Slight variations in training mileage between groups of marathon runners are irrelevant when every group is severely undertrained

Still, there's a smarter way to look at these differences than Women's Running just did

“Strava Data Confirms Women Are Smarter Racers,” claims the headline of a November 21 Women’s Running article by Malissa Rodenburg. Even for an overarching attempt at sheer clickbait, the story is a mess, but it strays from sense and sensibility in such bluntly unsophisticated ways that it offers useful lessons to normies about how to not gather, interpret, or present numerical data.

Rodenburg claims that data from the accounts of time-goal-oriented runners who trained for and raced the 2023 New York City Marathon on November 5—data “released from Strava,” whatever this means—“identified why women may be more successful in reaching their race goals than men.” This seems to translate to “It’s uncertain whether either sex is significantly better than the other at achieving running goals, but if it one day turns out that women are better than men, we already know why.” This in turn is a lot like saying, “Maybe my guess will be right.”

But I think that the concept Rodenburg was aiming for was “may have identified why women are more successful in reaching their race goals than men.” If only someone at Women’s Running were being paid to look over these articles before they’re uploaded for public consumption. Perhaps managing editor Zoe Rom has been spending her work days scouring the Web for people to hire to attend to annoying tasks such as the granular editorial management of the publication’s articles.

Rodenburg:

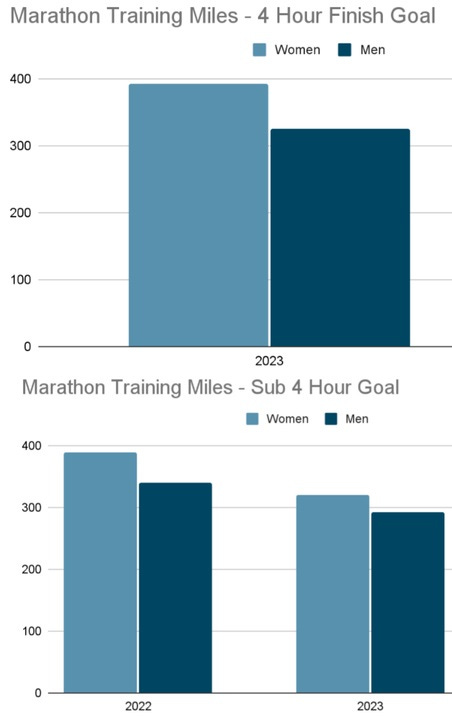

According to Strava’s data, for runners aiming for a four-hour finish, women logged 21 percent more miles across a 16-week training cycle. Women aiming for a sub-four-hour finish also trained more than their male counterparts.

The first problem here, and it’s a large and obvious one, is that Rodenburg doesn’t even reveal how many runners were included in the datasets she collected (or were “released” into her custody). If there weren’t at least a few dozen runners in each category analyzed, the results can’t be very helpful unless they show numerically stark and practically meaningful differences between groups.

The second issue is that it’s unclear what “four-hour finish” even means. Ordinarily this would seem a clumsy way of expressing “a finish of four hours or faster,” but Rodenburg already has a category for that—“sub-four-hour finish.”

So, does “four-hour finish” therefore mean exactly four hours? Perhaps I should I just learn to read and shut up, but I would protest that Rodenburg meant something else.

Luckily, both of these problems are obliterated by a third one: The total amount of training, measured in distance, that this unknown number of people undertook wasn’t enough to draw meaningful conclusions. (I’m tabling the additional confounding issue of being forced to assume that the average quality of the training miles was invariant between all groups analyzed.)

When looking at the y-axes of these graphs, bear in mind that the numbers represent 16-week mileage totals.

So, in 2022, the men and women in these datasets aiming for sub-four-hour marathons averaged about 24 and 21 miles a week in training for a hilly 26.2-mile race. In 2023, these figures dropped to about 20 and 18 miles per week. Meanwhile, the 2023 group with a more modest collective aim—the murky “4 Hour Finish Goal”—trained slightly less immodestly this year, with the women in this category hammering out a shade over 24 miles a week and the men around 20.

You’re not going to get a whole lot of useful information about the effects of marathon training from people who don’t actually train for marathons. In the same spirit, you could have give one three-year-old member of an identical twin pair one hour to study differential equations and the other twin two hours of prep, then have both of them take a standard AP Calculus test; it should be plain why trying to figure out whether the extra studying made any difference for the second sib would be a waste of time.

After presenting these graphs, Rodenburg observes that “After years of stagnation post-pandemic, more women are racing marathons in 2023, with an 18 percent increase from 2022.” Has it really been that many years since “the pandemic”?

Rodenburg also describes “the wall” as “a point in the race where you run out of energy.” I’m trying to imagine what it would look like for a human body to suddenly become completely devoid of energy in a formal sense, while taking part in a marathon or otherwise.

This could mean the potential energy stored in the chemical bonds between the atoms in the molecules of the body’s 38 trillion cells (give or take) vanishing all at once, or it could be the flash-decomposition of every molecule of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) that powers our biochemical processes. It could even mean an effect akin to that produced by running through a large, dense cloud of hydrogen cyanide gas, which would rapidly result in the systemic cessation of respiration at the mitochondrial level and the convincing appearance of a total loss of energy while in fact leaving that energy intact but terminally unavailable for locomotion.

After explaining that the data show that women are generally better at pacing themselves in marathons, Rodenburg then moves on to how successful women were at reaching their goals versus men.

Strava said women were more likely to hit their goal in all pace groups. For runners targeting a finish under three hours, women were 33 percent more likely to meet their goal and 12 percent more likely to meet their goal under four hours.

The bit seems relevant, and seems to contain the findings that chiefly underwrite the story’s manbun-tugging headline. But readers are denied yet another critical piece of information: How successful were these runners at reaching their goals in absolute terms? That is, what percentage of men and women in each time group achieved their goals? The story doesn’t say, although Rodenburg does helpfully note that “plenty of runners don’t finish in their race time.” (Actually, every runner who completes a race finishes “in their race time,” by definition, even if some of them miss their goals.)

Given that none of these groups boasted meaningful training volumes, it seems fair to assume that only a low percentage of the runners in each group attained their time goals. If so, this would make the cited differences less impressive.

For example, if 9 percent of the male runners “targeting a finish under three hours” (and where did this group come from?) achieved this while 12 percent of the women did, there’s the 33-percent difference Rodenburg cites. And if 28 percent of the women looking for “their goal under four hours” achieved this time while 25 percent of the men did, that’s a 12-percent inter-group difference.

Pharma companies and their Centers for Disease Control, Food and Drug Administration, and mainstream-media lackeys—the remaining few “journalists” who can so much as sum one-digit numbers in their heads, that is—play these percentage-stacking games all the time in their efforts to conceal, or obfuscate the meaning of, the absolute values of metrics when looking at differences between groups. I don’t think this was Rodenburg’s play here; I suspect she was typing the same words into this article that she was reading from something supplied by some clever-enough Strava grunt.

Rodenburg at least provides a numerical measure of how badly the people who missed their goals flopped:

[E]ven when missing their goal, women fared slightly better than men, finishing an average 8.2 percent slower than their goal time compared to 8.7 percent for men.

Missing a goal of four hours by 8.2 percent means running close to 4:19:41, and missing it by 8.7 percent means running in the range of 4:20:53. The story here—if there even is one, given the lack of information about the total number of runners analyzed—isn’t the trivial difference between how badly each group fell short, but the fact that 20 or so minutes is a lot of unwanted time no matter a marathon runner’s goal, around 45 seconds per mile.

Rodenburg is a frequent traveler in the exotic lands where rapid-fire electronic running content suitable for today’s shart-flecked brains is produced. Perhaps she struggles less to support her thesis when the subject not only doesn’t require any kind of analysis but defies all possibility of such a thing.