Ross Tucker on Eliud Kipchoge's training

The formula is the easy part. The (lack of) rest is up to you

Sports scientist and frequent Twitter-redeemer Ross Tucker wrote an article for Runner’s World this week breaking down the training of 2:01:09 marathoner Eliud Kipchoge. Although the title is “Here's how slowly Eliud Kipchoge runs 85% of the time,” the words in the page’s source code between <head> and </head> tags are “Eliud Kipchoge 80/20 training strategy explained,” suggesting that whoever responsible for the discrepancy either reads, once worked for, or will eventually work for Vox.

As the article’s visible title implies, Tucker focuses on the zoomed-out intensity distribution of the world record holder’s voluminous pitter-pattering (200 to 220 kilometers per week, about 125 to 135 miles per week), emphasizing that Kipchoge—often compared to a slightly younger version of either God or Miruts Yifter—basically jogs about five miles for every mile he covers with purposeful vigor.

The point of the article is to make it as straightforward as possible for readers to incorporate into their own training, permanently, the parts of Kipchoge’s workload that don’t require a professional runner’s free time, talent, external motivation, or undisclosed around-the-counter supplements.

Tucker does this well. The most important point he makes is that runners who don’t spend as much time on their feet as Kipchoge does can run a higher proportion of their total steps with purposeful vigor. This means these runners can shift Kipchoge’s 85/10/5 ratio of easy/moderately hard/very hard training to the right, doing as little as perhaps 70 percent of their running in “zone 1.”

Because the piece is in Runner’s World, however, Tucker’s “for example” is applied to someone running 30 miles a week. This wisdom needs to land on the many people out there who train a lot more than that and care enough about the outcomes of their races to organize their lives around running—even if most of them will refuse the central message of the piece, and many of the faster ones will also extract precisely the wrong one.

“We need to avoid the temptation of tinkering, and rather earn our physiological adaptations through disciplined repetition.”

If Eliud Kipchoge is running 15 percent of his mileage vigorously, and one-third of that subtotal really vigorously, then when you ignore his jogging, he’s running about 20 miles a week. This is a lot, and if he could manage more, I’m sure he would, as he seems to enjoy running fast for extended periods, often on worldwide television.

This isn’t how Kipchoge does his 20 or so legitimate weekly miles, but for someone running a similar amount—say, myself twenty years ago—those could consist of a 9-mile tempo run or marathon-pace run embedded within a long run; six times a mile at 10K race pace with two- to three-minute recovery jogs; and 20 times 400 meters at 5K pace with short rest (around 45 seconds or 100 meters), along with sets of short, fast strides before and after the repetition sessions. The first two sessions combine to meet the “zone 2” “requirement,” while the quarters and strides supply the “zone 3” element.

One “omission” by Tucker is underscoring just how slow 4:30 to 5:00 per kilometer is for Eliud Kipchoge, even in Eldoret, which is about 6,857’ above sea level. (Tucker lists Kipchoge’s easy-run pace range as 4:00 to 5:00 per kilometer in his first reference to Kipchoge’s “zone 1” training, but if Kipchoge really does slow down to 5:00 per kilometer at all, it seems safe to go with the range Tucker subsequently supplies.)

The same effort range at sea level would yield paces around 5.5 percent slower faster, or 4:16 to 4:44 per kilometer. This is about 6:49 to 7:37 per mile, the midpoint of which is 7:13. Given that Kipchoge’s marathon pace is 4:37, he’s doing his “zone 1” training at an average of over 50 percent slower than a pace he can hold for two hours. And ten of his thirteen weekly runs fall into this category.

The actual figure is 56 percent (433 seconds/277 seconds = 1.563). But if we* cheat and assume 50 percent is fine, and apply that factor to some ordinary but still pretty fast marathoners, we quickly discover how slow this is. A 2:24:17 marathoner, for example, seeking to replicate Kipchoge’s methods would run his or her “zone 1” mileage at about 1.5 times 5:30 pace, or 8:15 pace. Someone capable of the U.S. Olympic Trials “B” standard for women, 2:37:00, would be doing 85 percent of her mileage at around 9:00 pace. A 2:55 marathoner would learn to love 10:00 pace. (For reasons not worth bullshitting about, the way heart rate declines with pace in a world-class runner may not map perfectly onto what happens in mid-pack runners, but 50 percent should work well enough for everyone.)

The reason you don’t see or hear of many runners doing this is because it’s rare; most runners have gotten to whatever ability level they can claim by doing things differently. The ones who learn that Kipchoge and others are training this way either refuse to trust that it will work if they try it themselves or, more commonly, just don’t care enough. They would rather allow for dick-around randomness in most if not all of their easy runs, which they distribute across multiple chaotic groups as if pursuing cheerful but crippling lack of discipline with uncanny single-mindedness of intent.

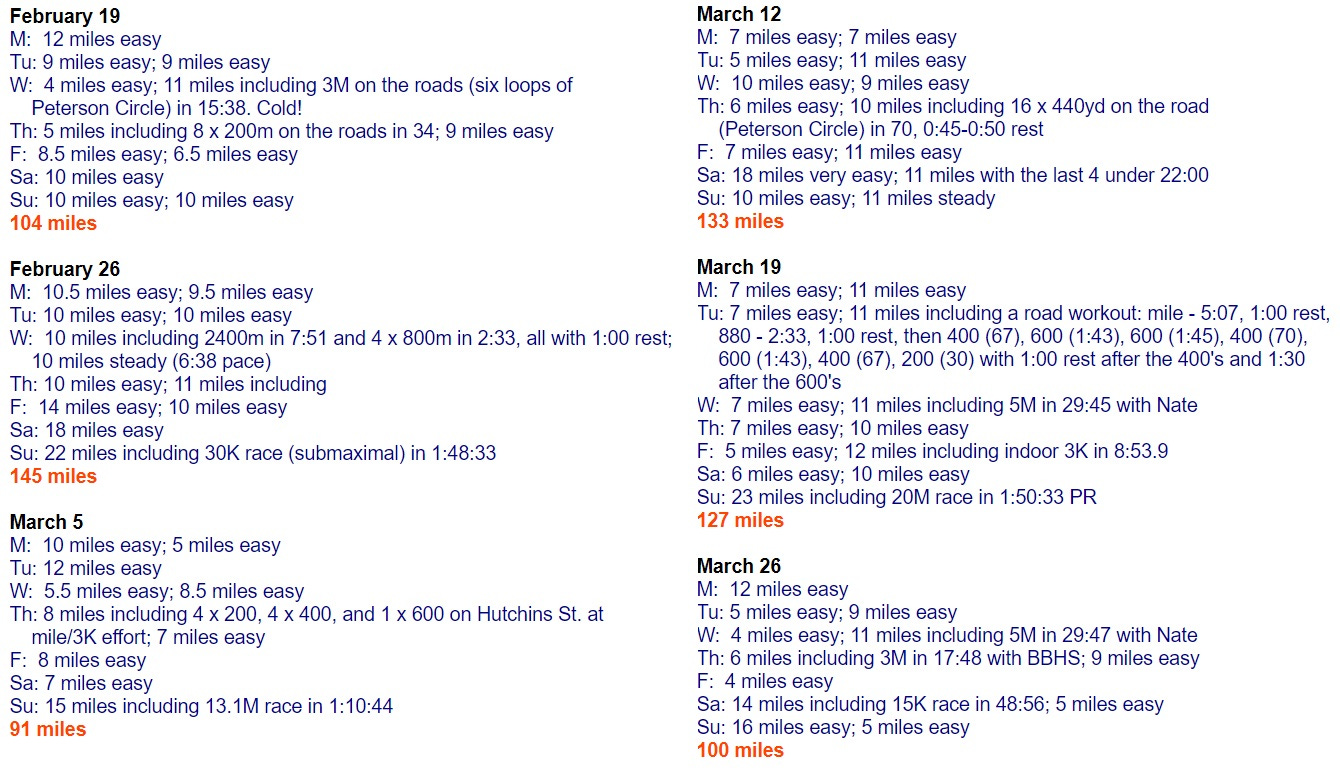

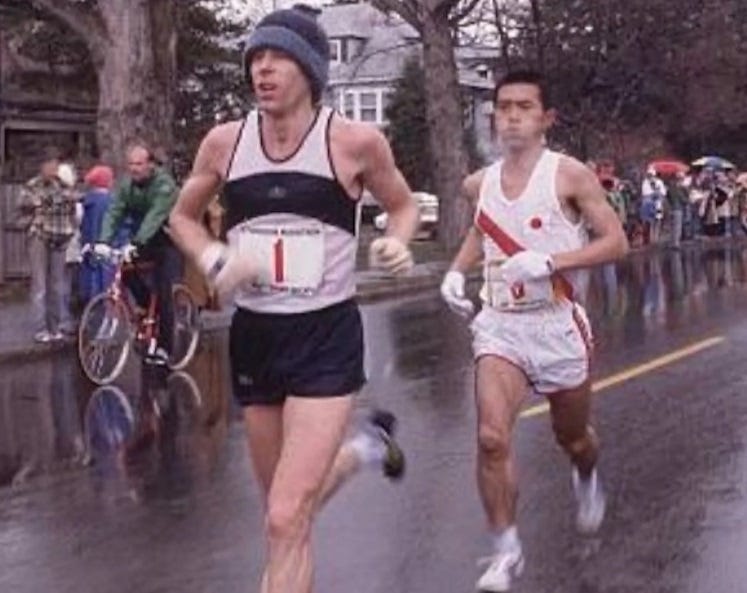

In 2001, I averaged about 113 miles a week in the three months before I ran 2:24:17 at the Boston Marathon, ranging up to a high of 145. I had been coaching high-schoolers for close to two years by then, and did a lot of my easy running with the teams. Except when participating in the kids’ hard workouts, this was all at around 8:00 to 10:00 pace (I was allowed to run with the girls at times, but usually gave them my yellow Lab). I would love to say I chose to start running so many of my maintenance mileage appropriately slowly by design, but alas, it was no more than a fortuitous consequence of my decision to work with those kids.

But once I lucked into this and realized what I’d done, I didn’t forget the lesson. After I moved away from New Hampshire and was no longer coaching kids, I began dating women with 5K PRs in the 19- to 22-minute range and dialed into the same general scheme, except that now I was—for months or even years at a time—listening to a single set of jokes, concerns, and farts on the go instead of a dozen, my own excluded.

It’s a good idea to have a regular training partner about one-third slower than yourself as long as you honor the fact that your partner’s “zone 2” and “zone 3” paces are as sacred to him or her as yours are to you and that he or she may not admit to you when things have gone a little overboard for his or her purpose, which has less wiggle room than your own in these situations.

Another issue I’ve seen is runners fast enough to replicate the easier parts of schedules like Kipchoge’s actually trying to reach Eliud Kipchoge’s level through this perverse-engineering of his fitness. What I mean is 31-minute 10K guys who see that Kipchoge is running around 110 miles a week at slower than 7:00 per mile, and go out and do 100-mile weeks consisting of 90 miles at 6:55 pace plus a couple of ill-conceived, in-over-their-heads workouts to complete the “mimicry.”

This is a failure to accept that Kipchoge didn’t cause his own fitness by running endless miles at that pace. That he can do so effortlessly is a consequence of his talent. And the lesson in Tucker’s article is that if you want to discover that you have a lot more talent in the marathon than you believe you do, especially after stagnating for a few years, then don’t spend all of your training time around faster runners or even fitness peers. Find people to run with who are so slow that they are incapable of letting you defeat yourself with your own “I’m an exception” thinking.

Finally, this isn’t a formula to follow for a 12-week training block. If you’re a dedicated long-distance runner, it’s something you should incorporate as an operating standard. And it’s not a new idea—Japanese greats, for example, have been doing this kind of thing for at least fifty or sixty years. Plenty of dedicated American runners I know purport to have plenty of long-term discipline, but unfortunately any displays of it usually crumble after a week, if that. Dedication and discipline aren’t the same thing, but it’s easy to confuse one for the other until conflicts arise.

The cold fact is that Kipchoge cares about one shiny object at a time, and it guides him. Most of us care about multiple things at once and become easily distracted by others. Nevertheless, his path toward his idea of the light is no more complicated than it ever was, and no one else’s needs to be any more complicated than his.