Rich Martinez, 1963-2020

He held on long enough to conquer one demon, if not all of them

I got the news late Tuesday that Rich Martinez, who as a senior at Widefield High School in Colorado Springs set the Colorado high-school boys’ 1,600-meter record in 1981 in Pueblo with a 4:10.98 that technically still stands, had passed away early that morning. He was 57.

The photo below is from last year.

While finishing a run with my dog a little after 11 p.m., I heard an incoming text from the hand not holding the leash. My phone is rarely with me when I run anymore mainly because my dog almost always is, but I’m between small flashlights, and a lit phone screen is sufficient to keep Rosie and I safe from what little traffic there is at that hour. Tonight, I did peek, at a red light about two minutes from home, actually figuring on a communication from a friend waking up on Wednesday in Phnom Penh. It was from Richie’s girlfriend, and what it said was a surprise-not-surprise.

Richie is the friend I spent last Christmas with, experiencing challenges I was ready-not-ready for.

I read the one painful paragraph in the text, standing in the dark at an empty intersection where I was needlessly waiting for the light to change, then started running and crying at the same time, which may be a first and is not easy to do at all, without cheating, even moving slowly, with or without a really good reason. I think if you saw someone doing it, with or without a dog, you would assume something beyond ordinary sadness was at work. But that’s all it was, because real, acute sadness is one of the more extraordinary things a normal human ever experiences. It was a confusing two-minute shuffle for Rosie, I think, but she always seems to tune in and adjust in style to whatever oddities I present.

Years ago, Richie and I were occasional drinking buddies. Both of us know neither one of us was supposed to be anywhere near alcohol, so these at gut level weren’t fun excursions, just sloppy men becoming more gross in their dubious element. If I went descriptively even half-deep into some of these unlikely experiences, they would read like bad attempts at bum-fiction. Whatever aspects of these seemed funny in the time since, which really wasn’t much anyway, no longer does since only one of us is around to laugh.

Richie, for reasons I may never fully understand, was incredibly loyal to me in every way. He was utterly supportive of me giving up drinking in 2016, even if he could never string together more than a few game months himself. He never had much, but was always eager to give me something I didn’t have, whether it was a running watch he no longer needed or a signed number with a story attached. And as Richie spent a few years as a real figure on the national track scene, what he really contributed were some funny stories. One was from his days in the late 1980s training in Albuquerque, then more of an elite international mecca than either Boulder or Flagstaff is today, and encountering a Kenyan runner named Billy who started showing up at group sessions to do nothing, apparently, but stretch while everyone else busted out intervals. This went on for a number of practices until someone indicated that stretching Billy was Billy Konchellah, who had won the 1987 World Championships gold medal in the 800 meters. Richie swore he never really saw Billy do much running, but whatever Konchellah did between World Championships resulted in a second gold in 1991. The way Richie described other Kenyans in the group — among them two-time Boston Marathon winner Ibrahim Hussein — ribbing Billy and other Africans in the mix was the funniest aspect of these yarns; Richie, you could tell, was just happy to have been a part of all of that.

Since I last saw Richie just under a year ago, something happened that took a huge burden off his mind, and that was Cole Sprout running under his state record with a 4:07.2 time-trial in April. Whether the mark is officially ratified was, and of course now is, of no consequence to Richie, because to him, his record represented something of a reverse white whale: He couldn’t wait for someone to break it, bury it, in part because he was tired of his name coming up every spring when the Colorado State Track and Field Championships would roll around, but really because he just wanted to see someone deserving succeed. He remembered well how it felt to have that quiet power, even if had eluded him for decades. As it was, Richie had seen a number of candidates primed to break the mark be stymied by the multi-day format of the championships, obligating most star runners to run one or two events before the 1,600 meters on the third and final day. He’d been in touch with a number of them to encourage the quest, including Cole.

Richie and I spoke on the phone after the 4:07.2, and if relief mixed with beatification can travel intact through a 5G network, it did that day. Cole’s own high-school coach seems to have had a hard story of his own, and though I don’t know anything more and wouldn’t tell it if I did, this seemed to draw Richie even more into Cole’s corner.

People who knew Richie Martinez from only message boards knew him as a standout-turned-skid-row story, someone who deserved sympathy but was basically the sum of some fast races and the hard times that followed. As is usually the case, but in a more pronounced way here, Richie’s path was a lot more complex than the grip booze had on him explains. I don’t think he ever got adequate support for other issues he had, and he was by his own admission very stubborn about this, about maintaining agency and autonomy at every possible step. I hope everyone is sanguine enough about basic humanity to understand this.

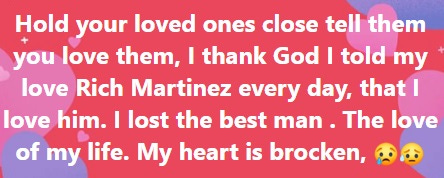

His girlfriend left this Facebook message on Tuesday night. She was with him through a lot and vice versa, and I’m glad she has her own family around right now.

Elsewhere:

I have a couple of long posts inching toward completion, one about the most recent issue of Runner’s World that uses its inclusion of one of my mustiest Running Times articles as a Trojan horse for bitching about a host of other things (though I may have just blown that strategy apart) and the other concerning the grotesque escalation in tactics and shrillness of the already powerful and despicable local Karenhood chapter since COVID-19 struck. It’s not unusual for me to be waging multiple online battles at the same time; as the kind of lovely soul whose life is incomplete unless riven with public philosophical battles, I have largely abandoned my focus on the religious right in favor of targeting SJWs and “pro-science” Boulderites who seem to think viruses have tiny bat-wings and bat-radar. But it’s unusual for me to have so little overlap in the batches of people I’m arguing with, or at least writing words at. I can spend fifteen minutes on Nextdoor pointlessly defending the bare-faced, socially distanced elite runners yonder from a small but dedicated coterie of screeching ignoramuses, and then immediately shift to re-exploring in a blog-post draft the various reasons that organized running ought to be put out of its own misery, or at least not taken at all seriously by outside observers.

My reluctance to finish these posts hasn’t been rooted in a word-production malaise, or being too busy with other things, or anything other than not feeling quite up to adding the kind of goop to the conversation right now that I want to. I can’t think of a time when I have used external events as any kind of excuse to table a troublesome post, and it’s not as if I intend to excoriate anyone or anything unjustly or to excess. I think it’s more the idea that even some of the subjects I think deserve a solid panning at the moment can wait to see how ugly things become with strained hospitals and such in the next six weeks.

That resolution came even before I heard about Richie, and that was less than three hours ago. And as usual, I have no fucking idea what happens next, only that I keep managing to show up for it. And that, starting now, is going to be a great deal of manageable grief. I have people I can talk to who do understand the tragicomic aspects of Richie’s life and my intersection with it, and I know where to find them. And I know when I get to talking about Richie and who he was, on which running ultimately had little bearing when it comes to how I knew him, a lot of good things come out.