Runner's World has incidentally exposed more of the Roches' ignorance by replacing internally unpopular content with incoherent piffle

These people cannot help but beclown themselves, which is hilarious considering their entire lives are about impressing the cognoscenti

At the onset of 2021, the Runner’s World website included around forty articles with my byline, some of them over twenty years old. Runner’s World had inherited all but one of these from Running Times, which Rodale (the former parent company of Runner’s World) purchased in 2007. The lone exception, a story skeptical of nasal-only breathing, disappeared on March 29, 2021 and was replaced at the same website address by a completely contradictory piece.

It took me over a year and a half to notice this, and about another six months before I started asking questions about the change, focusing on two Runner’s World employees in particular. Receiving no answers to these questions led me to reframe them in increasingly creative and purposefully unwelcome ways. Again I got no response, but Runner’s World soon unloaded the rest of my content from its site. Perhaps they did so because I specifically invited them to. But admitting to this would mean admitting to reading the things I write about them, and that just won’t do at their end.

Only in recent days did I notice that an article about tempo runs I originally wrote in 1999—which piece Runner's World’s editors had already defaced for a grand 2018 repurposing—had been replaced in March 2022 in the same way my nasal-breathing article had, right down to Runner’s World sticking with the same URL while paving over what was there previously.

My piece had been deemed serviceable enough by Runner’s World editors as recently as 2020 to be singled out for inclusion in the November/December print issue despite its vintage. Yet now in its stead stands the kind of bland, self-contradictory pablum characterizing everything this publication now excretes. And just as with the magazine’s March 2021 maneuver, it took me around a year and a half to notice Runner’s World had done this.

As the mood strikes, I’m still asking questions of Runner’s World types about why they’ve done these things, as in my mind I am owed an answer. I realize that “the running media” has always been a term begging for “[sic]” to be appended to it, and that none of this matters to anyone. But I do enjoy mysteries and getting to the bottom of things, and these goons are not doing their part to help me here. And if these twits aren’t even going to become paying subscribers despite clearly reading all of the no-star reviews I give their work, than they can at least explain the nature of their grudge. Because that’s all it is, as understandable as it is that they don’t wish to admit it.

But my many other thoughts on that subject are currently incubating in a post draft that will melt most smartphones if it escapes and self-publishes before I can excise from this opus-in-progress some of its disclosures of animal sacrifices, plagiarized passages from white-supremacist beat poets, and mostly peaceful nude photos. So, this post will henceforth focus instead on the content of Chris Hatler’s March 23, 2023 article about tempo runs and how it underscores how the phenomenal laziness of David and Megan Roche, the founders of the popular-among-rich-dummies coaching-mill Some Work, All Play (S.W.A.P.) is in a constant race to the bottom with their lack of essential practical know-how.

First, Runner’s World has already subjected this dreck to a flim-flam exercise that’s become standard over the last decade for the dilapidated publishing industry: changing a story’s date every now and then to make it appear green at any time. Although Hatler’s article is nearly a year and a half old, the most recent version on the Runner’s World site is dated August 14, 2023. And this version is supposed to be available only to subscribers, something they should have thought of before leaving the piece open for archiving by the Wayback Machine for almost eighteen months.

As for the advice, I’ll only focus on the most blatantly unhelpful portions. Like this one:

You can determine your tempo pace without needing to calculate a bunch of numbers. For instance, legendary running coach Jack Daniels says in his popular book Daniels’ Running Formula that tempo pace is similar to how fast you can run for an hour-long race.

According to expert off-the-record sources, a great deal of goal-oriented running focuses on “a bunch of numbers.” An hour-long race takes approximately one hour. According to units, an hour is a measure of time; though fraught with inescapably ephemeral qualities, time can be assigned firm numerical values. For example, “one hour” is a time span equal to 3600 seconds or 60 minutes.

Another way to measure feel is following your rate of perceived exertion, or RPE.

RPE stands for rating of perceived exertion. It is a unitless number. If it were a rate statistic, it would have units of some quantity per unit time, such a miles per hour or photons per second. Had Hatler referred to a source other than Runner’s World itself for a definition, he might have discovered the correct one.

This is nitpicking, perhaps, but although I have known for years that the suite of Outside, Inc. publications have been operating a functionally editorless states for several years, I have retained more faith in the ability of Runner’s World to stay somewhat on top of the basics even when the publication’s greater mandate as an arm of the considerable Hearst empire, which it joined in 2018, is to intentionally churn out lies about covid, gender science, social activism, and the unholy mess in Ukraine. If ways to lie about aspects the 2024 election present themselves, that’s gotta be in the Runner’s World business plan, too.

Back to Hatler:

On a scale of one to 10 [RPE] helps you measure how hard an activity is, with one being a leisurely activity that you could do all day and 10 being your all-out effort which you can only sustain for a short time.

Megan Roche, M.D., an athlete, endurance coach, and clinical researcher at Stanford University, tells Runner’s World that a tempo run would likely be in the 4 to 6 range. RPE is completely subjective, though, so figure out what easy and hard means relative to your training, and find a place in the middle for your tempo run effort.

The original Borg scale for RPE, which ran from 6 to 20, was useful because it had a reliable real-world correlate: heart rate. Clinicians established that in large samples of subjects, as long as the subjects weren’t too old, the RPE numbers they offered stayed right around one-tenth their measured heart rates at the times of their spoken or wheezed reports.

Like the equally superfluous term “RED-S,” which means “undereating,” someone probably invented the newer scale merely to feel more important in the world. It has no reliable physiological anchors and would therefore be a useless tool even in expert hands. That’s why world-class non-expert Megan Roche manages to render the concept even more bereft of meaning.

If you flip a fair coin ten times, there are 1,024 possible outcomes. Nearly two-thirds of these ten-flip permutations include either 4, 5, or 6 heads (or tails). What, then, does advising someone to stay in “the 4 to 6 range” on any continuous scale of 1 to 10 add to any discussion?

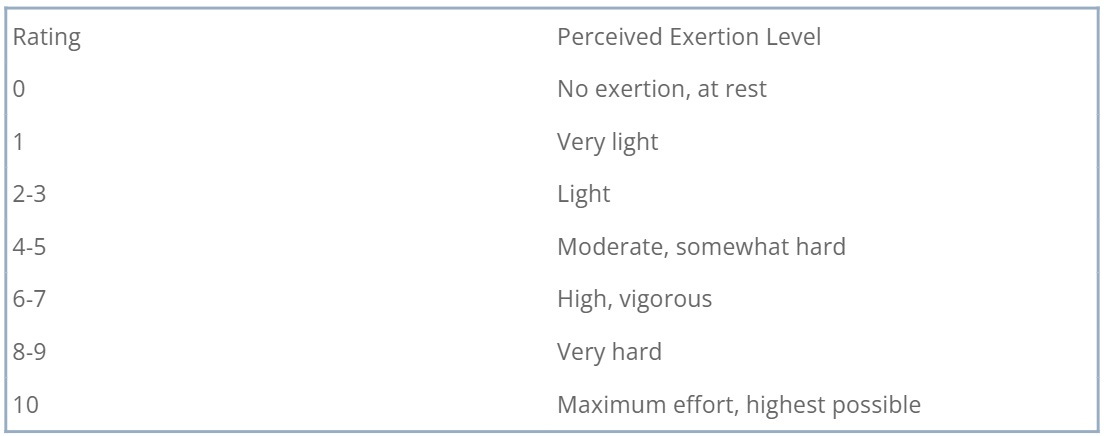

And according to the National Academy of Sports Medicine, here’s what the numbers on the newer scale translate to in terms of perceived physical effort:

So, according to Coach Roche, M.D., a tempo run is anything between light and very hard, with “vigorous” possibly on the edge.

Fortunately for the article’s readers, the article goes on to contradict this by offering some solid numerical references, some drawn from treadmill testing in a lab, others wrung from Apple watches. Unfortunately for the article’s readers, these don’t cohere very well, often because Jack Daniels goofed up in a few areas and every lazy writer likes to transmit all of Daniels’ published suggestions almost verbatim without vetting or updating any of them.

This line in particular stands out:

Tempo pace works out to be 90 percent of your max heart rate.

This level of exertion—and most people’s anaerobic-threshold heart rates are well below 90 percent of max, but forget that for now—is clearly at least an 8 on any reasonable 1-to-10 perceived-exertion scale. Evidently, then, a tempo run is pretty much anything you want it to be as long as it’s neither a jog nor a race and lasts at least 20 minutes. Except for those who are interested in numbers, which are relevant to performance only when people pay attention to them.

Between Dr. Roche’s loopy observations about running and her unscientific rambling about covid during “the pandemic,” it seems legitimate to wonder whether she secured her medical degree through legitimate academic prowess or whether this transpired as a consequence of keeping her professors happy in other ways. Sure, when she rolled out the “mask outdoors” advice despite being a trained epidemiologist, she was merely playing the anti-health role all proper physicians were playing when covid emerged. But she presumably has no incentive to sound like an idiot when discussing running physiology. Maybe trail-running coaches should leave concepts rooted in sustained, steady-rhythm running to the track and road-racers.

I used to think anyone who graduated from Stanford Medical School was unusually bright. I was accepted into the only medical school I applied to, and I applied early-decision to an Ivy League institution. But I never would have gotten into Stanford with my MCAT scores, and I had multiple classmates who had come east to Dartmouth after being rejected from Stanford (and in at least one case, even U.C-Davis). But Stanford Med probably has probably always left more room open for legacy admissions and other exceptions to the “ultra-high-performer” rule in Palo Alto than I thought; if not. perhaps it shifted in that direction sometime after the mid-1990s.

Or maybe shoddy thinking is contagious, with or without a mask on. As daft as Megan Roche often seems, she’s not nearly as much of a blundering meathead as her husband.

A few weeks before Hatler’s story was published, Trail Runner published a story by David Roche titled “Everything You Need To Know About Tempo Runs.” The more male of the two S.W.A.P coaches, in contrast to his wife, is a big fan of data. Near the top of the article is this (oomphases mine):

Lots of runners left to their own devices will think that the faster the tempo, the better the workout. A three-hour marathoner could probably do that tempo around six-minutes-per-mile pace in a hard effort. Heck, yeah, that’s a beastly tempo! But it’s probably not as productive as it could be.

Instead, based on traditional conceptions of tempo running, that athlete should be doing the tempo closer to 6:15 to 6:30 pace. Yes, this is one of those cases where slower and easier is better, and not just because it gives you more energy for some T-Swift air guitar on the cooldown. Let’s dig a bit deeper into that counter-intuitive message.

It's not hard to pin down a typical three-hour marathoner's threshold pace based on the "pace maintainable for one hour" definition.

This runner should be capable of close to 1:25:40 for a half, which is 6:32 pace, as well as 38:35 for 10K, which is 6:12 pace. This means that a three-hour marathoner’s 10K and half-marathon paces are roughly 20 seconds apart.

An all-out 10K and an all-out half-marathon represent vastly dissimilar subjective race experiences, yet Roche guesses that this person would be well served by doing tempos at 6:15 to 6:30 per mile. That's not only grossly imprecise by Roche's supposedly research-informed standards; heck, yeah, it's comically broad by any standard.

The point isn't that any given three-hour marathoner's actual threshold pace can be determined with absolute precision based on this information alone. It’s that "threshold runs" are supposed to be done in a very narrow pace (or effort) range. The word “threshold” does most of the work in the term “threshold run.” One of the jobs of a coach is to more closely pinpoint their athletes’ anerobic thresholds than they could do on their own, and monitor the evolution of same.

Roche also says that this runner could do a tempo run at 6:00 pace if desired—an option that, although “beastly,” is “probably not as productive as it could be” for such an athlete.

In reality, a three-hour marathoner would typically be capable of an 18:20-18:25 5K. That's 5:55-ish pace. This person would therefore be able to hold 6:00 pace for at most 25 minutes going flat-out on a good day. It's as if Roche took the "20 minutes at 60-minute race pace" idea and somehow got himself to "20 minutes at 20-minute race pace."

An even easier way to demonstrate the absurdity of Roche’s proposal: If a 3-hour marathoner can do fast, if “probably” suboptimal, tempo runs at 6-minute pace, then in general, an x-hour marathoner could perform these kinds of tempo runs are at 2x-minute pace. This would mean that Eluid Kipchoge, or anyone who’s close to a two-hour marathoner, could do tempo runs at close to four-minutes-per-mile pace.

Kipchoge’s fastest time for two miles is 8:07.39, and he ran that in 2012 when he was only in his mid-thirties. It seems that this section of Mr. Roche’s article, and whatever festering chum lurks below it, could use some revision. And maybe he should consult with his wife on this stuff, if only to keep him from engaging in computations that extend beyond the scope of counting to ten by integers.

Taking myself entirely out of this situation, and zooming out to the attempted perspective of a runner who has stumbled across the Roches’ media output, the existence S.W.A.P. of would strike me as impossibly bizarre. David Roche has a degree from Columbia Law School, and Megan Roche is a Stanford Med-bred physician. Although neither appears capable of reasoning themselves out of a sopping-wet paper bag, it’s a mystery why they decided to shuck (or in Megan’s case, downscale) careers corresponding to their degrees and the investment each of them put into earning those degrees. After all, clearly, these two are status-seekers. Yet for whatever reason, they decided to play the game they’re playing now instead.

And why not? They’re ridiculously wrong about everything that matters, and they don’t even agree when it comes to choosing useless or incorrect definitions of important concepts. But the game is plainly working anyway. None of the one hundred or clients they advertise having seems to have come to the realization that at this volume, and with only two coaches, no one client can expect to receive more than a few minutes of attention each month, except for the ones doing well enough to boast about on Instagram.

When anyone associated with the Roches gets upset with me for criticizing them, I don’t think this arises from a desire to legitimately defend anything this power-couple says or does. I think they hate being exposing as suckers, hypocrites, and intellectually barren status-seekers in their own right. These are some of the most pampered people in the country, and they can’t even handle a little recreational reality about an optional activity.

Either way, they’re the ones on a massive ship of cowardly and confused, yet resolutely arrogant fools. If they’re trying to tell me there’s no room for me even as a stowaway on such a diseased vessel, hell, I hear that. But I’m still going to offer regular assessments on how the voyage is going.