Why is the medium-long run so valuable?

Task specificity, versatility of task execution, reliability of effect, and social factors, that's why. If you keep reading now, you're just procrastinating on something else

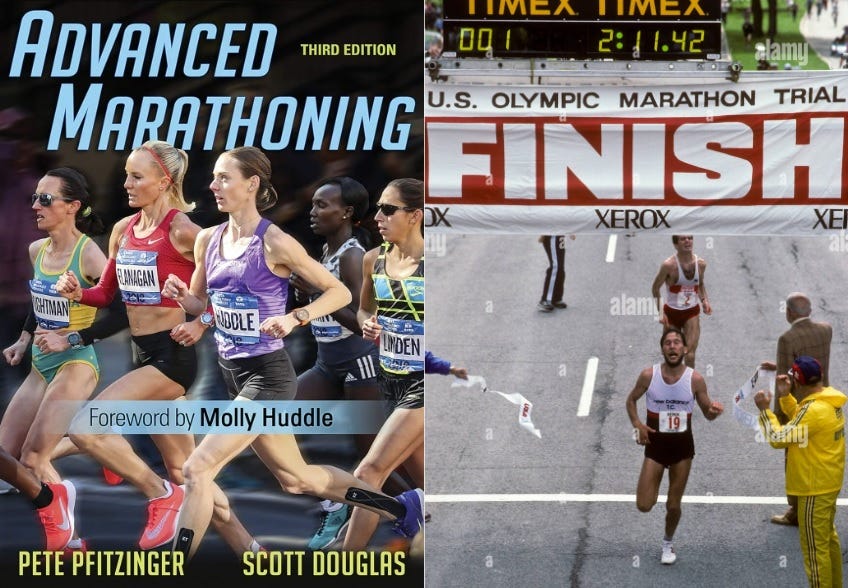

My first exposure to officially sanctioned marathon-training plans that featured a weekly medium-long run (MLR) is owed to a book published in the winter of 2001 by two-time U.S. Olympian Pete Pfitzinger and Scott Douglas titled Advanced Marathoning. My first systematic utilization of the MLR was in the beginning of 2003, when Pete became my coach.

Over that winter, I got into the best marathon and overall shape of my life to that point, as evidenced by strong half-marathon and 20-mile races and a couple of long runs that included enough sustained fast running to offer both confidence boosts and evidence that these amplifications of confidence was justified.

I didn’t deliver on marathon day in April, but the weather was warm, and dropping out was a grim but sane choice. The only American who attained the Olympic Marathon Trials qualifying standard of 2 hours, 22 minutes that afternoon in Boston (the race then started at noon) was a diminutive, Belgian-born supergeezer who was famously busted for doping the following year.

It’s easy to forget that I was doing weekly 14- or 15-milers during this buildup (with a high week of 135 miles) because I was always more consciously concerned about a more ostensibly “benchmark”-caliber workout I had either done within the past few days or was scheduled to do later that week. In the few years I remained serious about racing after 2003, and from observing others since, I grew to appreciate the value of these kinds of runs even more. The only “problem” is finding enough runners willing and able to do them.

Were this an article in a corporate publication, below would be the 4 Secret Benefits of the Medium Long Run (And Why You Need Them). Instead, it’s simply a list of reasons I believe every serious marathoner should, in addition to doing weekend long run in most weeks, do a weekly run of around 12 to 14 miles (or better yet, 90 to 105 minutes) at an average intensity corresponding to at least 80 percent of marathon pace (MP).

Task specificity

Assume that the best way to fundamentally get into shape to run marathons is to cover as much distance in training as possible, with determining how to split up those miles, kilometers, or femtoparsecs being a secondary consideration. This is clearly true to a point, and dictates the marathon performances of most everyday running stiffs.

When you run continuously at an honest pace for over an hour and a half, you’re allegedly training your body to run that pace under metabolic conditions similar to those you’ll encounter in the second half of a marathon race. This doesn’t happen in the everyday “filler” runs that by obligation make up most of a serious marathon runner’s training, since a serious marathon runner’s harder days are especially taxing.

But at the top level of the sport, everyone is doing “high mileage,” and almost no two runners train precisely alike. So, the allocation of those miles clearly matters.

Assume you have committed to a maximum of X miles a week in a marathon build-up. You could aim to simply split those X miles into as many 26-mile runs as possible. But most people training for marathons would have exhausted their miles after two runs, and I would guess that far fewer than ten percent would have room for three. So even in a runner who was game and durable enough to try this, it would quickly have a ceiling effect.

You could also split X into six or seven equal runs. If you’ve committed to 70 miles a week, then 10 or 11.5 miles per run and per day would probably get you to the finish line, but looking markedly less triumphant upon arrival than had you relied on a more varied plan. Obviously, a repeating weekly plan including, say, one 18- or a 20-miler at the expense of the other five or six runs would better serve your needs. But we* just established that a parade of marathon-length runs is a dead-end, too.

Clearly, we must regularly indulge in long and long-ish runs. But how many is too many?

The answer is three. A frequency of two runs of at least this length every seven days seems to work for a high percentage of runners when combined with one additional higher-intensity day (usually track-type repetitions less intense than they would be if the same runner were training for a track race or 10-mile road race).

Versatility of task execution

You can jog your recovery runs as slowly as you like. An important point I picked up from Pete is that a runner shouldn’t waste any longer efforts. If your job for the day is to run a pair of 8-milers, then go ahead and pitter-patter through all 16 miles. But if your task is a single 13-miler, than take advantage of the relatively rare excursion into 90-minute-and-above territory and don’t jog the whole run.

This led me to later come up with three basic ways to do a medium-long run: at around 80 percent of marathon pace, with four or more miles of threshold running included, or with the final 10 or 15 minutes used to gradually accelerate all the way to 5K race pace. The last of these is the KK.205.38.02 variant, an idea I adapted from the way Khalid Khannouchi, the American men’s marathon record-holder since April 2002, reportedly finished some of his long runs.

Additionally, a medium-long run doesn’t come at the expense of another weekly workout. It is never just a long jog, and it does all it can to fit seamlessly and non-controversially into existing systems. And as a possible bonus, runners who wind up having to skip a long run in a given week owing to bad weather or illness will at least have already logged a long-ish run that week if they’re MLR devotees.

Reliability of effect

If you run for 90 or more minutes, even if you’re practically crawling, you accrue a significant training stimulus. If you plan to run 4 miles easy, 4 miles at threshold, and 4 miles easy—all continuous—and discover it’s just not a great day for a tempo run, you can do one-minute on/one-minute off and both make the run count and distract yourself from the fact that you’re not feeling perfect.

Once a medium-long run is over, it will almost certainly produce a gain in fitness even if the pre-run plan disintegrates. If you set out to do a 4-mile tempo run with a 1-mile warmup and a 1-mile cooldown, and that falls apart, you’ve basically done an easy run with an emotionally unsatisfying surge.

Also, if you do 20 or 30 minutes of easy running and then gradually accelerate through marathon and 10-mile and 10K race-pace to 5K race pace over a one-and-a-half to two-mile stretch, this is exhilarating and clearly offers a training boost. But start this 75 minutes in off an already decent pace and it’s a different experience—one that subjectively has a lot in common with late-race marathon fatigue. If you do one of these and you can’t pick it up to the required pace without a supreme effort, but commit to finishing strong and picking up the pace somewhat, it still counts for a lot.

Social factors

You may have to work to find someone willing to accompany you on a Wednesday (usually, after a Sunday long run) jaunt of this length, assuming you like company anyway. It’s very helpful to have an experienced pace guide with you if you decide to start not only doing medium-long runs but making them count and infusing them with the kind of harder running you’re used to dedicating to shorter or stand-alone workouts.

The kinds of characters willing to spend midweek mornings doing things like structured medium-long runs tend to be especially colorful and supportive for some reason. So even if you despise people absolutely, find one or two who are fit, don’t make your gorge rise on sight, and are unlikely to detect the searing misanthropy that guides your evert decision and thought when not running for at least 90 minutes, but generally no longer 105 minutes and almost never longer than two hours. They may even make you smile, especially when you realize how easily you can snap into a quicker pace after being on your feet for a couple of hours thanks to all the bonhomie and sly physical abuse.