Topological doping and other hijinks

Toward the beginning of the year, I decided I'd allow myself to post here only after producing a new running-related article for a paying entity. I expected this constraint to reduce my blogging to practically zero if I stuck to it, because between my other work and my unusually far-ranging travel plans, I didn't anticipate doing much writing about running, period.

But as is the case for a substantial number of people, the middle of 2020 doesn't look like January said it would. I also realize every time I work with certain people that I ought to do more of it. On top of that, things happen.

I've generated two clickables for Podium Runner this month. This one describes a really helpful and efficient workout, insofar as anything we recreational runners do to get faster can be regarded as a wise use of personal capital. I think I got the idea for it from Daniel Komen in the late 1990s after reading that he'd done it in 3:56-2:55-1:56-56 or something close to that, though I'm not sure of the rest. I ran it in 4:47-3:32-2:17-61 in 2001 not long after my 2:24 marathon, but the rest was probably more like three minutes because I was pacing a high-school kid, and you know how they are between reps, finding excuses to re-tie shoes, rearrange their crewcuts and so on. He went on to win a second state title in the 3,200 meters a couple weeks later, and ran his high-school best of 9:26 a week after that.

This one, meanwhile, details a workout I've actually myself more than once within the past several years. In fact, the hill in photo, taken by editor-in-chief Jonathan Beverly -- and though it would be fun to lie, not for this piece -- is the one I used. You can almost see the 0.9-mile-long path around little Viele Lake off to the right in the backgr, although not for this piece. In the next week or so, two more should appear. One is a review of the careers of four runners, only one a UVM graduate, who returned from long absences -- and various compelling reasons to stay quit -- to match or arguably exceed their already considerable achievements. I'll also have something about combination workouts after picking this guy's busy brain a little more.

For now, though, I'll return to the topic of hills. I do this with both reluctance and the usual demonic joy that accompanies deconstructing the sort of antics that manage to be dishonorable and hilarious at the same time, like one of Frank Gallagher's schemes but without the felonies and misdemeanors.

For the first dozen or so years of my running, ending around the time of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, bullshitting was the one thing that would quickly get anyone razzed to the sidelines of the sport. Even most people known to possess large moral vacancies in other areas of their lives could be counted on to give accurate information about their workouts and races -- even though, pre-Internet, the only media carrying local and regional results in my region were Boston Running News (a monthly that later became New England Runner) and in the Sunday Boston Globe. If you showed up to a road race and got an accurately measured course with splits, water, and a cotton T-shirt, you had received all you wanted for your $10 or so -- still far cheaper than a 5K today after factoring in inflation. And if you were a pain in the ass like me, the Keene State College guys who would laugh their way through 25-minute summer five-milers would let you tag along on cool-downs.

The idea that running would mushroom into what it is now -- and whatever you instantly imagine when you picture a big-city marathon from about 50 feet above the fray works -- wasn't on anyone's radar, because no one foresaw the idea of many thousands of people training for marathons in the late 1990s as part of self-actualization quests, many of them in no hurry as long as an appropriate medal awaited them at the finish. For this reason, no one saw the economics of road running being newly driven by the goodie-bag and turning a lot of events into roving concerts with all-you-can-eat buffets at the end. The entire atmosphere started to smell more like a contest to see who'd been manhandled by life before making it to the event than a contest with one's self to cover the distance between the starting and finish line. But if more of the public suddenly wants to participate in races, then the providers of those races are naturally going to offer an experience that on average dismisses with much of the need for the ostensible basics, like properly measured courses.

Once cell phones, GPS watches, and social media -- especially data-sharing platforms such as Strava -- had become near-universal in the running world, it was inevitable that a certain fraction of the running population would combine these tools to make asses of themselves in countless ways. After all, consider the reactants: A whole set of new tools for self-promotion, a running demographic that had grown far out of proportion to the nation as a whole, and a generation of people who, in the main and God bless every last one of them, grew up believing that absolutely ordinary feats by ordinary people needed to be elevated, memorialized and propagated as widely as possible. Some people call members of this cohort Millennials; I call them the kids of my friends, which was apt to go to shit in a hurry no matter what because I know these people.

Actually, that's all pretty facile. What I'm really trying to do here is pad the blows in advance because I don't think the world in which today's younger adults were raised was ever going to produce anything other than a good deal of what it has.

The topic of net-downhill road courses is a contentious one in the sense that while they clearly aid times, it's hard to say exactly by how much, especially since a net-downhill course almost has to be a net point-to-point layout and can therefore feature a net following wind, usually the bigger factor if it's even a few miles per hour in magnitude. And downhill mile races are nothing new; most people have probably wondered how fast they could really go with a gravity boost, and there's no harm in feeling good about the result, in context. The Millennium Mile in New Hampshire has been around for over twenty years has hosted multiple sub-fours. But I don't know many people who consider times run on such courses to represent personal bests. I mean, it's not like running logs are a threat to ever be seized for auditing, and people can decide on their own definitions of "legitimate performance." My own marathon PR was run on an aided course, so it gets an asterisk from both me and T&FN, even though there was supposedly a very slight headwind in Boston that afternoon and I could produce all of the rationales in the world for why the drop on that course is actually a detriment.

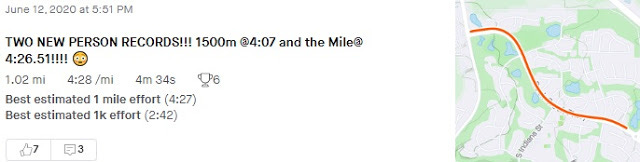

But purposefully downhill races are one thing. In these, everyone gets the same boost and, more importantly, no one can lie about the course profile. But the covid pandemic has spawned a lot of solo time trials and attendant braggadocio. The one below is an unusually glaring example, but the phenomenon itself isn't what I'd call rare.

The first thing that might jump out at you is the idea of deciding en route to turn a 1,500-meter time trial into a mile. On a track, there would be no finish line -- you could run the opening straightaway a fourth time and wind up with a 1,600 meters to your credit, but to run a mile accurately you have to have a track with the correct markings. Also, those of you who have actually raced these distances know the odds against someone really opting to turn an all-out 1,500 effort into a mile.

But this wasn't on a track. The author happily advertises that the run took place at 5,600' above sea level, but a more useful description is that the start was at close to 5,620' and the end was about 180' lower. This is revealed by the Strava data for the run, which shows that the route used was that of the Superior Downhill Mile, ordinarily run every 4th of July.

In addition to concealing -- or to be charitable, failing to note -- the elevation drop on Instagram, he also seems to have jiggered the data to impart even more false excellence to his effort. It looks like his watch read 1.02 miles after he ran the course -- certified and marked on the road every 440 yards -- in 4:34. So he took the liberty of lopping off the 0.02, creating an illegitimate 4:28. Then, it seems, he used additional Strava padding mechanisms to get this down to 4:26.51. (It also strains credulity that this road-run started out as a 1,500-meter time-trial and included an accurate 1,500-meter split, but that seems kind of like adding a parking violation to a hit-and-run just because the cop is allowed to.)

I'm not surprised that people do this kind of stuff; the running world has never been free of flamboyant liars -- Google "1980 Boston Marathon" for a possible example. I'm just nonplussed by the widely accommodating general reaction. By the time I saw the Instagram post, it had received over 150 likes and lots of "Attaboy!" input, but no mention at all of the fact that the poster was being actively deceptive. I saw the names of the commenters, and a sizable fraction of the audience was well aware that the entire shooting match was nonsense. So I decided to balance the scales incrementally.

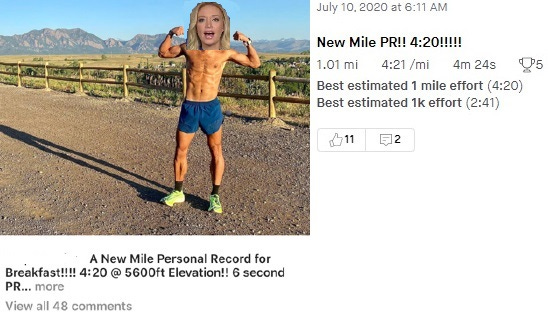

I don't know how long my comment survived or if anyone replied to it, but when I checked the next day it was gone. I believe that by any standards and especially my own, it was perfectly diplomatic, but people use these platforms to be fellated, not berated or even advised. And if he was in any way cowed by the temporary exposure of his ruse, it didn't discourage him from repeating the same stunt on the same course four weeks later.

You can see that he's shaved what looks like four seconds from the recorded time for the Superior Mile course -- 4:24 became 4:21 with the apparent jiggering, and that got rounded down to 4:20. That's only half of the eight seconds he removed from the June 12 run, so that counts as progress of a sort.

The question of how much faster this course runs than a track at the same altitude is interesting but moot for the time being. But this is someone who's run a couple of low-2:40s marathons and commensurate times at other distances, and would probably have a hard time breaking 4:40 on a track about 5,000'. Even guys who are well under 30:00 for 10,000 meters at sea level struggle to run 4:20 for a mile (or under 4:00 for the 1,500, approximately the same achievement). Obviously, the idea would be to get this guy and his clearly improving fitness into a mile track race and see how he fares, but apparently he's already been challenged by one of the top local women and declined, citing some combination of the altitude and health concerns. I'm pretty sure most people are susceptible to these concerning altitude effects as well; they reliably cost an athlete about 2.2 percent over a mile race at CU's Potts Field (5,260'), roughly seven seconds at 5:00 pace.

Running a downhill times and framing them as something else is, to me, evidence of insecurity, not moral leprosy. But either way, it's something people should be discouraged from doing -- ideally by their friends, not as a result of third-party mockery. In fact, the first thing I think whenever I see this kind of behavior is that whoever is behind it isn't long for the world of competitive running. But I can't confidently say even that much, because this fellow is not the only local pulling this stuff; even a local Olympic Trials qualifier has apparently been caught massaging the data from a downhill effort. I have come to strongly suspect that, in addition to just wanting to look better, some people run downhill races and time trials because they believe that eventually, they can somehow reproduce those times on the flat. After all, they're still moving their arms and legs at the right rate, aren't they?

Scott Douglas, another OG running observer whose interest in this probably arises from curiosities much like my own, interviewed a guy in 2012 who wanted to break two hours in the marathon. Between 2001 and 2007, Hobie Call ran four marathons between 2:23 and 2:25, all on aided courses at moderate-to-high elevation. Call is clearly a physical badass who has won a slew of Spartan races, physical challenges that I'm sure would make even a slightly uphill marathon feel easy. But he was completely and utterly delusional about the effects of downhill running on his and other people's times.

An international series of races now exists precisely to offer illegitimate marathon and half-marathon personal bests to people who are willing to tolerate the leg-pounding and attendant likelihood of injury in exchange for Getting Likes that underwrite aided times and lead at least some participants to believe that these times accurately reflect their abilities. The organizers try to make the series largely about something else, but everyone knows why people flock to these joke events, however beautiful the scenery may in fact be. And these courses claim victims, though some remain perfectly content in the aftermath. This guy, pointed out to me by the same sadist who knows exactly how to trigger me in other areas, is my favorite example of a somewhat explicable social-media running superstar. He's relentlessly positive and unapologetically addicted to running. He has almost 24 billion unique followers, or soon will. In 2018, he ran a huge PR in a downhill half-marathon in Utah, and was hoping to break 2:40 ar at least 2:45 in Chicago a few weeks later, but it didn't come together. He doesn't seem entirely sure what happened and neither does anyone else who follows him regularly. I have nothing bad to say about him, but I still can't get used to the amount of fifth-degree buncombe that people just cheer on, mainly, it appears, so that they themselves can get the same accolades for the same middling shit.

Whatever tickles your bits, I guess, but at least be up front about it. And anyone who thinks I'm raining on someone's parade here obviously doesn't understand what parades are for. If you use social-media lies to extract praise from as many faceless yutzes as possible, it's acceptable for anyone who happens across this material to evaluate whether the praise should be balanced by at least a homeopathic dose of reality.

What else? I rarely go a day without technically working, but for the most part I'm coasting along deciding where to focus a plurality of my available energy. My mom is hoping to make it to Colorado this fall (she was scheduled to arrive in April ). I'm not going to Europe this year, but I did make it to Wyoming recently. I spent a few days up there with a friend who's an environmental scientist with an energy company installing a gigantic wind-turbine farm up there, and I got some nice pictures out of it. It's clear why no one wants to live in the parts if Wyoming I explored -- a breathtaking environment doesn't compensate for an unbelievable amount of wind. But I got to do some real four-wheeling in an F-250 (a change from my everyday douche-wagon) and Rosie was allowed to come to help count prairie-dog holes, and it was actually a blast.

My everyday interactions with randos have become more quietly fraught despite my own rosy disposition, because like everyone else, I'm tired of people not interpreting suddenly imposed rules and norms precisely the way I do. A certain low but non-negligible fraction of people, most of them well past their nominal expiration dates as biological entities, are convinced that they can be corona-fied by a jogger from 50' away no matter which way the jogger's face-pores are turned, as if heads can disperse viruses in an expanding sphere, like omnidirectional radio-wave beacons. Between the heat -- and even 75 is warm for a dog with a dark coat -- and the crowds on the paths near me, I've started doing my substantial run of the day at about 8:30 or 9:00. I don't think I've missed a day this year, though I'm not sure; I know I run every day that it's possible because it improves my life, and I'm pretty sure it's been possible for the past 200-plus days. I haven't run for even an hour at a time since Christ was in diapers, though, and frankly am having a hard time wondering why anyone would.

Since March, I've become a part of two joint writing projects that may go nowhere but give me something to do and give me a sense of goal-orientation, which I seem to require despite having no identifiable long-term goals and understanding that there is nothing wrong with this.

You can see from these end-notes that nothing in my life, including my inner monologues, is interesting enough to justify writing about. I'm not even moved to describe my nonexistent sex crimes and acts of vandalism in the park up the street anymore, especially now that people are actually doing that stuff and I might wind up accidentally confessing to a genuine crime. Part of this shift is the result of discussing emotionally resonant issues, good and bad, with my friends more often than I did pre-covid, and by "discussing" I mean forming and expelling words using my face, not my fingers. This leaves even less reason than usual to involve any of you feckless fart-sniffers in my psychodramas. But if you must, imagine a middle-aged jogger with a cute dog whose lifestyle resembles that of a widower on Ritalin, and who sees more or less the same scenery every mostly sunny day. You probably knew someone like this when you were a teenager and wondered why he still bothered, aghast at the prospect of becoming one of those shambling, knock-kneed goofballs yourself in a few decades. It's actually more fun that he lets on.