Two world track records, one old and one ancient, fell last week

Daniel Komen's indoor 3,000-meter mark was ripe for the plucking. Not so for any of Jarmila Kratochvílová's musty marks

On Wednesday, Ethiopia’s 22-year-old Lamecha Girma broke Daniel Komen’s 1998 indoor world record of 7:24.90 in the 3,000 meters by a clean 1.09 seconds at the Meeting Hauts-de-France Pas-de-Calais in Liévin, France. Mohamed Katir of Spain also went under Komen’s standard with a 7:24.68.

Girma, who has also ducked under eight minutes three times in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, entered the competition with a personal best of 7:27.98 from the same meet two years ago.

This was not a surprise—in fact, I figured the record would go sometime last winter. Komen was a generational talent who was surely drowning in EPO, which is no match for the relentless production of new human capital, faster tracks, superior footwear, and the reliable persistence of performance-enhancing drugs. I thought Yomif Kejelcha, who holds the indoor world record in the mile (3:47.01 from 2019), would be the first to break Komen’s indoor record. (Here’s the all-time indoor 3,000-meter performance list.)

Komen’s outdoor record of 7:20.67 is in similar danger (all-time list). Technological improvements to indoor tracks throughout the current century seem to have outpaced gains made to outdoor tracks, which makes sense given the physics involved. This has drawn down the difference between indoor and outdoor times, meaning that an indoor 7:23.81 isn’t as close to a 7:20.67 outdoors as it was in the late 1990s. But that doesn’t really matter, especially because it’s easy to foresee multiple athletes taking a realistic and concerted shot at 7:20.67 this summer (Komen ran the last kilometer-plus of his outdoor world record alone).

On Sunday, Femke Bol of the Netherlands, also 22, broke Jarmila Kratochvílova’s 41-year-old indoor record in the women’s 400 meters with a 49.26, 0.31 seconds under the Czech athlete’s 1982 mark. She did this in her home country at the Omnisport meet in Apeldoorn. Four women, or athletes competing as such, have now dipped under 50 seconds for the distance indoors.

In 2017, The New York Times essentially called Kratochvílová the dirtiest professional woman track runner of all time. Whether she was merely doped to the point of bursting or possibly “intersexed”—the latter idea bandied about over the years but unconfirmed and probably unlikely—is irrelevant, because no serious observer believes that any of Kratochvílová’s records are legitimate, including the 1:53.28 800 meters she ran in 1983 at the age of 32.

On Sunday, Letsrun.com’s front page linked to a message-board thread about the record, with a mention of U.S. superstarlet Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone.

LRC is referring to the fact that Bol’s specialty is the 400-meter intermediate hurdles, in which McLaughlin-Levrone holds the world record (50.68) and Bol is a distant third (52.03) (all-time list). Bol’s best outdoor time in an open 400 meters is 49.44 from last summer, and her world record on Sunday was an improvement of 1.04 seconds on her previous indoor 400-meter best, which she ran at last year’s Omnisport meet. McLaughlin-Levrone’s open 400-meter best is 50.07, but that’s from way back in March 2018, when she was 18 years old.

The implication is that Bol may now be a lot closer to McLaughlin-Levrone’s ridiculous 400-meter intermediate hurdles world record of 50.68 than anyone thought.

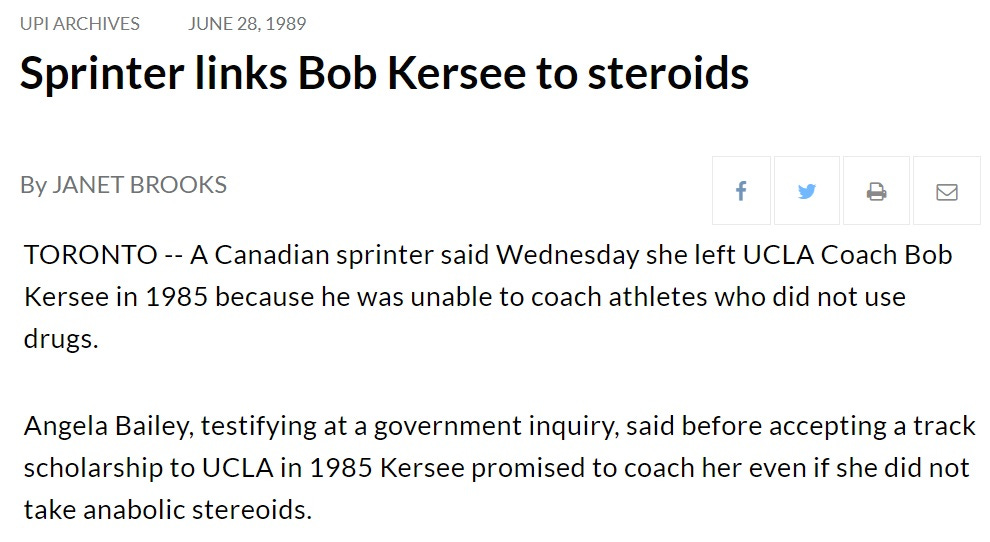

Since Bol broke a spectacularly suspicious record, and we’re* already discussing doping, it’s worth mentioning that McLaughlin-Levrone’s coach is Bob Kersee, who also works with Athing Mu. Kersee, as you’ll see, is especially adept at pouncing on young American female megatalent.

In September 1998, not long after the Festina doping mess at that summer’s Tour de France, Merrill Noden wrote an essay for Sports Illustrated imploring track and field to address its doping problem, citing the cases of sprinters Ben Johnson, Dennis Mitchell and Harry “Butch” Reynolds; shot-putter Randy Barnes; and distance runner Martti Vainio, an unusually delicious example. (Mitchell currently coaches Sha’carri Richardson, who last raced in September and has had some public struggles lately; both were glorified on a recent Citius Mag podcast, along with fellow formerly suspended-for-doping sprinter and current Mitchell trainee Justin Gatlin.)

The column includes this line: “If a sprinter ever does run a 9.79, of course, fans will automatically assume that he has been using performance-enhancing drugs, whether he has or not.” Ten men have now run under 9.79; many served suspensions for doping, but the world-record holder, the retired and suddenly impecunious Usain Bolt of Jamaica (9.58), never did.

One name not mentioned in Noden’s piece: Florence Griffth-Joyner. “Flo-Jo”—who set still-standing world records in the women’s 100-meter dash (10.49) and 200-meter dash (21.34) in 1988—died in her sleep at the age of 38 just two weeks after the SI piece was published.

When Flo-Jo died, talk immediately turned to her not-very-secret—although technically rumored to this day—indulgence in performance-enhancers, which was no rarer in the 1980s than it is in 2023. It can’t be known if steroid use contributed to her death, but all the angry comments at such innuendo from track-and-field types at the time were a deflection from the fact that virtually no one who was around in those days thought Flo-Jo was clean:

While many celebrated her career of super-fast times and attention-getting fashions, few could forget the 1989 controversy after a German magazine reported drug allegations by Darrell Robinson, a 400-meter runner from Tacoma. Robinson, a state champion at Wilson High School, said Griffith Joyner asked him to buy growth hormones for her and paid him $2,000 in $100 bills. The human growth hormone can promote muscle mass and is undetectable.

When Flo-Jo passed away—an event that was tragic from every possible angle in addition to pecking at not-yet-healed scabs on the sport, as she had a seven-year-old daughter—USA Track and Field CEO Craig Masback, who had taken over the position in 1997, said: “Her success ushered in an age of cynicism in track and field where people could not accept performances for what they were and were always looking for another explanation.” That’s not really a denial of anything, and in fact is quite craftily put, even for a licensed attorney.

Masback, a 3:52 miler, was a major reason I got excited to watch track and field on television as a teenage running-nerd. He was fantastic with a mike in his hand, low-key and wasting no words, and in 2002 he also co-founded the USATF Foundation, which in theory helps check current USATF CEO Max Siegel’s “faster, higher, stronger”-themed avarice. He was, in my squinting judgement, also a great CEO, especially when I squint retrospectively. But during his approximately eleven-year tenure at USATF, Masback dealt with the unpleasant career-ending suspensions of Regina Jacobs, Marion Jones, and other very big, very marketable names.

During the Jones fiasco, Masback defended USATF’s approach to banned substances, noting the USATF had pioneered the out-of-competition testing of top-level athletes across sports governing bodies. But after BALCO babe and breakout sprinter Kelli White was banned for a positive modafinil test in 2004, Masback’s tone implied he’d gotten used to the mundanity of the mundane: “It's tragic any time an athlete makes a choice to cheat, but we are glad Kelli White is taking responsibility for her actions."

For a while, Flo-Jo’s coach, as the Seattle Times piece notes, was Bob Kersee. Back in the day, Kersee also coached his wife, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, then the most accomplished heptathlete in history. “JJK” was asthmatic, and she admitted to taking the generally banned corticosteroid prednisone at times to deal with flare-ups. Kersee said JJK “never took a banned medication when she was competing.”

Flo-Jo and Kersee reportedly parted on poor terms in 1987, after which Flo-Jo was coached by her husband Al. That was two years after a Canadian sprinter left the women’s track team at the University of California at Los Angeles because Kersee, the team’s then-coach, allegedly had members of the UCLA team on steroids, with those who declined unable to handle the workouts.

By associating herself with Bob Kersee, McLaughlin-Levrone is ensuring two things. The first is that she will continue to run very fast times, possibly between injuries and “injuries.” The second is that Kersee will make sure that McLaughlin-Levrone—who will never risk a doping positive as long as she’s with Nike—will, like Femke Bol, always be on the best available performance-enhancers (unlike this Bol, at the moment unsuspended and probably not a close relative).

Whenever she hits the track knees-first after another surreal effort, ostensibly directing her prayers heavenward, I have to wonder what single gift, if any, McLaughlin-Levrone is most thankful for in these moments of theatrical exaltation.

Also from Noden’s 1998 SI essay: “A 70-foot-plus shot-putter once told me that he believed no one had ever thrown 70 feet without an artificial boost; the human body just isn't built to do that any more than it's built to race over the Alps day after day on a bicycle.” That’s as quaint as quaint gets; on Saturday, American Ryan Crouser broke the indoor (and absolute) world record in the shot with a toss of 76 feet, 8.5 inches.

Nothing—not poignant columns by esteemed sportswriters, not the sharp and well-intentioned leaders of athletics federations, not dire warnings to the young about the health risks of exogenous androgens—will ever stand in the way of world-record progressions in track and field. The arena of combat is not popular enough to survive without them, and the world is far more tolerant—even loving—of scandalized sports and imperfect icons than of boring ones.