What's your personalized interface with distance running?

If you feel glued to running even when it's gone nuts or is kicking you around, you may want to thank your skilled and tenacious mediator

The typical feedback-providing reader of this blog is, like me, a distance runner, one whose initial exposure to the activity was competitive. If they don’t have a high-school or college team singlet balled up somewhere in a closet, then something prodded them to take up running as a sole aerobic proprietor at some point in adulthood, and they soon became captivated more by the prospect of becoming a maximally proficient athlete than by the social aspects of the events designed for the demonstration of that proficiency.

Runners who show up at races mainly to race hard, however, tend to lose interest in this after a couple of decades even if they haven’t battered their legs and joints into painful submission, and may in fact come to avoid the whole ever-more-clamorous road-race scene altogether. But being committed competitors, most of these one-time 10-plus-miles-a-day zealots still maintain unyielding contact with the sport as coaches or merely as observers who continue to jog.

If this describes you, and you do still race, you may not be out for blood anymore, consistently or at all. But no matter how fast you are or ever were, there was perhaps a time when you wanted to beat everyone in sight, a period that ultimately launched what have become your most powerful running memories—and rightly so; working hard to surpass your peers or betters, no matter what the world offers you as a reward for doing it, is an unmistakable sign of improving yourself as a runner, and it’s also a harmless way to learn some important things about yourself and your greater motivations as a human. But even if you’re not looking to break finish-line tapes or nab age-group prizes these days, if you do continue to test yourself—even if only on the sly—then it’s a safe bet that when you scan whatever data you collect, your mind can’t help but start imagining workouts you could do to make the same data look more appealing the next time you gather and display it for your eyes only.

So, not surprisingly, striving for maximal improvement or involving yourself in the efforts of others trying to do the same thing are helpful traits for sticking around running for a spell, often a long one. But after many years of observation, I’m convinced that even the combination of these is insufficient to make someone feel like a permanent runner. To me, this identity requires making a tiny sliver of running yours alone, in a way you might be able to describe if you want to—I’m trying—but have no need whatsoever to defend or elaborate on to others.

This is true even for many of those who manage to excel at both running and coaching. Some people—more than you’d think—can train and race hard and honorably as distance runners throughout high school and college without developing any kind of psychological need to run; they cheerfully fulfill the requirements of being on a sports team, and when you see them ten, fifteen and twenty years later, they are fat (or at least without sunken cheeks) and happy doing whatever they wound up doing after competitive cardio became a thing of their past. Others develop a keen interest in running and racing for the first time in their twenties and thirties, often making a quick and sizable splash at the local level but then losing interest after a couple of years once they turn out to be merely good and not great. From this delightful human stew of varied experience has emerged an army of skilled and devoted coaches, plenty of whom never again run a training-oriented step themselves once they make guiding other runners a career.

For some people, this works nicely. As foreign as it appears from the perspective of an all-or-nothing sort who genuinely happens to enjoy moving around under his own vim, these people feel no compulsion at all to run or even feel like a runner after they’ve been dormant for a while, just as you yourself may have once paid very close attention to, say, professional basketball, but now couldn’t name more than two or three of the players on the most recent NBA All-Star squads. Running is simply a sport to some people—I say this without ill judgment, and in fact with some admiration—and in the sports-fan brain, no one sport is irreplaceable. They can think about their stints as runners fondly but without feeling at all “itchy.”

No, to enjoy security and serenity as a runner in the way I’m describing, you almost have to find a way to decorate your personal running-self with the boldest parts of your childhood-plus-adult imagination. You need to discover a way to meld the entire concept of self-propelled motion with various unapologetic extensions of your own ego in ways that stand apart from striving for personal bests and everything else I’ve mentioned so far.

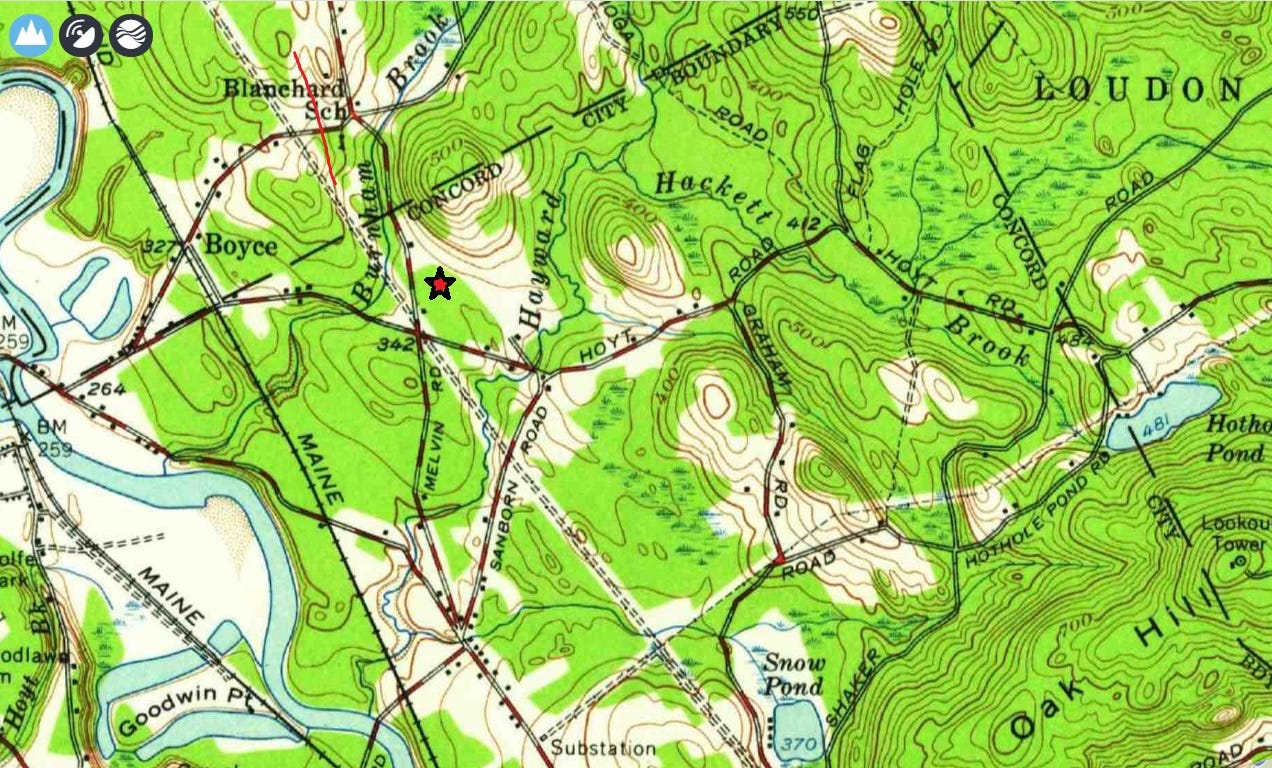

What I’m trying to convey, reduced to a metaphor, resembles an ongoing meeting inside my head between three parties: My jostling bag of psychological needs; the sport of running itself, both its intrinsic demands and my view of its increasingly demented public profile; and my stand-alone fascination with maps and physical landscapes. The first two parties have a close but volatile relationship, with each driven by some combination of cold logic and righteous emotion, while the third is a pure intellectual and stoic who acts as a mediator between the first two. For me, this mediator is a nearly five-decades-long obsession with maps, and I’ll attempt to flesh out the whole “personalized interface” concept with this anchoring my own example.

No matter what else is going on, a stopwatch and an accurately measured course are all the equipment I need to inform me of my objective running worth. It’s up to me to decide how much worth to assign to these efforts, and I tend to be ugly about this. But no matter what, I don’t offer myself the option of lying about the result, and this would be true even if I somehow knew I could get away with claiming an illegitimate performance as legitimate. This isn’t because I’m an unfailingly honest person in every respect. It’s just how I relate to running. I wouldn’t bother with this shit if I had to start pretending I was capable of feats that I’m not, or even if I felt the need to tell anyone I’d run a time that I could almost certainly run with ease but in fact had not. The only cost to this is living in a sometimes unforgiving reality, and for fuck’s sake, what has lying about a running performance ever gained anyone in the longer term?

In the meantime, the sport has changed so much over the decades, and especially since the advent of social media, that even these simple guardrails don’t matter to many of its more aggressive insurgents. In an age of truly perverse self-absorption and skills-free one-upmanship (or “one-upthemship”), the idea among too many is not to discuss having accomplished something, but instead to brag about either a patently false accomplishment or a wildly unrealistic impending accomplishment or twelve. As long as enough people rally behind the illusion, it carries the same legitimacy in certain corners as an actual performance. And a lot of actual runners are actively supporting some of these fuckabouts. So, my bag of psychological needs has grown overstuffed watching this crap and the attendant collapse of running journalism, and obviously comes into direct conflict with the running world’s momentum, if not its genuine needs.

How much these things matter when I contemplate the idea of going running is discretionary and fluid; at least one other thing is not. Call it a linchpin, an anchor, or a guiding light, but the fundamental reason I am fascinated with running—something that has held true even during periods when all I consciously thought about was training as hard as a sensibly or otherwise could so see how fast I could race marathons and other distances—is because it lets me explore Earth at a faster pace, in a way that feels exhilarating, and couple this to a lifelong fascination with all things cartographical. I plan to write a lot about the ways I have used maps to entertain and enrich both myself and others—mostly the first, I’m afraid—but for now, just accept that I started running because I agreed to join a team, but I stayed around because of the maps and exploring, even if this was never evident to other people.

Often in response to my most plaintive existential wailing, people will suggest writing about how elements of the sport that have been sacrificed at the altar of technological progress might not be lost forever, but are still floating around out there in the collective mind of people who are similarly agog at the sport’s shift in priorities at the citizen-entry level. Well, no one has said that explicitly, but that’s what I took from one wise person’s suggestion to write about the totality of the handwritten running log, and how the experience of keeping one isn’t the same, isn’t quite as playfully indulgent, in the age of typed or fully automated data uploads to an electronic storage system. Even people who always enjoyed sharing their piles of dog-eared training logs with as many other runners as demand requires don’t see the Strava and Garmin environments as welcoming, and it’s not because of Strava having morphed into another dispensary of gleefully Wokish lap dances.

Anyway, I am not writing about running logs now, but I decided to turn that suggestion into “write about whatever it is that’s woven its way into almost all of your memories and thoughts about running, was probably there before your started running, and will outlive running in your mind in the unfortunate event something stops you from doing it while you still want to.” For you, it might not be maps, or the giddy, swooning sensation that can accompany looking at your own 25-year-old handwriting in a running log (commemorating, say, the 9-mile run—FARTHEST EVER!!—you did to commemorate finishing the ninth grade). It might be the person in your life, if any, who steered you into running, intentionally or otherwise. It might be something in nature, not unlike my own interface, which I would describe—aside from the running itself—as unequal parts map-following, the unraveling of urban-planning histories and mysteries, and benign trespassing. It could be an indelible memory of an experience that relates to your running in an artistic, emotional, or metaphysical way that only you can understand to your own satisfaction.

As clumsily as I am articulating this, I have a feeling most of you understand what I’m talking about. There is probably something about your running that nothing can touch, that lies beyond the ability of the most obnoxious supervisor or colleague or Internet persona or ex-husband to perturb, even if these things can scramble your hold on your moment-to-moment motivation to go running. There is something stronger in this formula than just the memories of extraordinary feats on the track or cross-country course, and it’s as much a reason for why you live as why you’re grateful for running. Perhaps this largely unfocused rambling has jostled something loose in your own brain, and you’re considering what it is that makes you glad you have this thing in you and hopefully always will, as much as you’ll ever really own anything in your life, even if you can’t put it on Instagram or eBay.

I find it helpful to be conscious of my personally nourished and adorned sense of running belonging and ownership, even if staring at or even thinking about a topo map isn’t necessary—functionally or inspirationally—for me to get out the door most of the time. This offers me a sense of solidity of purpose, and usually distracts me from any unruliness that may have taken up residence in one of my many mental ghettoes. And even though it’s private, the concept itself isn’t, and I think it’s an important one for those of us who gnaw on optional misery in the form of incessant brooding.

As a final note, I don’t observe these things in an effort to establish any sort of moral or belonging-style hierarchy. I’m only trying to relate exactly what has made me feel like a runner over time, and presumably will retain the power to do so in perpetuity regardless of externalities.