternoon 10- to 12-miler at a moderate pace, eat a low-carbohydrate dinner (fewer than 100 grams of carbohydrate), then get up the next morning and run another 10 to 12 miles. You'll likely feel lead-legged toward the end of the morning session, but "running on fumes" will boost your body's level of the enzymes that facilitate glycogen storage. This in turn results in your muscles having an increased hunger for glycogen and a greater capacity to store it.

It is critical to ingest plenty of carbohydrates following the second run so that hard training may resume within a couple of days. In addition, drink plenty of water before, during and after both runs. This depletion-supercompensation cycle should be attempted infrequently-not more than once every three weeks or so. Intersperse these training sessions with your long runs in such a way that adequate recovery (seven to 10 days) is allowed in between.

A lot to swallow

The purported interplay between nutrition and optimal running performance has resulted in an explosion of gels, supplements and sports drinks. While the runners of the 70s seemed to survive without them, what goes into your system-and when-is an important consideration for runners, and becomes increasingly critical as weekly mileage rises, in order to prevent muscles from becoming glycogen-depleted.

Most marathoners are aware of the need to load up with extra carbohydrate and fluids before long races and long runs. They are, however, often lax about their day-to-day eating and drinking habits, which can affect the ability to train at their desired mileage and intensity. "If you are training more than 60 miles per week, then you need extra snacks or small meals to get in enough calories and carbohydrates," says Pfitzinger.

Research has shown that the sooner carbohydrates are ingested after running, the more quickly glycogen stores are replenished. Therefore, bearing in mind that as a marathoner-in-the-making you're probably only a few miles away from glycogen depletion much of the time, you should be in the habit of keeping something-a sports drink, some fruit-on hand for consumption after every training run.

Kellogg suggests that taking some ordinary table sugar within the first 45 minutes after a depleting workout, followed about an hour later by a meal rich in complex carbohydrates, is perhaps the best way to replenish glycogen stores. Though many runners don't like to eat immediately after exercising, you can think of it as part of your training, as important as a proper cool-down.

Twice is nice

One common question asked by runners dabbling in higher mileage is: What are the relative merits of running twice a day rather than once, even if the overall mileage is the same?

In simple terms, running twice a day will make you a "stronger" runner, while running the same distance once a day carries purely aerobic benefits not gleaned in a pair of shorter runs. Some coaches and physiologists feel that distributing a given number of miles among more runs reduces the likelihood of injuries, since most non-acute running ailments befall runners toward the end of their jaunts.

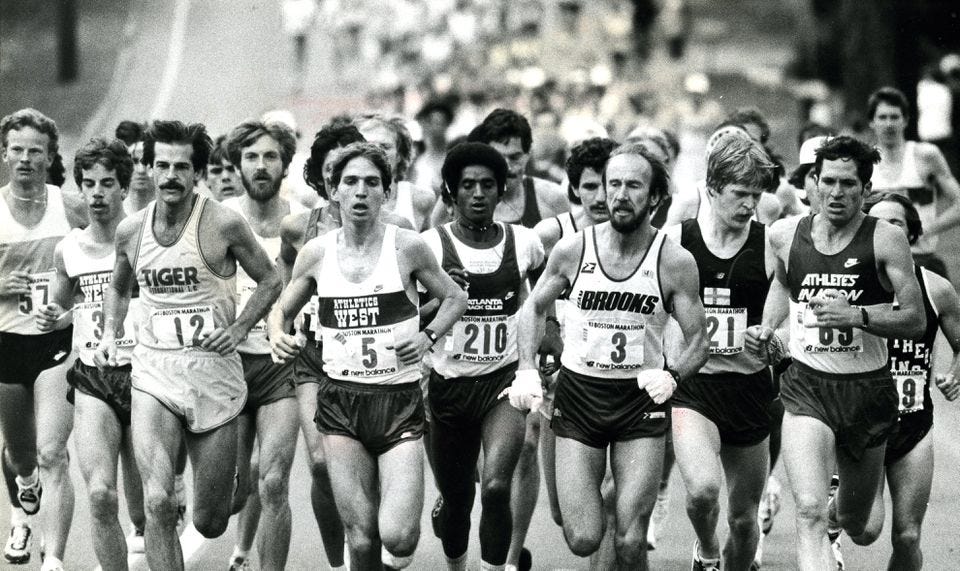

The bottom line is that running twice a day is extremely useful in raising your overall mileage, and, based on the results of the current crop of Japanese marathoners and the American greats of the 70s and early 80s, raising your overall mileage is the surest route to marathon success. Says Kellogg, "Consistent high mileage over a number of years is by far the most important element for success in running." If you've never experimented with twice-a-day running, begin cautiously-a pair of easy three- or four-mile runs for a few weeks, then three of them, building on the length and frequency as much as your time and energy allow.

How fast, how far?

It's tempting to pigeonhole long runs into two distinct types (I'm guilty of this myself): "ordinary" long runs done at an easy pace for the simple purpose of building endurance, and MP runs meant to mimic race conditions as closely as possible. But there's an in-between zone with distinct benefits: picking up the pace in the last half-hour or so of an otherwise easy long run to near-marathon pace.

In physiological terms, the utility of this is that it helps mimic marathon conditions by hastening glycogen depletion and teaching the body to run hard while tired. "Slow long runs do not prepare the body in the same way," says Pfitzinger. Adds Kellogg: "'Pace' pickups will mobilize the muscle fibers and access fuel sources in the correct sequence for racing, and will also train the heart, respiratory muscles, motor neurons and muscle groups to function more strongly and efficiently throughout all endurance events."

Don't hesitate to pick it up toward the end of an easy long run for fear of compromising the purpose of the workout. If you're well hydrated and feeling comfortably fatigued, increasing your pace to within 10 to 20 seconds per mile of marathon pace over the last four or five miles can greatly increase the benefits of the workout without adding significant lingering fatigue.

Look ahead

Many marathon-training plans are structured over a three- or four-month period. For many runners, however, three months is simply not enough time to build the strength needed to truly master the marathon distance. The reality is that for most of us, a marathon build-up usually requires a longer period of directed training to, in Pfitzinger's words, "provide enough time to do the volume, cut back a bit and introduce higher-intensity work, do a couple of tune-up races, and taper." Pfitzinger specifically trained for 20 weeks before his 1984 Olympic Trials race, and 19 weeks before the Trials in 1988. Other coaches, such as Arthur Lydiard and Bill Squires, suggest that a six-month period of preparation is optimal.

In any case, be sure to plan your tune-up races well in advance to help ensure staying on track, and remind yourself daily exactly where all of your energy investments are leading.

(This advice originally appeared in the July/August 2000 issue of Running Times Magazine., including the title and subhead, but not including any of the above photos.)