Recalling a pair of determined and serious track people from the days of disco and hair metal respectively

The mustier I become, the more digging into the dustbin of track history fails to get old

At last weekend’s 2024 New Hampshire Division 1 Indoor State Track and Field Championships, Anika Scott of Bedford broke the girls’ state indoor long-jump record by an astonishing 21 inches with a leap of 20 feet, 3.25 inches. In drone-striking the record of 18’ 6.25” set in 2012 by Hillary Holmes of Exeter into smoldering ruins, Scott became the first girl in state history to clear nineteen feet indoors and twenty feet under any conditions.

Scott, a junior, also moved from well outside the national top fifty into the number-three spot in the U.S., at least according to Milesplit’s conditionally reliable database.

Scott had already jumped one inch farther than the record in a league meet on February 3. But in New Hampshire, as with most places, state records can only be set at state-championship meets or other meets with similar levels of sanctioning, such as the 600-meter time of 1:19.41 Hanover’s Russell Brown uncorked at the 2003 New England Indoor Championships.

Two girls in the history of New Hampshire girls’ track have cleared nineteen feet outdoors. The first to get there was Bree Robinson of Pinkerton Academy, who soared 19’ 4.5” at the 2008 Division 1 Championships. (That same weekend, at the Division 2 State Championships, Dwight Barbiasz of Milford became the first, and to date only, New Hampshire boy to clear seven feet in high jump, reaching 7’ on the nose. Barbiasz set the still-standing state record of 7’ 1” the following week at the 2008 New Hampshire Meet of Champions.) The second was Coe-Brown Academy’s Ariel Clachar, who at the 2015 Division 2 State Championships recorded a best mark of 19’ 2.75”.

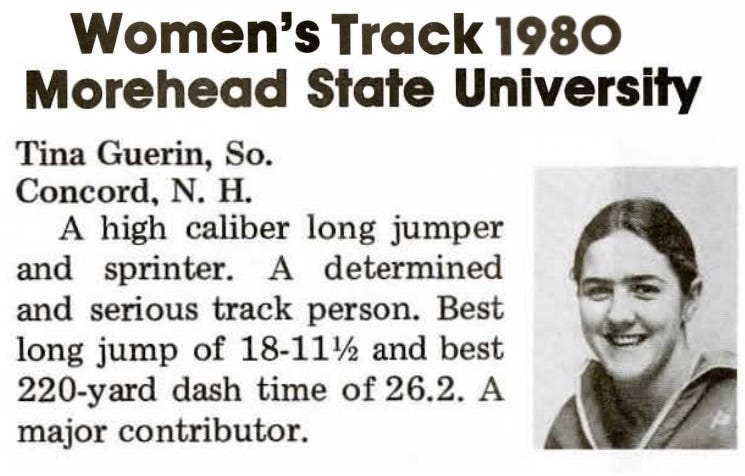

The record that Robinson broke in 2008 had gathered a thick layer of dust. In 1977, a Concord High girl named Tina Guerin jumped 18’ 11.5”, and for over thirty years no one came especially close to that standard. Despite exiting high school close to forty-five years ago, Guerin remains the fourth-best girl long jumper in state history.

Guerin graduated from Concord High in 1979, when she won her second straight state title in the indoor pentathlon, a since-retired set of events. This was nine years before I graduated from the same school. But despite Guerin’s name featuring prominently in the school’s trophy case in the track-and-field section while I was there, the only thing CHS types seemed to remember about Geurin is what a remarkable basketball player she had been. And while it’s true that Guerin was a member of the New England College women’s basketball team in the early 1980s, before that, she achieved the label of “a determined and serious track person” while enrolled at Morehead State University.

I’m unsure what led me this week to recall another amazing feat from well before the turn of the twentieth century, but one of the best high-school distance runs in the history of the Western Hemisphere remains curiously and unjustifiably obscure.

In the spring of 1987, a Canadian runner from Dundas, Ontario named Greg Andersen ran 8 minutes, 0.2 seconds for 3,000 meters at the OFSAA (Ontario provincial) Championships at McMaster University. This set a North American record, breaking American John Trautmann’s mark of 8:05.8 from the previous year. (Trautmann, whose near-certain ascendancy to the top of the American 5,000-meter ranks in the early 1990s was curtailed by injuries, is perhaps just as well known today for running 4:12.33 nine years ago this month at age 46 to set the world record for 45- to 49-year-olds.)

Despite being alone for the final kilometer, and arriving at the 2,200-meter checkpoint in 5:59-point, Andersen scorched his last two laps in close to two minutes. He had been on “only” 8:11 pace until that surge, so how much faster he could have run spans a wide speculative range.

Andersen’s area record stood for 22 years, until American (or at least Californian) German Fernandez clocked a 7:59.82 3,000-meter split en route to an 8:34.40 two-mile at the 2008 Nike Outdoor Nationals. By then, American Galen Rupp had taken over Trautmann’s U.S. record in the event by notching an 8:03.67 in 2004. Fernandez is now #4 on the all-time U.S. absolute 3,000-meter list and still has the best outdoor time, with Nico Young’s indoor 7:56.97 now leading the American, North American, and Californian-American all-time lists.

Andersen, like many top Canadians over the years and especially in the Vin Lananna days, went on to Dartmouth College. Andersen ran 13:49 for 5,000 meters as an Ivy Leaguer and graduated with an engineering degree, but failed to rise to the level his high-school exploits portended. (At the time, Ontario high-schoolers were required to attend a Grade 13, so Andersen was a little older than most American high-school seniors. But still.)

In 2020, someone with the aim of discovering what had become of Andersen since high school managed to track him down and interview him, with the result a long-form article on a now-dormant Substack site of which I was previously unaware. The piece noted that Andersen struggled with injuries as a collegian and was ready to quit running and start working when he graduated in 1992, and also explained that Andersen had moved frequently and kept a low public profile.

I was occasionally trained with the Dartmouth teams in the mid-1990s, by which time Lananna was gone, replaced as the Big Green coach by the estimable Barry Harwick. On lazy runs around Hanover, I heard some stories pertinent to Greg Andersen’s collegiate running and experiences. Some of these were extraordinarily colorful and undoubtedly explain some of the reasons Andersen never quite became a collegiate superstar. There’s no value in passing along these rumors now even if I believe all of them, but it’s safe to say Andersen was regarded as a demigod by some members of the program and at least sui generis on multiple fronts by others.

I have one other vague connection to Andersen. In August 1995, I ran a hilly 5K in Andersen’s hometown of Dundas as part of a cactus festival and won myself a prickly plant for winning my age group in 15:40. I was forced to leave this ornate but smelly prize in Toronto with my then-girlfriend out of certainty that the plant would be detained at the U.S.-Canada border. For precisely the same reason, I very nearly put in in my carry-on before heading to Lester Pearson Airport.

(Note: This article was edited moments after its publication to reflect the author’s newfound ability to distinguish the horizontal jumping events from the vertical jumping events in track and field.)