The Bolder Boulder should either revive or scrap what's become of its professional race

"Teams" of two and field sizes of fourteen aren't enough to keep a stand-alone road 10K afloat, as coasting on the merits of a musty reputation is never an endless ride

The Bolder Boulder, a recently reinstated Memorial Day tradition, is either the largest or the second-largest 10K road race in the United States. Most Boulder-area folx, including reporters, seem to believe that it’s the biggest, apparently as an article of faith; everywhere else, it trailed the Peachtree Road Race by around 17,000 entrants in 2019.

This made the July 4 jamboree in Atlanta about 40 percent larger in history’s final pre-covid-impacted year. In fact, the Peachtree 10K has been larger than the Bolder Boulder for a long time, with the size-gap between them slowly increasing.

Bigger may not be better for all involved outside the finance, sex, and firearms worlds, but if you’re going to serve up verifiable superlatives, it’s good practice to situate your claims in the same ballpark or at least the same league as reality.

In 2019, the Bolder Boulder had 42,587 official finishers, down from 45,682 in 2018 but consistent—unless you’re the race’s accounting team—with the 44,660 who finished the race in 2017 and the 44,677 who wobbled all the way to Folsom Field in 2016.

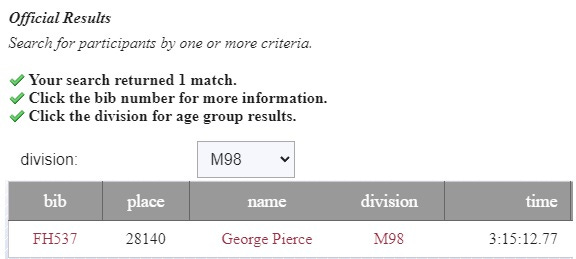

Thanks to something in the air that no one can quite put their finger on, the 2020 and 2021 editions of the Bolder Boulder were canceled. It was revived this year, and although the results don’t seem to offer an uncomplicated way to determine the total number of finishers, I’m guessing it wasn’t significantly larger than 28,140.

George Pierce already being 55 years old when the first Bolder Boulder was held in 1979 (when Jimmy Carter was the U.S. President) and finishing the race this year (when Jimmy Carter was only 97) is enough to provoke temporary vertigo.

I would have expected a much stronger rebound in numbers this year considering how many people who live around here do little besides run or at least talk about running. Then again, a huge fraction of the annual field treats the Bolder Boulder and any road race its size as a slowly roving block party, and it’s hard to say at this point if the drop-off in 2022 numbers is mostly the result of this faction sitting it out—inflation, after all, does affect some people in this set of zip codes—with the number of actual runners, including “serious” ones, more or less stable. I also suspect that Boulder and the Denver metro area generally includes a disproportionate number of people who still fear catching covid from large gatherings, based on both behavior and the area’s mostly blue electorate.

But the Bolder Boulder isn’t the only big U.S. road race that didn’t come close to its former field size in the first year of nominal normalcy. The Broad Street Run, a 10—miler in Philadelphia, attracted 20,478 finishers this May, down from over 35.000 in 2019. The Peachtree 10K had about 35,000 entrants.

Using these three large races as metrics, it appears that about three in every seven participants in these longstanding traditions opted out this year. This is another consequence that easily could have been avoided had the world’s response to the coronavirus been remotely proportional, but it’s not the fault of anyone reading this that this wasn’t the case. Authoritarians far above the pay grades of even the most affluent Beck of the Pack readers ensured that this would happen, and the same people are currently working on achieving an even greater level of strangulation of everyday citizen happiness.

Apart from anything related to the pandemic, the Bolder Boulder’s professional men’s and women’s races, which have been sliding toward irrelevance for years despite frequent formatting tweaks, are not worth keeping as stand-alone events.

The citizen’s A-wave of the Bolder Boulder, which I ran in 2017 (I’m the uglier person in the photo below) and 2018, starts at around 7 a.m. Entry into this wave requires running under 38:00 or the equivalent at another distance. The AA-wave is next, either 45 seconds or a minute later. I have no idea when the ZZX-wave or whatever is last gets moving, but the result is runners and walkers still approaching the finish line in a steady stream when the pro races begin, with the women’s at around 11:10 and then men’s at around 11:20, right when it’s usually getting nice and hot.

Because the race finishes in a football stadium, the idea of having the pro race last seems to be ensuring that hundreds of spectators will be within or close to the confines of Folsom Field when the pros start to cross the finish line. In reality, most of those people are not spectators, they’re tired runners who are simply trying to leave the area and find their cars and are not remotely interested in who wins anything.

Nell Rojas passed me a few times while doing strides on the Boulder Creek Path this year before the start of the pro race, dodging me and others with dogs as well as runner’s who had just finished and left Folsom Field, and realized that this precarious option was better than trying to dodge people still in the race and occupying most of Folsom Street.

The format of the pro race has changed over the years. It’s been promoted as an international team race for as long as I can remember, but the teams used to consist of three people and there used to be a dozen or more teams in each race. This year, there were only 16 finishers in the pro women’s race and only 14 in the pro men’s event, with Americans Aliphine Tuliamuk (32:58) and Leonard Korir (29:28) leading the way. Tuliamuk ran a sparkling time; the last time an American ran close to 33:00 at this event was in 2014, when Shalane Flanagan’s 33:05 placed her second to Mamitu Daska’s 32:21. That was before they moved the starting line of the pro race from 30th and Walnut to Taft and Folsom, close to the stadium and the finish. Flanagan had run 2:22:02 at the Boston Marathon five weeks earlier.

(Finding the results of the pro race on the Bolder Boulder website has always been close to impossible. The race prides itself on “accuracy and advanced race-day results,” which it shouldn’t, because on July 10, six weeks after Memorial Day, the International Team Challenge page hasn’t been updated in three years, and the link to the 2022 "A”-wave results on the main results page links to the 2019 results.)

Who really wants to run a road 10K with the near-assurance of spending most of it alone, under a warming sun, on a course already promising a time redolent of the rarely run 10.5K distance?

Getting into the A-wave is clearly not an elite accomplishment, although someone who qualifies with a 37:55 on a flat local course has run the equivalent of a sub-36:40 at sea level (the difference is about 3.6 percent at ~5.300’). The course itself adds about 2 to 2.5 percent compared to an airport-runway-style course or track. So, if you actually break 38:00 at the Bolder Boulder itself, you’ve probably run the equivalent of a sub-36:00 in Palo Alto. Better than it looks, but still far from “fast.”

But up front, the A-wave is fast. It’s usually won in around 30:30 to 31:00 for men and around 34:15 to 34:45 for women. Nailing the faster ends of those time ranges is good for close to 29:00 and 32:30 at sea level, all for no prize money. This year, Laura Thweatt, who ran 32:01 on the track and 1:12:39 for a half-marathon in March, won the women’s division of the event in 34:59, five seconds ahead of suddenly resurgent multi-mom Neely Gracey. Yep, the course really is that nasty, and none of it even looks that nasty until around 5.9 miles in. It’s just a grind, with few places to coast and gather yourself—which, if you do, a parade of people will pass you even if you’re moving at close to 6:00 pace.

Americans Sara Vaughn (35:14) and Rojas (35:35) ran slower times in the pro race than the top women in the citizens’ race did. This was under harder conditions, but the same overlap between the elite women who got into the elite race and the elite women forced into the early-bird fun-run occurs every year, and it happens on the men’s side to a lesser extent.

The Bolder Boulder should start its pro race along with the A-wave at 7:00, so that the whole event is a continuous race. If, as the runners are lining up, the organizers want to separate the true pros from the rabble—”true pros” being runners specifically invited to the event, along with applicants whose demonstrated bests are below established cut-off times—they could use a rope, like they used to do at the Boston Marathon to separate sub-elites from the first corral until moments before the start. Or they could just eliminate the international competition and stop inviting runners, and just put that cash into an enlarged prize-money purse available to all entrants.

The idea that people who want to watch world-class runners participate won’t turn out if they have to be at Folsom Field by 7:30 in the morning is dumb. People like me would be more inclined to head for the finish to watch the elites if we knew that the finish area wasn’t yet going to be awash in hobbyjoggers (a few dozen of them doing bong hits) and their waiting family members (several of them boasting Jen Psaki costumes). The weather would (usually) be better.

The only reason to not make this change—and I think that back in the 1980s, the elite race was much like what I have proposed here—is to have more people continue to be incidentally present for the pro race. Well, not “only”; the current scheme does allow those involved in the production and execution of the professional race (e.g., the video team) to sleep off their holiday-weekend hangovers for a couple more hours if necessary, a nontrivial benefit given the alarming prevalence of runner-besottedness ‘round here.

As for the Bolder Boulder as a unit, I don’t think the people who run the thing care nearly as much as they pretend to about its quality, especially the event’s professional arm (more of a digit or excrescence these days). The same company that owns the Bolder Boulder started a similar Labor Day race in Fort Collins in 2017, the FORTitude 10K. The company sent an e-mail on June 10 stating that the race has been permanently discontinued. The owner is in this for the money because why not, and if the company’s flagship event continues to flag numbers-wise next year, he’ll probably sell it to, say, Jeff Bezos, who will quickly move the event into a low-altitude Amazon fulfillment center. Or Robin Thurston, who will then lose it in the crypto market. And no one will care, because the citizenry of Boulder, until someone finally torches the whole self-fellating eyesore, is continuing to slant further toward rich people who dislike road races as a rule and force all of them but the Bolder Boulder into industrial parks and onto dedicated bike paths.

Whenever I read one of my own posts in its entirety, my first thought is always a version of, “I really should have chosen a different hobby.” No one, I’m convinced, can actually read any of this banal output by me or anyone—garbage about distance running—and find it interesting. I think most older “running fans” are simply too lazy to prune their Internet bookmarks from 2005. I only keep an eye on “the sport” because most of my friends and almost all the random ding-a-lings I’ve become aware of in recent years are involved in it somehow; my interest is thus understandable, but habit is still a feeble excuse for not disengaging from a dilapidated social freak-show. I hate virtually all of you with a thrumming and throbbing (but non-sexual) passion so intense it makes my nails grow longer by the week and foul brown things topple out of my rear end just about daily.

I could be writing about literal penis-mites, or the tall, loud organisms indigenous to Colorado that feed exclusively on scrotal cheese gathered from marathon port-a-johns, and be producing (in my mind) far more compelling material than I do. Writing about social and cultural traditions means writing about human beings, the sight of which now makes most normal people like me want to run the other way.