Rewarding decades of progress, USATF drops the women's Olympic Marathon Trials qualifying time to 2:37:00

The only victims of reasonably sized race fields are mediocrity merchants representing a narrow but noisy slice of the running population

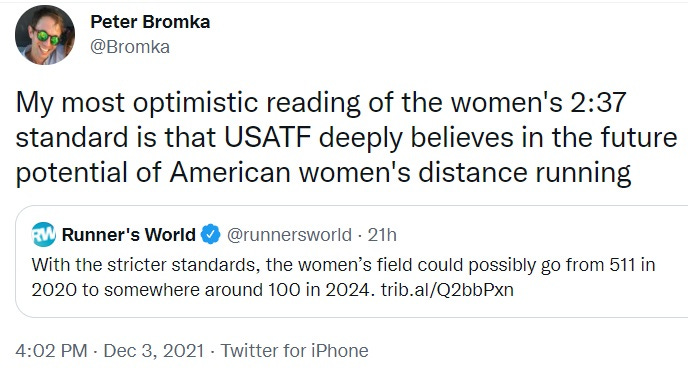

Yesterday, USA Track & Field announced the men’s and women’s qualifying times for the 2024 Olympic Marathon Team Trials: 2:18:00 and 2:37:00. That’s a one-minute tightening of the 2020 requirement for men and an eight-minute drop for women. Runners can also again secure a Trials entry with a half-marathon time, with the qualifying times of 1:03:00 for men and 1:12:00 for women being a minute faster than in the 2020 cycle.

Ultimately, the most significant effect of these changes will be improving the race for people with a meaningful shot at reaching the Olympics. It will also save USATF a lot of money, sparing more of it for the excesses of its officers.

The most noticeable immediate effect, of course, will be complaining from people whose motivation is twofold: One, many were raised to believe that participation amounts to excellence, and are thus determined to not accept the obvious reasons to limit the size of an Olympic Trials race; and two, they benefit directly or indirectly from softer qualifying standards. Self-interest is, after all, the basis for any negotiation, however crude its orchestration.

These voices are prominent on social media, but it’s clear that the interests their complaints are meant to advance are not held by the overwhelming majority of everyday runners, few of whom host podcasts, write for running-media outlets, or have even heard of the Olympic Trials Marathon.

A few facts:

The new qualifying times remain considerably slower than the 2020 Olympic Games qualifying standards of 2:11:30 and 2:29:30. Runners who can manage 2:18:00 and 2:37:00 on their best day are used to thinking of themselves as elite, but these have not been world-class times for years, the beliefs of a smattering of American mzungus notwithstanding.

As an on-fire-lately Sarah Lorge Butler notes, had the current standards been in place in 2020, a total of 258 runners—169 men and 91 women—would have qualified for the Olympic Marathon Team Trials. 258 total qualifiers for the 2024 edition would represent a sharp reduction from the recent past, but that does not make such a figure insufficient.

In 2004, 207 runners—58.5 percent of them women—started that year’s pair of Trials races, which had qualifying times of 2:22:00 and 2:48:00. Two of the 177 total finishers, Meb Keflezighi and Deena Kastor, won Olympic medals that summer.

In 2020, 681 runners—57.5 percent of them women—started the two corresponding Trials, the qualifying marks this time being 2:19:00 (or a 1:04:00 half-marathon) and 2:45:00 (or a 1:13:00 half-marathon). Of the 565 total finishers, one, Molly Seidel, became an Olympic medal that sum…uh, the next summer. And it was goddamned well worth the wait.Among the 2020 non-finishers was top-ten hopeful Kaitlin Goodman, MPH, who went to the pavement in a two-phase tumble within minutes of the start. Goodman tarried on to the halfway point, where she conceded she was too banged up to sensibly continue. At least five other runners fell during their Trials races.

I have lots of thoughts on the new Olympic Trials marathon standards announced by @usatf. Loved the amazing strength on display with 500 women racing in Atlanta, but the field size was too large for the start/1st mile - it was WAY too crowded. What’s the magic number of athletes?@stocktonprof The ultimate aim of the race is to select the Olympic team. So there's that. Also, someone like @runnerKG got tripped and trampled in Atlanta and she had a very good chance to finish top 10. It was just too crowded. That said, it's a powerful race to connect the elites...

I have lots of thoughts on the new Olympic Trials marathon standards announced by @usatf. Loved the amazing strength on display with 500 women racing in Atlanta, but the field size was too large for the start/1st mile - it was WAY too crowded. What’s the magic number of athletes?@stocktonprof The ultimate aim of the race is to select the Olympic team. So there's that. Also, someone like @runnerKG got tripped and trampled in Atlanta and she had a very good chance to finish top 10. It was just too crowded. That said, it's a powerful race to connect the elites... Sarah Lorge Butler @slorgebutler

Sarah Lorge Butler @slorgebutler

Consider not just runner safety but also the comparative logistical simplicity of races with, say, 100 runners each. The reduction of aid-station chaos alone on a multi-loop course is, almost by itself, a solid argument for smaller fields than 2020’s.

But set all of the many inherent problems with large Trials races aside.

The Olympic Games are chiefly about achieving the highest degree of excellence within a sporting discipline. The bar for excellence in all disciplines always keeps moving in the same direction, and more measurably so in running than most. If the U.S. does not move its own bar for the determination of excellence along with it, the result will inevitably be a growing number of runners in Olympic Trials races. Quite apart from logistical considerations, this at some point introduces unmanageable tension between what used to be great and what is now merely good.

The need to continually exclude faster and faster runners from the Trials, especially women, is a sign of basic progress. Having more runners under given sub-elite time barriers is also progress, but of a more distributed sort. It should be of greater interest to genuine American running fans that the ante for laying a legitimate claim to elite running status keeps getting upped, and that the U.S. keeps producing faster and faster distance runners at the peak level, some of whom avoid doping bans.

On the matter of the impressive glut of sub-elite American marathoners, it's funny how the changes to the standards between 2008 and 2020 (2:48:00 to 2:45:00 and 2:22:00 to 2:19:00) incidentally introduce an approximate correction to the degree of improvement in shoe technology. The tightening of the standards actually happened before “supershoes” became available, and even if one assumes the shoes give everyone who wears them a maximal boost, it's simply true that more runners are becoming very good, if not necessarily great, marathoners.

Because the new standards are likely to result in significantly more male than female qualifiers, it’s worth a look at how 2:18:00 and 2:37:00 objectively compare.

The difference between the men’s and women’s qualifying times has now been narrowed from 18.70 percent in 2020 to 13.77 percent.

Comparing this to the far smaller 10.21-percent gap between the men’s and women’s world records (2:01:39 and 2:14:04) and the minuscule 9.30-percent difference between the half-marathon world records (57:31 and 1:02:52, both set this year and neither yet World Athletics-ratified), it seems like that 13.77-percent margin, while more than halfway along the journey from 18.7 to 10.2, will be insufficient to satisfy strict M-F equality police. I mean, we’re talking about the most elite running platform in the world here. Why not have qualifying standards of 2:18:00 and 2:32:00?

I’m kidding. A reductionist “The Trials are all about picking Olympians” argument leads rapidly to simply setting the Trials standards at the Olympic standards (2:11:30 and 2:29:30) and having maybe two dozen athletes in each race. That seems to be erring on the side of extreme conservatism. After all, every lead pack benefits from a smattering of runners who stand no chance of being in the hunt past 30K or even halfway. A marathon time of 2:18:00 correlates nicely with a 1:05:45 half, just the pace needed for a 2:11:30. And a runner who can manage 2:37:00 should be able to run the 1:14:45 half-marathon that similarly dictates 2:29:30 pace. You may say, “People don’t train to run the Trials as pace-bunnies and sacrificial lambs,” but look at how many qualifiers wind up doing just that, cycle after Olympic cycle.

Still, most of the voices in the running media would much rather err, admittedly, on the side of fostering dreams.

Roche’s basic shtick seems to be substituting sunshine and rainbows for the necessity to make sense. Sadly, not having a mean bone in your body is scant compensation for having no pertinent thoughts in your head.

It’s interesting how many of the same people who claim that running needs to become more diverse and inclusive also want to keep the Olympic Trials bloated, when the major beneficiaries of a soft standard are white people just out of college living on some combination of external (parental or spousal) income and a part-time job. There is no harm in “living the dream” if you can swing it. But how, exactly, is a larger Olympic Marathon Trials supposed to draw, say, the urban (and rural, for that matter) poor into distance running? This is a stated priority of a lot of today’s running pundits.

Observers stipulate that the Trials are perfectly positioned to serve as a tangible bridge between world-class runners and Everyjogger. (At some point, a theory seems to have coalesced around the idea that more contact between elites and people who couldn't care less about elites makes citizen running both bigger and better.) In one of her tweets, Lorge Butler asserts of the Trials, “it's a powerful race to connect the elites.”

In reality, even if the Olympic Trials could serve this "bridging" purpose without detracting from its stated purpose, there is no evidence I am aware of that people sniffing elite or sub-elite status in running widely serve as envoys for anyone besides themselves and their demographic peers.

That's also fine, but it is what it is, and people tend to negotiate for what they themselves want most even while dressing it up in "greater good" language.

A larger Olympic Trials means more to talk about for more people trying to make a living from or an impact on running. "This part-time locksmith made the Trials despite having too many Coldplay CDs for a mostly self-respecting man” and "This woman can still run 6:00 pace despite the rigors of a pole-dancing lifestyle" make for interesting but clearly discretionary reading, and sharply reduced Trials fields may make some of those kinds of stories disappear from public view.

So think of many of these folks not as pontoons in a bridge, but as barnacles on an otherwise elegant watercraft.

That’s overly harsh, because most people who root for bigger Trials have at least thought about the issue somewhat broadly or deeply. I tend to give excessive weight to stuff like this, even while myself advising that these are minority views, propelled by the small but prominent number of individuals who don’t mind any costs to others—I’d bet Peter Bromka has heard of Kaitlin Goodman—as long as they see benefits for themselves.

A missed opportunity for whom?

Bromka is the co-author of this plea from last October to permanently bloat the Olympic Marathon Trials to absurd levels. In his spare time, he also enjoys repeatedly just missing the Olympic Marathon Trials standard at an impressive age, defending convicted dopers, and spelunking in his own arse. I evaluated his plea, along with Alison Wade’s call for large Trials published just before the 2020 edition, last winter.

I’ll say the same basic thing now as then. I understand that people agitate for things they want under the aegis of some, usually fanciful benefit to others. Such maneuvering is not evil. But when it reaches certain heights of dramedy, I can’t help but waste over fifteen hundred words and most of a morning on chiming in on how funny it all is.

I will expend a few hundred more on a real idea. Fix the number of competitors who qualify for the Trials, rather than relying on fixed time cut-offs. And fix it at 100 men and 100 women. Maintain a public list—these are easy to make and maintain, even if USATF is chronically slow to update their own—and at the end of every pre-Olympic year, name the 100 fastest of each sex during the qualifying period (probably two years) as qualifiers. In case the whole country starts to give up on serious road running, maintain certain minimal time standards—say, 2:18:00 and 2:37:00—to ensure full 100-runner fields in both races.

Have the Trials in midwinter or early spring, as usual. Everyone will know in advance whether they have to run a December marathon just to get in, and if those types can't recover in time for the Trials, this costs them but not the race itself, and no matter how their Trials races go, they’ll be happier to be among the Elite 100 than part of a mass of sub-whatever-whatevers.

This scheme would introduce an element of what everyone says running needs: Excitement. The real kind. And because it would focus squarely on bubble-people for a spell as the end of the year approached, the “sub-elites are world-class runners on extended bad streaks—read below for more” crowd can still be sated, to the extent this ever happens.

No one I know of who loves running has ever quit as a result of not making the Olympic Trials, and those who get in as edge cases rarely report their lives changing drastically as a result. The running media and meta-media will continue to thrive as well as they are now, given that they say and write whatever occurs to them, true or false, without consequence.

Finally, if you don’t think a 100-or-so-person marathon race loaded with the country’s best runners would make for all the great spectating and interaction that far larger ones do, you’ve probably never watched one. This one had 108 finishers.