The best of the NCAA has been an expanding club for years, despite losses to the pro ranks

Superspikes are making an undeniable impact on college performance lists, but things were hardly stagnant before the 2021 indoor season

One way to look at global warming—besides either denying the phenomenon wholesale (a false, now passé idea) or trumpeting that it will soon blister Earth into non-habitability (a false, now trendy idea), is this: The assortment of phenomena resulting in rising average temperatures worldwide over the past few decades likely represent a superimposition of anthropogenic effects on natural effects. That is, perhaps the Earth’s climate is, at baseline, undergoing a obviously non-modifiable warming trend as part of a relentless cycle-within-a-cycle, and meanwhile, the warming effects of human-produced skyguck have been additive. It would not be the first time in human knowledge-gathering history that a single causative factor failed to be responsible for an observed trend, however politically and intellectually expedient mutually exclusive assertions and theories have become.

Similarly, “superspikes” have clearly had such a revolutionary, and numerically revisionary, impact on elite track running since their release about fifteen months ago that it is tempting to ignore the fact that, collectively, those striving toward or already enjoying world-class status had been upping their game for years as it was.

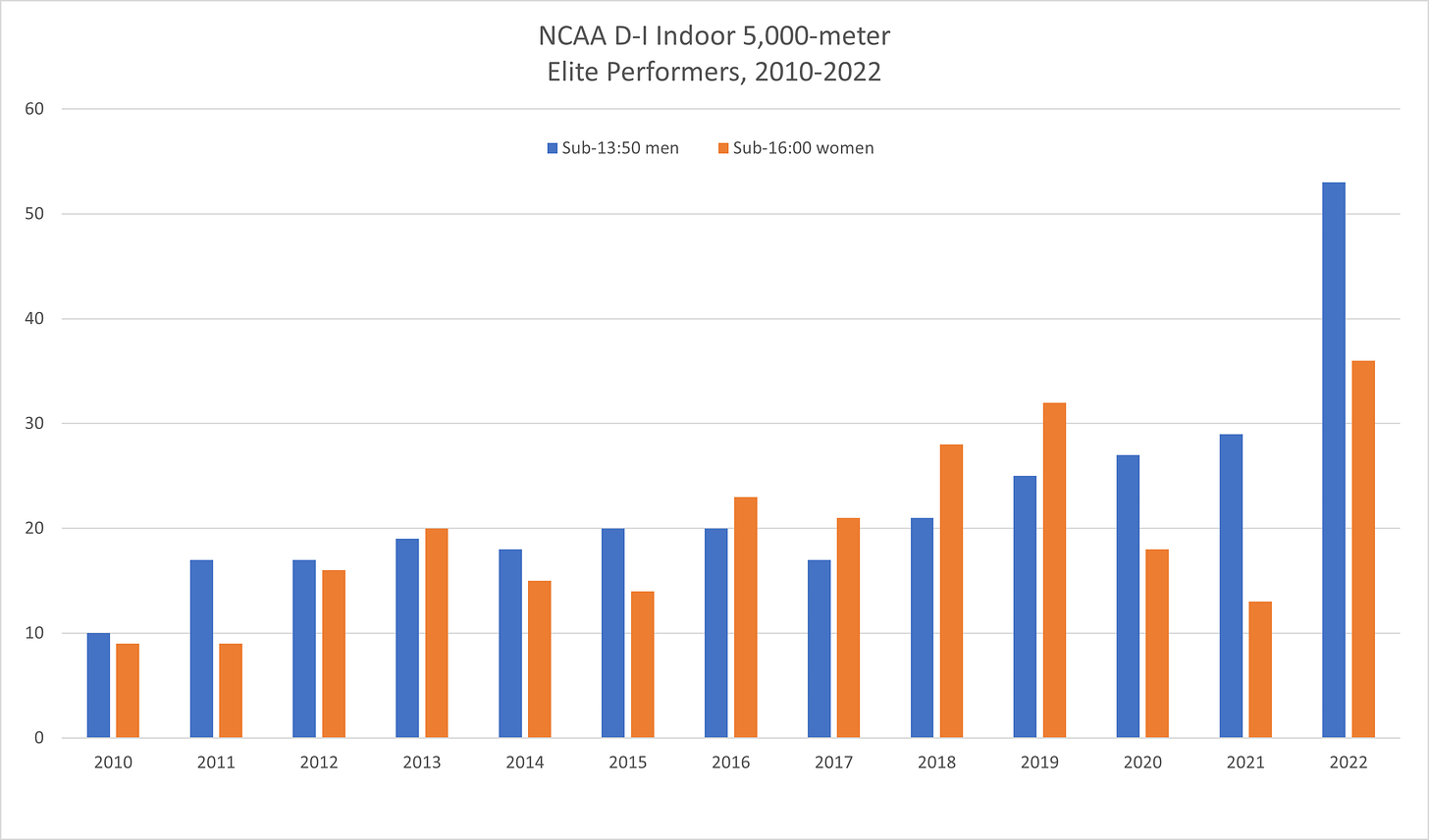

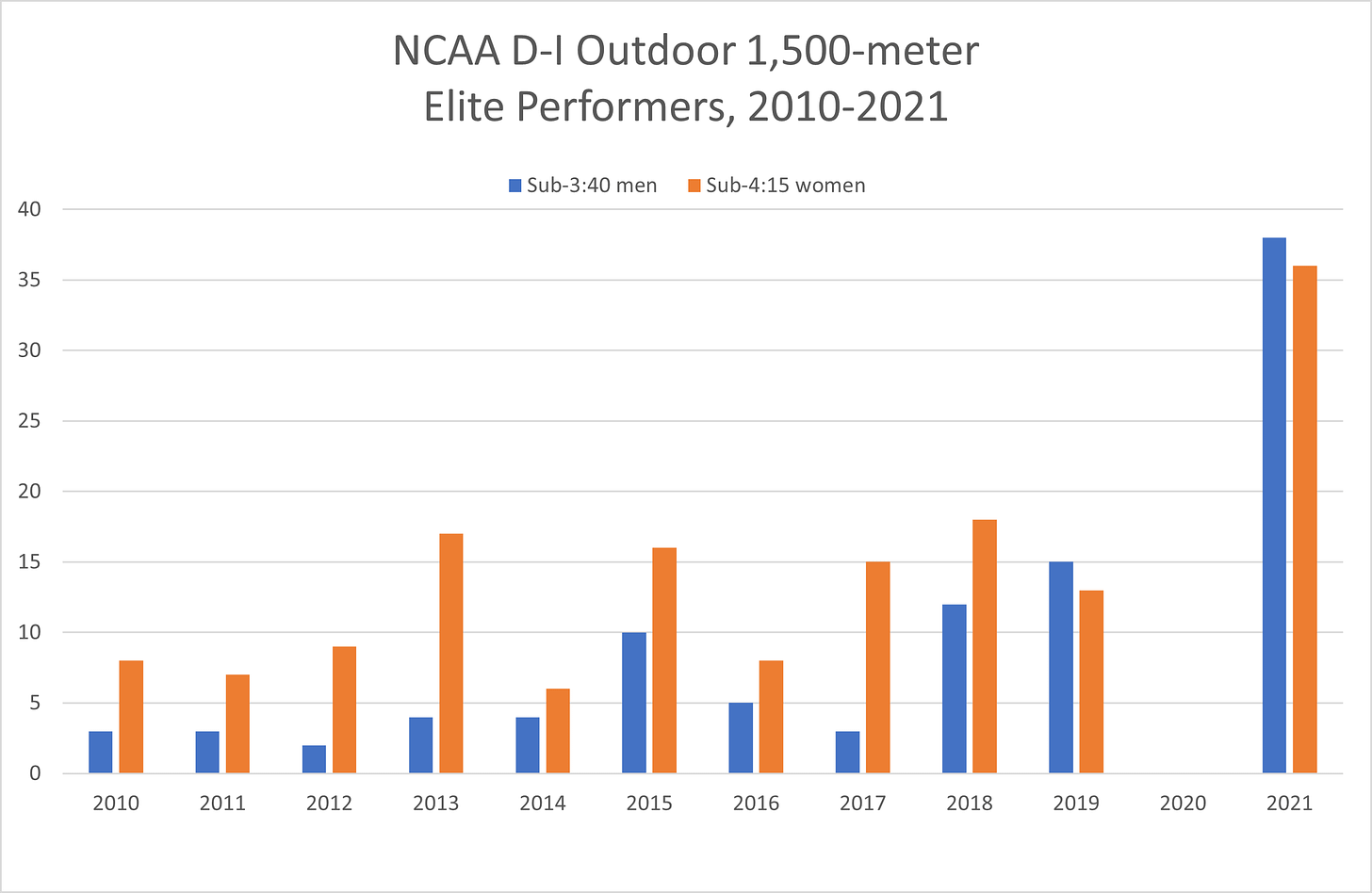

Because of the ease of researching U.S. collegiate performance lists as far back as the spring of 2010 using TFRRS, I decided to see how the best runners in the NCAA have been performing over the past decade-plus. To do this, I created two data sets: One including the number of sub-13:50 Division I men and sub-16:00 Division I women in the 5,000 meters in the indoor seasons from 2011 to 2022, and the other including the number of D-1 sub-3:40 men and D-1 sub-4:15 women in the 1,500 meters in the outdoor seasons from 2010 to 2021.

Those aren’t perfect pairings; sub-13:50 is worth a few more World Athletics points for men than 16:00 is for women, and a 3:40 is worth closer to a 4:12.5. But using perfectly even standards per the WA tables would have left me with too little data on the women’s side, especially in the earlier years. Also, the cut-off times I used for the 1,500 meters were meant to be a notch closer to world-class than those I picked for the 5,000 meters.

Notes on the graphs below:

U.S. collegiate running has now been completely free of Covid-driven restrictions and hacks for almost three straight competitive seasons: The 2021 outdoor track season, the 2021 cross-country season, and the 2022 indoor track season.

The 2020 NCAA indoor track season produced useful data despite the cancellation of the championship season in early March, because in most years, every collegiate runner records his or her fastest time of the season by late February. For the same reason, I also included this season’s indoor data.

The 2020 outdoor season was completely wiped out, while a reduced 2020 cross-country season led the NCAA to split the winter of 2021 into indoor track and a cross-country championship season.

In summary, then, the data for the 5,000 meters is nearly complete for 2020 and 2022 and incomplete to an indeterminate extent for 2021. The data for the 1,500 meters, on the other hand, “merely” skips a year.

Finally, Nike released its revolutionary Dragonfly ZoomX racing shoe—not pertinent to cross-country—in the late fall of 2020.

It is clear from these graphs that the number of very good NCAA 5,000-meter runners was trending steadily upward for both sexes before superspikes came along, and that the same uptick appeared to be in play at the level of exceptionally good 1,500-meter runners. It is also plain as can be that superspikes have led to a far faster accumulation of dust on older performance lists than ever would have happened otherwise.

It’s worth pointing out that the number of runners who leave collegiate running early for the pros or skip it altogether in favor of a contract has, I think, been increasing throughout this time. The total number may not be high, but had they all run in college and expended their eligibility there, these graphs would look different, and the baseline improvement in collegiate running—that is, the element divorced from superspikes—that’s been underway for at least a decade would appear even more pronounced. In a way, though, this “problem” is self-sustaining: The closer to world-class a collegiate (or high-school) runner is, the more likely he or she is to have the professional option available. That is, young runners are, in an increasing number of cases, becoming too good for the college scene.

I have to emphasize the imperfection of these graphs. As noted, I didn’t choose perfectly matched standards, and even had I done so, I would have chosen somewhat arbitrary cut-off points. But I think this sampling is sufficient to establish the general idea: Credit college running for independently driving the best of the best closer to the top domestic level of the sport, whatever the mechanism. As for the main drivers of that mechanism, I’ll toss out there two ideas that are mostly just guesses: A slight increase in the number of exceptional foreigners joining the NCAA, and a better and better crop of young Americans—kids who have been getting solid guidance since being identified as talents well before their high-school years. The age of the college standout who did zero formal running in middle school is, I believe, waning fast.