Tommy Atherton's remarkable 1970 cross-country season

How a young man's despair and a legendary motivator combined to give a running dynasty its most memorable – and weirdest – championship

Concord High School in New Hampshire has rolled out some pretty good boys’ cross-country teams lately, racking up a fourth-consecutive Division I state title last fall. In 2017 and 2018, the Crimson Tide—probably as cancel-proof a mascot as any—also won the statewide Meet of Champions held on the weekend after the divisional meets, falling in the last two campaigns to one of the best squads in the Northeast, Division 2 Coe-Brown Academy.

Before its current run began in 2017, though, Concord had been on a long winless streak. Its last D-1 title had come thirty-six years earlier in 1981, the last of Bill Luti’s 25 seasons as coach, while the Tide’s last first-place finish at the Meet of Champions—a status poorly recognized at best until early in the current century—had come in 1987, my senior fall. (In 1986 and 1987, Concord was second to Pinkerton Academy at the D-1 meet. Last summer, I wrote about my close connection to the 2017 through 2020 CHS teams.)

But long before that, Concord High was the team to beat not just in New Hampshire but around the region. By “region,” I mean the six states that make up New England and represent a unique American phenomenon in their being treated as a standard geographical unit. As such, it has a number of different athletic championships at the high-school and collegiate levels, and getting to the cross-country champs, as an individual or especially as part of a team, has always provided an extra bit of incentive for kids with no shot at national-level meets to be race-sharp well into November. (The top six teams and anyone in the top 25 not on a top-six team qualify for the New Englands.)

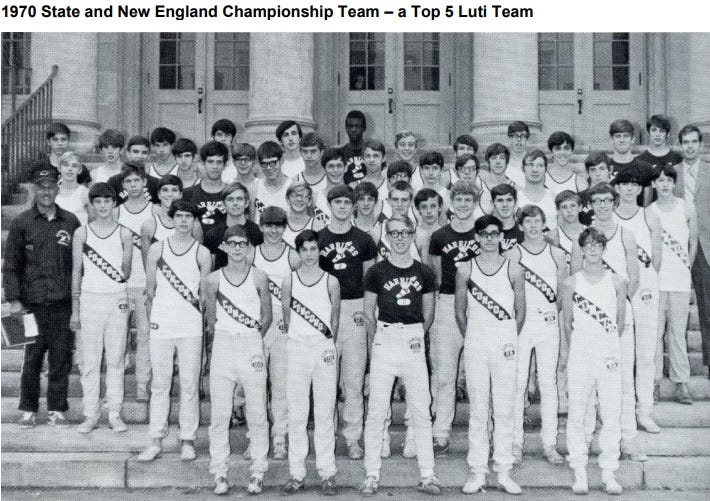

Coach Luti, who took over the CHS cross-country team in 1957 and was mother’s physical education teacher some years later, almost immediately built Concord into a reliably dominant force, guiding the Tide in 1959 to the first of its 13 state D-1 (then called Class L) and four New Englands titles with Luti at the reins. To appreciate the entirety of his impact on the school, the community, and an uncountable number of people generations apart who continue to run today—and not just boys from Concord—I highly recommend Luti’s Boys, a compilation and testimonial put together by Bob Estabrook (CHS ‘64). Some of the teams during my mother’s era featured close to 60 boys, which had to be at least 10 percent of the available pool in those days. Remember, this was all before Pre and Frank Shorter arrived and running became even remotely cool in the United States.

Bill Luti was a Navy man destined to be a post-World War II coaching phenomenon, and for whatever reason the foundation he chose to build it on was distance running. Though he was retired from coaching the boys’ team by the time I was a freshman—he returned to coach the girls to a state title my junior year, often scolding me and his number-two runner for reportable behavior I now vaguely regret in the back of the bus on the way home from meets—I never would have started running myself had his impact on the community not been what it was. My mom suggested I go out for the team in 1984 based largely on how she remembered the experience having transformed some of her classmates at the same school. And later, in my adult life, I privately relied once or twice on Bill Luti, whose entire persona I did not embrace but who was incredibly skilled at setting people straight without an ounce of human contempt, to set me straight on some bullshit I had thought myself into.

But that is all for another reminiscence. Heading into the 1970 season, Concord was the three-time defending D-I champion and had won seven of the last eight state titles. A youngster named Tommy Atherton was heading into his senior year having just unexpectedly lost his father over the summer.

As a junior, Atherton had been Concord’s fifth runner at the State Meet and its sixth at the New Englands, where Concord placed fifth. He started his senior season fighting to be in the top five for the Tide, which would finish the season as one of the strongest of the extraordinarily strong teams Luti fielded during his tenure.

Atherton had made his way up to the third team spot by the last dual meet of the season. But at the State Meet, he outdid having outdone himself, part of a season-long determination to not just resist collapsing in the face of his father’s death, but mold it into a reason to quietly push himself and his teammates harder. Having never sampled the light of the winner’s circle before in his life, Atherton, ever the cagey come-from-behind sort, pulled out a win in the 2.5-mile state championship race—5K would not become the standard distance until the mid-1970s—over Richard Osborne of Winnacunnet, prevailing by one-tenth of a second after an extended homestretch battle. Concord’s other top runners took 3rd, 4th, 5th and 10th to give the Tide a mere 23 points and an easy win.

If Tommy Atherton grabbing the first individual victory of his life at a state-championship meet by the narrowest of margins in a contest also won by his team seemed like high drama, this was all just a table-setter for the weirdness that ensued at the New Englands the following Saturday.

The meet was supposed to be held at Franklin Park in Boston, but owing to what sources describe as “civil unrest” (I’m thinking a war in Southeast Asia had something to do with this), the meet was moved to the other side of Massachusetts on an ad hoc course. I will draw from a pair of Facebook posts by Alex Vogt (CHS ‘71), Concord’s eighth runner that season and therefore a New Englands spectator, to describe the events of November 14, 1970 in West Springfield, Massachusetts, about the time I may have been trying to attempt my first walking steps. I have bolded sections I find particularly instructive:

The day was cool and seasonal. Coach suggested bringing short spikes as it had been raining the previous day. We arrived early and the team walked/jogged the course.

It was an exciting start and I could see the pack of runners circle the field below the hill. The runners came up the hill and our top runners were near the front, so we needed a good performance from our 4, 5, 6, and 7th runners.

The runners came up the hill and circled some athletic fields. Dave Fowler from RI was leading the way by about 10 yards with about 1/2 mile to go. He was followed by a large pack of about 10 runners right behind. He missed a turn on the field and went straight towards the finish. The turn was only marked with a cone, with no one directing, and the pack started to follow him. Lee [Hafeman] was about two strides ahead of Tom and Dan [Tromblay]. Tom was the first to turn right and shouted to Lee: “This way.” Lee hesitated for a stride, then turned and followed along with most of the pack.

Confusion resulted at the finish. Tom Atherton originally placed 6th, but the top five runners and a total of seven runners were disqualified for cutting the large corner. William Durette of Cambridge, Mass. received prolonged applause when he refused the first place medal admitting he had also cut the corner. In most sports, you don’t get this type of honesty. There was some call to redo the race, but in the end Tom Atherton was declared the winner — the second race he had won.

Concord was declared team champion, their fourth New England championship in nine years.

Alex followed this up by getting in touch with Dave Fowler, the first runner to cross the finish line on that day over 50 years ago. Vogt and Fowler were adversaries of a sort at the New Englands, but one year later became teammates at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Fowler, who has evidently run the Boston Marathon over 20 times, shared his account:

As it turns out, I remember it pretty well. I was there on my own as my team didn’t make it. I joined another team for a brief explanation of the course, but we didn't walk it. If I remember right it was two loops starting on the upper fields and circling down to the lower fields, then finishing in the stadium. I had a bone spur on my heel, so I was running in shoes with the heel cut out and the shoe taped to my foot. It may have helped me as the lower field was pretty muddy and I remember seeing shoes stuck in the mud on the second loop.

The issue with the course came up at the end of the first loop as we came up on the starting line. For some strange reason, I was way out in front, and when I came back to the start I proceeded straight across the field. Apparently, we were supposed to turn and go around the field, not across it.

Here's where it gets a bit confusing. At some point, a judge jumped in and started directing the following runners around the field. Depending on whose account you listen to, it was after 10 to 20 runners. I was oblivious and just continued on to the finish. I found out afterward that they had disqualified the first six runners (all from Rhode Island) but when they tried to name the seventh runner to cross the line the winner, he said he had gone the same way as the others.

At that point, they cancelled the awards ceremony and published the results later. One of the judges sent me the official results later, and they listed all the runners as they finished but put an asterisk next to the first seven runners, signifying that they were disqualified.

Alex’s additional insights about the screw-up:

As I mentioned, the turn was only marked with a cone. A judge did not jump in — it was Tom Atherton who started going the correct way and shouted to Lee Hafeman “This way!” I think the judges only got involved after they saw seven runners going one way and the rest of the pack going another. A race like this should have had competent officials directing each turn or had the route roped off.

It was disappointing that the race ended this way. We never will know if Tom may have caught the leader as he had done the previous week. Regardless, Concord clearly had the best team that day.

Atherton would go on to be an all-conference runner for Plymouth State College, a D-3 school in northern New Hampshire. He returned to Concord and was a fixture at the Varsity-vs.-Alumni race that started every one of my seasons and which I took part in numerous times as an adult.

Tom Atherton passed away last August at age 67 in Manchester, New Hampshire as the result of injuries sustained during an early-morning walk. He had been forced to give up running in recent years, but continued to keep fit and make the most of what he had. He was used to that.

From what little I remember of him from passing, long-ago encounters, he seemed like the kind of guy who would give you the shirt off his back without telling you that it had come from a state championship meet, or that he had won the race in question. He was one of a number of seeming old coots (then in their thirties and forties) who showed up at the Alumni race with the quiet understanding that a bunch of 14-year-olds who were about to run their first-ever race were pretending not to be terrified, and offered just the right mix of encouragement and jocularity on the line.

New Hampshire Running posted a nice tribute after Atherton’s death.

Bill Luti died in December 2019 at the age of 98, having outlived a good many of even his hardier charges and keeping in touch with an entire loose network of Concordians across the span of time. The premier road race in the city (of 45,000, granted) is one he started in 1968, then known as the Concord Five-Miler but renamed the Luti Five-Miler in 1984, the year before I first ran it (in 30 minutes, 54 seconds). He was always there in a cowboy hat to fire the starter’s pistol, and always at the two-mile mark giving splits, and whether you were 14 or 41, you just wanted to impress him, not by beating anyone but by honoring the effort and realizing that the race, any race, was just a small step in a much greater path. That’s always true of any of us, but Bill Luti made you consider it, and never from precisely the same angle. That’s real coaching.

It is easy enough to imagine, without descending one step into mawkishness or Lifetime Channel-ready cliché, the dynamic in place during the 1970 Concord cross-country season: A boy loses his father going into his final year of high school, but has one last great thing to give to a coach he and his teammates already see as a father-figure; the coach has an uncommon level of paternal concern, and real love, for everyone under his care.

Every mid-sized town has a figure or two like Bill Luti, and they only happen along— they can’t be replicated or coerced out of ordinary human substance, especially nowadays. Despite the progressive scarcity of the breed, and its occasional resistance to various aspects of modernity, I hope you know someone like him, and keep him or her and their wisdom and lessons close.

The 1970 season proved to be the approximate midpoint of Luti’s coaching career and, despite ferocious competition from both sides of the calendar, arguably its pinnacle. Neither of the main characters in the core event of this story— featuring a blend of grace, grit and absurdity seemingly found only in cross-country running—could have played the role they did without the other. And without figures such as these, including the friends and ancient-but-not-forgotten rivals who supply these kinds of old-old-school memories so that I can pass them along myself, competitive running wouldn’t be what it is.

Not for me, at least.