Recapturing the origins of my devotion to running using a virtual trip through time and space

Who needs video games with free online bushwhacking and trespassing tools?

Before I started running at the start of ninth grade in 1984, I already had a habit of exploring sizable patches of land on foot. I did not consider this “exercise”; no kid with access to a vast swath of largely undisturbed woods ever does, especially when he is, say, ten or eleven.

As I’ve mentioned regularly over the years, I lived for most of my childhood in a duplex modern log-cabin home situated on nine acres of swampy acreage on the outskirts of Concord, New Hampshire. My maternal grandparents, both nearing retirement, had the house built in 1978, and my grandparents, my parents, my sister, I, and our dog Wendle moved from the duplex my grandparents had owned in the south end of Concord to the new digs. Almost from the time I was born until I left for college in Vermont, and at points thereafter, I lived within a yell of one of my grandfathers while never meeting the other at all (my dad’s father died when my dad was 16 or 17). On average, then, I saw all of my grandparents somewhat regularly.

The grandfather I did know worked for the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department as a dispatcher and had a trove of U.S. Geological Survey topographical maps I discovered one afternoon when I was around nine while digging through boxes in the attic. I don’t think my grandfather ever used these, or even knew how to properly use them. I, on the other hand, had developed a fixation with maps when I was at most four or five, memorizing all of the streets in Concord with a bland obsessive glee bordering on autism.

This was a new, complex kind of map, rife with possibilities. I found the one with the “quadrangle” including our region and discovered it had been “culture revised” in 1957. Interstate 93, which runs less than a mile parallel to that log cabin on Mountain Road, was not yet built but as part of the newly unfurled Eisenhower Interstate system—among the most ambitious and triumphant infrastructure projects in American history as well as its most city-blighting and polluting—and was shown as a set of red lines. I saw that in the twenty-plus years since the printing of the map, many of the roads in my area had been discontinued, some because the interstate had bisected them, others because they had fallen into disuse thanks to the progressive irrelevance of certain farms or land transfers resulting in homeowners who had chosen to block off these Class V and Class VI roads crossing their property rather than allow vehicles to pass.

I did not understand all of these factors at the time. I just knew that time and people changed the land, but that there was a certain indefinable allure to finding things like forsaken, cracked roads, pre-World War II truss bridges with missing spans, or even ancient, abandoned houses that had become no more than open basements in the woods. And I had a map that showed an amazing amount of detail compared to a regular street map—where woods where versus open grassland, streams large and small, and of course elevation contour lines.

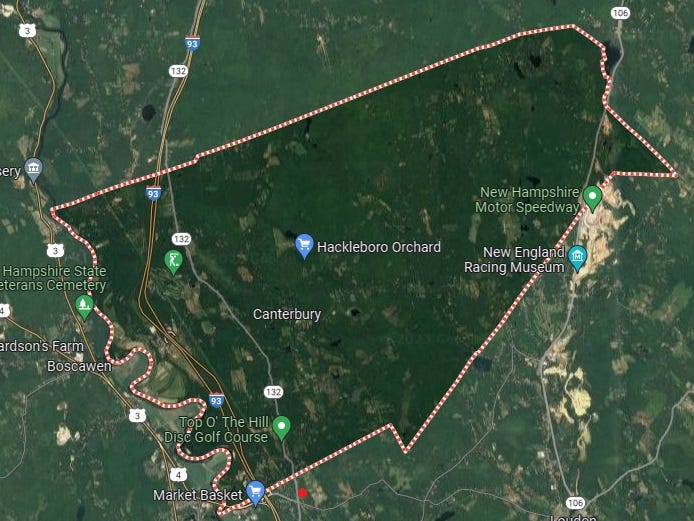

When I started running, it meant that I could cover a lot more territory than before. While I did most of this on standard roads so that I could measure the distances of my routes, the bulk of the land I explored in this way was in the town of Canterbury, which using one style of 2023 map looks like this.

In 1980, Canterbury had about 1,500 people crammed into its 45 square miles of hilly, boggy land. That number has since exploded to nearly 2,400. The position of the log cabin is depicted by the red dot near the bottom of the map. Most of its roads were not paved then, and at last notice, the ones that were had not received a fresh coat of asphalt since the late 20th century.

When I would prepare to do runs (which often became hikes thanks to unanticipated obstacles such as overgrowth and streams too robust to wade across) in parts of Canterbury I only knew from a map—and sometimes, I carried one with me, but preferred to rely on my imperfect memory—I did as much research as possible into whose land I might find myself on. Trying to correlate a portion of woods a mile from any road with a given house (these were, and still are, signified by small black squares on topo maps) was impossible because there was no telling where the property lines were.

One saving grace was that Canterbury, being a small New Hampshire town, includes an abundance of snowmobile enthusiasts, or did at the time. Trails used by snowmobilers in the winter and criss-crossing the town were perfect for running on in the summer, except for all of the horseflies and deerflies and other airborne mini-carnivores; landowners were generally accommodating of these—after all, many of them owned snowmobiles—and so were unperturbed by the sight of a far quieter trail-user in the off-season. And I knew that if I found myself confronting a suspicious landowner, I could just use the fact that I was a minor to my advantage and not only plead that I was lost (often true) but beg to use a phone to call my mommy to come get me.

I don’t recall ever getting the stink-eye from townies; I knew the one cop, who may still be on the force, and exchanged waves with him all over the southern portion of his bailiwick. In the late fall, thanks to the noises created by my shuffling passage, I sometimes got glares from hunters, who in turn got glares themselves.

Several night ago, I recalled running numerous times to the end of one L-shaped dirt road in Canterbury, near a spot I once went camping and cigar-smoking with a few of my snowmobile-owning friends, without ever determining if I could follow a path northward beyond the dead end to connect with the southern end of a different dead-end road a mile or so away up a considerable hill. For whatever reason, probably not wanting to make a scene, I had never attempted that search for an abandoned carriage road from the late 1800s.

Without even thinking about it the other night, after that road randomly came to mind, I started Google Earth, then opened tabs to TopoView, Google Maps, and the Town of Canterbury property-tax maps. Before long, I was reading minutes from the meetings of the town’s enthusiastic conservation committee and other public gatherings.

Using these tools, and employing various satellite-image angles, I figured out that, at least today, I could have made that trip and not caused any issues. Someone who owned over sixty acres donated or designated almost all of it as a recreational easement in 2017 or so. Because most landowners in Canterbury own a lot of it, or for independent reasons, they as a group seem to be behind the idea of keeping as much land available for benign public use as possible.

Also, because TopoView has maps for a given area dating back in some cases to the early 1900s, I figured out that I could have made the same foot-trip c. 1980 no matter who owned the land then, because there has always been a small easement connecting the two dead-end roads. This wasn’t obvious c. 1980 because the two dead-end roads had already been decoupled for decades.

The point, if there is one, is that I did a good deal of research back in the day when preparing to combine running with recreational trespassing for the sake of recapitulating local land-use history. But what I can do now, sitting in one place and pushing buttons, is truly incredible. It’s not just the level map detail but the availability of public records and civic proceedings. I can almost go running in a place two thousand miles away while lying in a recumbent position, and I can investigate both who most of the interested parties I might encounter in an on-the-ground version would be and what their attitudes about seeing a runner (with or without a dog) scampering across the far reaches of their property might be.

There is a flip side to the kind of people a tiny town like Canterbury tends to attract: They are Yankees, and they don’t trust changes to small town, especially those wrought by outsiders. On the map above. you can see an attraction called Top O’ the Hill, a disc-gold course. Less than a mile from the log cabin (now a group home for special-needs adults, just as the Bible foretold), this place opened six or seven years ago. I read the minutes from the zoning ordinance meeting for this place, and it was clear that the locals must simply have not liked the guy who wanted to install the course. There were residents of a dead-end street hundreds of feet away who complained about the clanging noises the discs would make when striking the baskets. Someone else wanted to build a four-dwelling residential building in the same area, and a multitude of locals rose up to express concerns about excessive urbanization and disruption of the water table. Both projects went through, and the woman who oversees the zoning stuff, a runner, likes to entertain guff like this and then shoot it down with feigned patience. At least that’s the sense I gain from reading the minutes.

Every town has citizens with these concerns, and many are valid, especially in a tiny place aiming to avoid any specter of urbanization, if not urbanity. It’s just funnier when you can visualize the geography and know that the complainers are full of it. I felt like somehow appearing at one of these long-concluded meetings and telling the whiners, “Well, your friggin’ house [pointing] wasn’t there when my family moved up the street in 1978, and neither was yours, yours or yours [pointing, pointing, and pointing again], because there lay a patch of excellent sledding woods for me and my homies that became a colorless subdivision. And now there are more. There are McMansions along Hayward Brook, where I used to go inner-tubing. So learn to toss a frisbee and appreciate what you have, like I always do.” (Mic drop optional.)

The fact that I spent so much unplanned time on this exercise—and I was utterly absorbed in the task—gets at why I fundamentally enjoy running so much and, given how little of the planet’s land I have actually seen, always will. I was decent enough at it for a while to be obsessed mainly with improving my times, but only genuinely competitive people, those who simply love racing for the same often ineffable reason I love maps, manage to keep that up into their dotage with as much vigor as a teenager.

I still don’t think I will ever get on an airplane again. But if I do, and it goes in a mostly east-northeast direction, there is a particular hilltop farm I want to check out. I wouldn’t fly across the country to do it, but if already there, well. And a few of you might just be maniacal enough about maps and familiar enough with Canterbury to figure out exactly the strip of land and the roads I’m talking about. If not, you have your own mysteries along similarly whimsical lines.