The elite women's field at the 2023 Boston Marathon, like the event itself, is officially insane

A smart-running American woman might place as high as fourth in a formidable and proven, yet mostly "untested," field

I was originally tempted to overload this post with gripes about the Boston Marathon’s progressive dilution, and about its bloated four-day expo being populated by self-dealing goobers with transparently dishonest, unqualified, and even menacing presences. But I decided that I can suspend most of these thematic bemusements for at least few days.

For one thing, that’s all these expos have ever been—attempts by people associated with running to push what they’re selling. There’s no harm in peddling whatever wares or concepts you have to consumers in the leisure class. The larger the Boston Marathon field grows as a result of basic, immutable economic pressures, the more expansive its expo accordingly becomes.

For another, while sham social-justice efforts have made many if not most companies and media figures (social and traditional) insufferable, thereby amplifying the number of non-running fringe characters associated with the production of the 2023 Boston Marathon show, I’m not sure how much worse this is in running than anywhere else. My perception that it might be is influenced by my unjustified idea that running should be more resistant to stupidity than other subcultures, which is nothing more than feeble wish-making.

To devote hundreds or thousands of words to the usual suspects would be to ignore legitimately delicious drama. Up front, there are still men’s and women’s races of unprecedented intrigue to look forward to. (From this point on, assume I’ve already conceded that whatever heroics I highlight are almost certainly powered by ostensibly illegitimate forces, no different from any other high-stakes footrace or other athletic or non-athletic competition.)

I’ve already mentioned that world-record holder Eliud Kipchoge is running this year.

I also promised a preview of what should be a historically fast women’s race. As I have done in the past, I’m going to defer to Letsrun’s undertaking of this task. (The Abe Simpson reference makes me wonder if John Kellogg had a hand in this.)

I’m not merely being lazy; I just can’t think of anything I would have come up with that’s not in the LRC article, other than to account for one factor the piece did not (and, being published on Friday, could not): the weather. If the headwind and rain are significant enough to discourage course-record chases—and considering the putative margin Kipchoge and multiple women have on the respective marks they’ll chasing, it might have to be worse than breezy or rainy to force “tactical” races—then the field will treat the race like any other Boston Marathon, and jostle around waiting for someone to make a move.

Sort of. Kipchoge will almost certainly be allowed to dictate the men’s race, and there is really no predicting what he’ll do; he may produce eerily reliable outcomes, but such is the oomph of his dominance that he’s taken startlingly different paths to get there. It’s almost terrifying that he went out in 59:50 for the first half last fall in Berlin and still ran 2:01:09. That means he could probably have run 2:00:30 had he gone out around 25 seconds slower. If he’s retained that level of fitness, he can run under 2:03:00 in Boston—which he wants to do—in relatively crappy conditions.

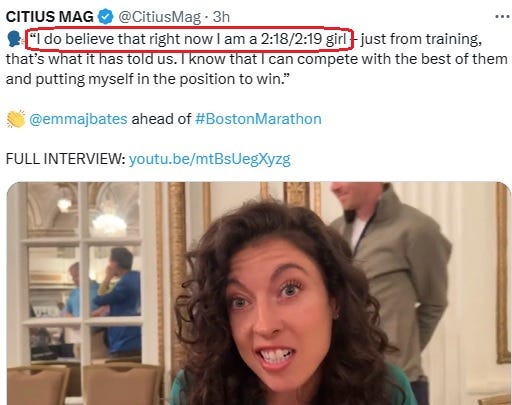

American Emma Bates (2:23:18 PR from the World Championships last summer) also has high ambitions. If she says she thinks she can run 2:18-2:19, then I have no doubt she plans to go out in 1:09-flat. I don’t know how the weather will affect that, but Bates is my pick for the top American woman as long as she makes somewhat appropriate concessions to the conditions. I can see her placing between fourth and sixth as many of the Africans drop out or fade after overzealous starts, but not if she goes out with them.

It would be unfair to say that the Boston Marathon has lost its luster until its competitive fields go into serious decline, which clearly hasn’t happened. The sport only makes me wince when I peer too closely at some of its warped, fattened-up and dumbed-down facets and the widespread pretense that obvious bozos, liars, and social arsonists are disseminating helpful messages.

Rather than comment on this one, I’ll instead refer to what it reminds me of:

I’m also going to suggest, not for the first time, that either distance running doesn’t suffer from an intrinsic racism problem—at least not against “nonwhites”—or the sport needs better oppression-researchers. The latest evidence:

If Alison Desir were not a coward who blocks people who offend her with legitimate questions, I’d ask her what her proposed solution to this “problem” is. Would she be okay with a 51% “nonwhite” majority in the entire region, or does each of these towns need to get there independently? And, while I don’t think her brain works well enough to recognize trends, one would think that the darkening gradient between alabaster Hopkinton and ecru Boston would gratify her, symbolizing as it does the lessening grip of whiteness on already tiring and beleaguered runners.

I sometimes wonder how my life would be different had I never noticed, let alone taken part in, this elderly New England wobble-fest. Held on roads snaking through increasingly crowded people-centers where almost no one can properly pronounce words, the only thing the race ever had uniquely in its favor was its antiquity and its stringent standards for entry.

If I had never run the Boston Marathon, or at least possessed no good memories of it, I wouldn’t care about the littering of the Boston Athletic Association with the same idiocy now saturating every major Western organization, corporation, and institution. But I also wouldn’t have a trove of interesting memories.

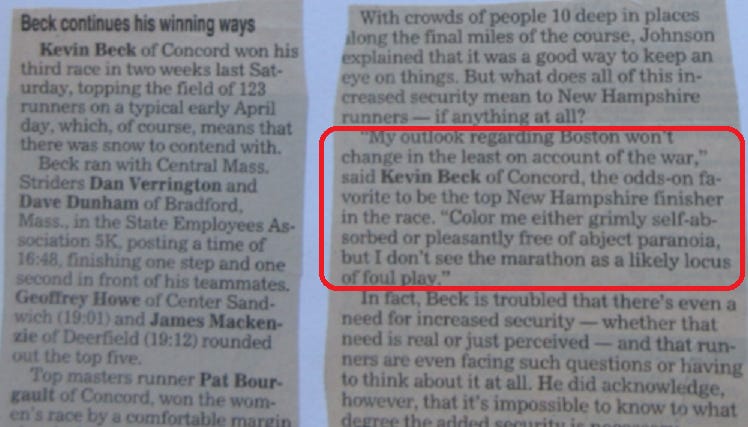

Dave Dunham, a far better scrapbooker than I am, recently sent me portions of an article in the Manchester Union Leader, New Hampshire’s largest and funniest newspaper, that ran shortly before the 2003 Boston Marathon.

The context is that I had been the top New Hampshire runner at Boston the previous two years, and had run 1:49:46 alone in a 20-mile race in the rain in late March during a 123-mile week. I was probably ready to run 2:22 (then the Olympic Trials standard) on a decent weather day.

The 5K was run on an ice sheet covering access roads around the State of New Hampshire office complex in Concord. I had set the course record of 15:27 in 2001, nine days before running 2:24:17 at Boston, but my teammate Eric Morse had broken it in 2002 with a 15:20. I was hoping to get the record back, especially with two guys in the race who were at least as capable of breaking it as I was. As you can see, we were only about 90 seconds shy. Not noted in the write up is that I was chosen as the designated winner during the race because I lived in Concord, which is probably a standard convention.

I had forgotten about my comments to the UL about the threat of something going bad in Boston as a result of the U.S. recently having invaded Iraq. The Boston Marathon had instituted new security policies as a result, which affected runner bags and a few other transportation issues but would have seemed trivial or unnoticeable compared to what’s in place now. Given what happened in 2013, it makes me somewhat uncomfortable to look back on my attitude of “What can you do but ignore that stuff once you’re committed to being there?”

Anyway, the Patriots’ Day struggle remains as real as ever. You can watch it online on ESPN.com, with the livestream starting at 8:30 a.m. Easten Daylight Time, although television sets remain an option for many viewers.