Some of the top finishers at the 2022 Mt. Washington Road Race have some weird results profiles

The race being half the usual distance concealed what was twice the normal "WTF" factor

For some readers, this will only augment the cries of “misogyny” and “incel” in the comments below this post. For others—and maybe for some readers in the first, already mistrustful group—it might help explain why I went to town as hard as I did on Ashley Paulson. I was going to include what’s here in that post, but I’m glad now that I didn’t, even if it would have shed additional light on why I’m so suspicious of certain athletes. That post turned out messy enough.

People who, for lack of a clearer characterization, distrust these posts seem more skeptical of their salty language and profane sidebars than even their material fuckups, the post about Paulson containing one such mistake. I noted this mistake in an edit, and though my erroneous belief about an information-transfer timeline didn’t influence my conclusions, it was still a fuckup. This bothered me more than it seemed to bother anyone else.

Anyway, the most recent edition of the Mount Washington Road Race, which started in the 1930s and became an annual event during the Lyndon Johnson presidency, was held on June 18. This is usually a 7.6-mile climb from the start at Pinkham Notch, N.H. (elevation 1,638’) to the mountain’s 6,288’ summit. There are no downhills, not even little dips. The only flat part of the race is the first hundred yards or so, and after that, running up the Mount Washington Auto Road is like being on a treadmill with the grade set at 11.5 percent.

Well, that’s not quite right. “A treadmill in the bed of a speeding truck” is closer, at least in some years. The geographic feature known as Agiocochook (“Home of the Great Spirit”) by the Abenaki people and named Mount Washington by European settlers is best known for its ferocious winds (its lifetime PR stands at 231 MPH), its views reaching over a hundred miles west into the Adirondacks and east as far as the Atlantic Ocean, and the once-impressive mortality rate of its visitors from Massachusetts.

Conditions so far have never been lethally bad for the road race. But this year, for the second time in race history, bad weather forced the organizers to drop the finish line to the usual halfway point at 3.8 miles (the same thing happened in 2002).

“The Mountain”—if you’re a local and you say that, people know you mean the one with a prominence exceeding that of every mountain peak in Colorado except for the state’s highest, Mount Elbert—is situated amid a uniquely macabre confluence of weather systems. If you’re from Colorado, you may laugh at the idea of 6,288 being considered much of a peak, but if you have ever hiked the trail to the top of the mountain on the wrong or even a typical spring afternoon, you’ve had the experience of striding along in a t-shirt in a clear, 70-degree day to start and finding yourself being pelted with marbles of hail and blown around by 50-mile-and-hour winds at the summit. Whereas it makes sense in most distance races to shed layers as you go, here, in some years you would almost be better off adding a windbreaker, or at least some of those really stupid-looking arm warmers the in-crowd is so aswoon over, along the way.

The race was the home of great spirits both provisional and rapacious this year. For the second time in the race’s nine-hundred-year history, the weather forced organizers to place the finish line at the usual halfway point. But this didn’t stop two women from producing startling performances, one especially so (results). 38-year-old Kim Dobson of Eagle, Colorado was the first woman in 31:56 (net time), while 40-year-old Amber Ferreira of Concord, N.H. was second in 34:29.

Some basic algebra is required to highlight what happens when the Mount Washington course is cut in half.

Ordinarily, over the full 7.6-mile distance, a strong climber will be able to approach or even exceed his idealized 20K time, whereas weaker climbers and slower people generally find their “Mountain” times approximating their half-marathon times. Looking at the 2002 results as a partial guide, and using the fact that the climb to the summit is almost uniform, translating a 2002 or 2022 3.8-mile time to an equivalent performance over the whole 7.6-mile road means multiplying by about 2.1. This is the same multiplication factor commonly used to get a flat 20K time from a 10K time.)

Using this logic, a top Mount Washington finisher’s 3.8-mile time should be in line with a flat road or track 10K time, maybe a little faster. I confirmed this reasoning with Dave Dunham, who knows more about this race than anyone alive, and on top of that is an insufferable math and numbers geek.

I also did some light data-sampling. This year, Joe Gray, (enter Wikipedia voice) widely considered the most accomplished American mountain runner of all time (exit voice), easily won in 27:43. Gray’s track PR is 28:18 from 2017, but he seems capable of matching or approaching that now. Runner-up Everett Hackett, who ran 28:50 up the auto road, ran 29:36 last year on the track.

But most of the top men probably couldn’t run a 10K within a minute of the time they took to ascend roughly half of New Hampshire’s most noteworthy hill in June. for example, Eric Blake, who ran 29:11 at 43 this year, is an absolute animal on verts, but I doubt he could break 30:30 on the track anymore. And to be fair, the weather is usually shittier for the second half of the race even if the road itself changes little (except for that headwall at the very end, oh my). So, it might be better to lean conservative and multiply this year’s times by 2.15 to get a full-ride estimate. That would yield a 59:36 for Gray, who ran 58:15 in 2015, and who would surely prefer I stick with the 2.1 factor (yielding a 58:12).

I hinted at my interest in this year’s event shortly after the race by sneaking the information below into an images-only post.

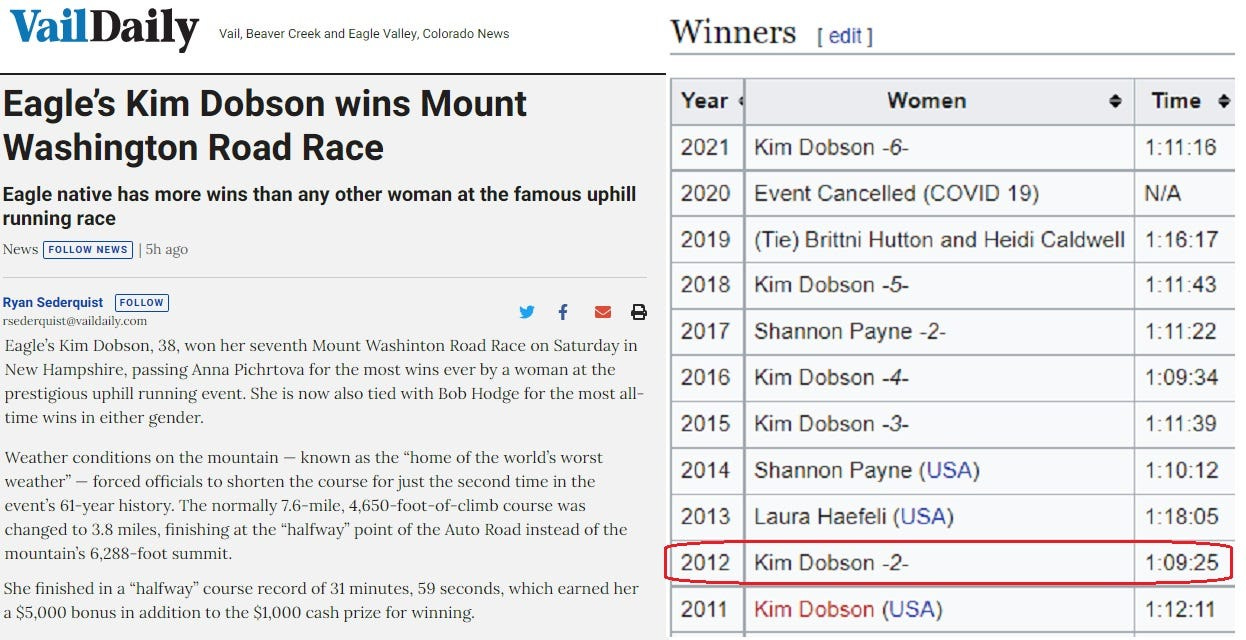

Dobson has now won the race seven times, with a personal best of 1:09:25 from 2012. Her 31:56 from this year, using the 2.15 multiplication factor, projects to around 1:08:40 for the “whole” race. Since Dobson has run 1:09:25 and 1:09:34 previously—albeit ten and six years ago respectively—this isn’t that much of an outlier-in-disguise.

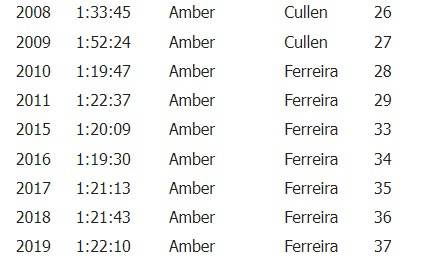

Dobson has also won the Pikes Peak Ascent, basically a half-marathon for people who hate oxygen, six times. In 2012, a couple of months after her 1:09:25 event PR at Mount Washington, she annihilated the PPA women’s course record with a 2:24:58, placing her sixth overall.

Coincidentally or otherwise, the next year, the Pikes Peakers instituted doping controls—after a fashion, as Bilbo Baggins would put it.

Someone as flat-out fit as Dobson should be able to run sub-16:00/sub-33:00 for 5K and 10K even if she has no interest in flat races, a curiously prevalent trait among the oxygen-averse. But her Athlinks shows almost no historical activity for Dobson in “ordinary” races, where she could easily pick up at least some occasional grocery money.

Meanwhile. Ferreira’s 2022 time of 34:29 projects out to around a 1:14 for the usual race distance.

These are her historical results from the race.

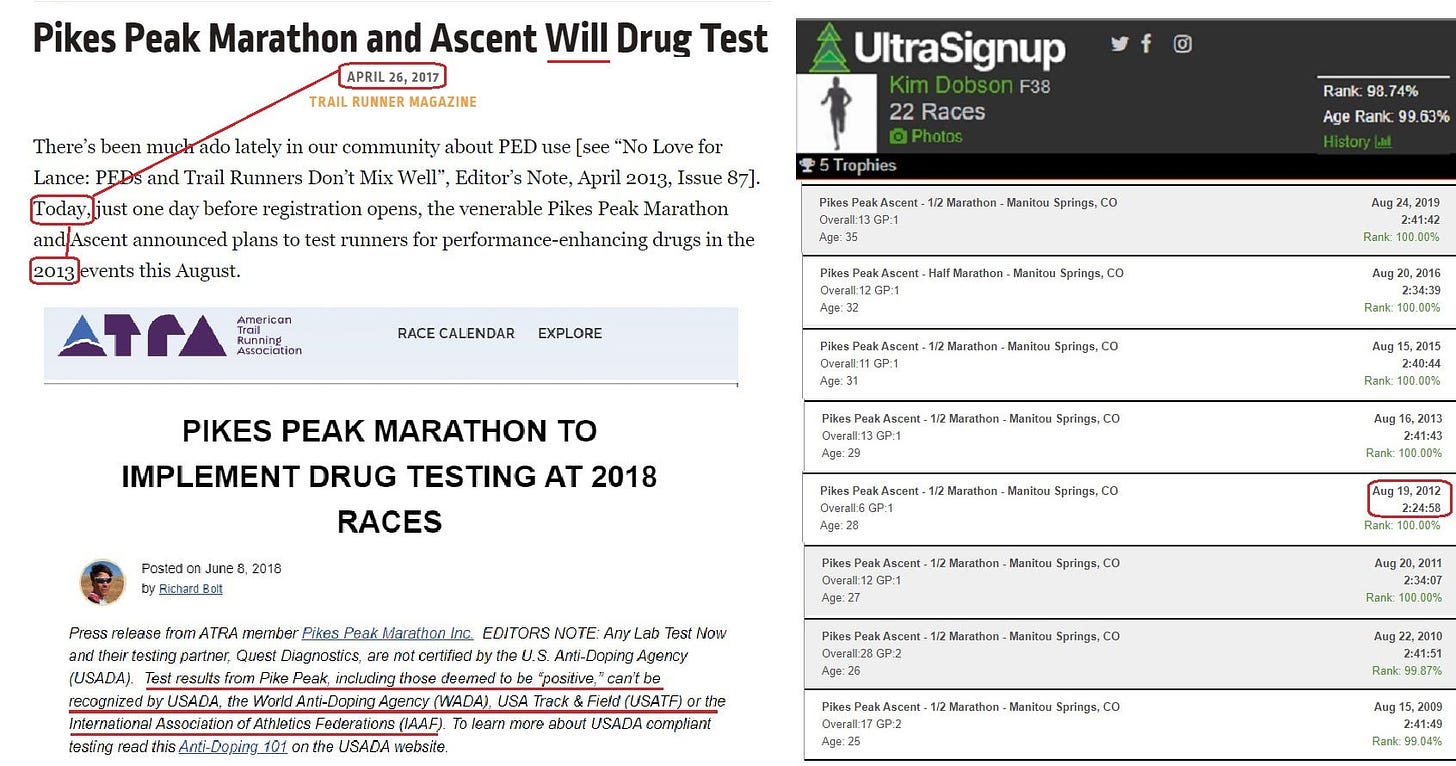

Ferreira is not new to competitive running. According to her Athlinks profile, she is a 9:07:36 Iron(person) triathlete who has been competing at a high level since graduating from college, winning a couple of national snowshoe titles along the way (that 2011 article omitted the 2014 win). And unlike Dobson, Ferreira has run a lot of “normal” road races. In April 2019, she ran 18:20 on a flat 5K course, worth about 38:30 for 10K and 1:20:50 for 20K. Two months later, she ran 1:22:10 at Mount Washington, right in line with what the April 5K suggested. She also seemed to be slowing down slightly throughout her thirties, a practice most athletes favor.

Last August, Cullen gave birth to a baby boy. Ten months later, she went out and performed far, far in excess of her previously demonstrated capabilities. No matter how you look at that 34:29—as a 1:14 for the shole shebang, as a ~35:00 10K, or as at worst a half-marathon in 1:17-1:18—this was an absolutely phenomenal result.

So what is it? Is the “baby bump” worth close to a 10-percent fitness gain even at a time when athletes are inexorably starting to slow down? Did Ferreira find a way to streamline her postpartum training for supra-optimal results? Or could this be a less-appetizing case of someone whose entire life as an athlete, a coach, and now a mother is sufficiently intertwined with her self-identity to precipitate previously off-limits choices—especially with the vagaries of COVID-19 and newer racing shoes helping offset any suspicions in this area?

Paulson, Ferreira, and others I could rake over the online coals in a horrible mixed metaphor of a dragging fit a general profile of the sort of person who responds to an incipient or expected physical decline by making up the difference in ostensibly verboten ways. I’ve met people like that out here, too, only they’re worse because they never had a reputation to protect in the first place.

A few years ago, during a jog, I ran into some guy of around fifty who was hammered out of his mind on a bike (well, it was stopped at the time) and who wound up bragging about his testosterone-patch supply and all the other shit he was on, just so her could hang on group rides and maybe bang out a sub-20:00 5K. This is in part yet another “Boulder thing,” but my theory is that a lot of these guys are responding to a sexual shut-off or a long-overdue affair by the missus and are responding in ways that both bolster their egos and shrink their suddenly useless junk.

I know I’ll catch heat for this one, and it doesn’t help that Ferriera lives in the town I grew up in and knows a few of the same people. I’ve met her in passing, at a group run in Concord some years back, and she was nothing but pleasant.

None of which explains how someone suddenly goes, in effect, from being a consistent 1:19-to-1:22 performer as a highly trained endurance athlete to being a 1:14-like performer at the same venue, with the most significant event in between in the athlete’s life being giving birth. There is simply no way to fog up the starkness of the fitness contrast with nonsense. If it’s not doping, it’s something new.

Even if people don’t agree with my reasoning in posts like these that include unkind judgments that can’t be formally settled, I think it should be evident that I’m not moved to do this so that I can take serial shots at women, fat people, ethnic or other minorities, or the unabashedly and unavoidably moronic. I’m tired of seeing lying, cheating, and grifting, all of it pervading the media and all of it increasingly sanctioned from within.

And it’s coming from so many different angles that by now I have “targeted” multiple extraordinarily white men (David Roche, Martin Fritz Huber), one man who until this moment I considered white but is most likely of Latino descent (Chris Chavez), among the whitest women ever from Iowa (Shelby Houlihan) along with her virtually all-white teammates, multiple very thin black men and women (depending on how you treat accusing Ethiopians of doping), one notoriously boisterous obese black woman who most likely did not grow up wealthy (Latoya Snell), more than one flamboyantly narcissistic white woman at The New York Times who certainly did (Lindsay Crouse among them), and a tabloid-trash-style editor of apparently Persian heritage (Molly Mirhashem), along with (singly or as a group) Christians, Democrats, Republicans, Anthony Fauci, the CDC, the NIH, the Biden administration, Donald Trump, the Clintons, the CIA, every news channel there is (those are the same thing), and jaundiced bloggers with far too much spare time. There may be others, but I’ve spared the Jews and the Jehovah’s Witnesses for now because these sects have recently conspired to bring down my whole operation.

There is a common thread here, and it’s obvious what its strands are not woven from.

Also, the idea that I do this for clicks, money, or glory is self-evidently insane. None of this is making me look like a cool person. It’s not going to land me a lucrative hero’s welcome on a soon-to-be-invented anti-Woke streaming-service for booger-munching dipshits. I’ve permanently severed some once-meaningful ties not because I enjoy making enemies but because when I’m given a choice between the evidence and in-group popularity, it’s not a choice. The result is what it is.