Why the NHL's basic ranking system sucks

If wins are wins and losses are losses, don't reward both

I will probably be making at-least-twice-monthly posts about oddities or trends I discover when scanning the standings and statistical leaderboards in the men’s sports considered the “big four” in North America: Basketball, baseball, football, and hockey. This has been a source of fascination for me since the advent of optional contests and the numbers used to assess performance in those games. The subject bores most people, but those who share my fascination usually tend to be all-in. So, I expect that most people will skip these posts outright, while about six hardy souls (always the same six) will read to the end and enjoy them immensely. Or at least be relieved I’m writing about an emotionally neutral subject. Too bad I won’t be able to keep an official score sheet.

When I was a young kid, there were 21 National Hockey League franchises, which were split into two conferences and four divisions, and played 80 regular-season games to whittle the playoff field all the way down to 16 teams. Today, those two conferences and four divisions include 32 teams, which play 82 regular-season games to determine the 16 that qualify for the postseason.

More critically—if that word can apply to sports at all, which is iffy—in the days of my young youth, regular-season games could end in a tie. If the score was even after three 20-minute periods, until the 1984-1985 season, that was it. Starting that season, in my rapidly aging youth, teams tied at the end of regulation would play a five-minute sudden-death overtime period, and if neither team scored, the game would end in a tie.

For standings purposes in those days, probably because ties were common, the NHL eschewed using winning percentage to rank teams, and instead awarded two points for a win, one for a tie, and none for a loss. This is a faithful simulacrum of winning percentage: In a W-L-T system (like that used by the National Football League), to compute that number, you scratch the ties and add half an additional win and half an additional loss for every tie a team has. For example, a team that goes 15-13-2 in a 30-game regular season has, for in-context purposes, gone 16-14 for a winning percentage of .533. (I realize that a decimal number is not a percentage, and that there really should be a leading zero before the decimal point. So do sports leagues, but this is a tradition as old as my fascination with the data they generate.)

The important facet of this is that in the old-school NHL, if winning percentage had been used (or at least displayed) instead of points, the standings would not have changed—it was impossible to have a lower number of points that a team with a lower winning percentage. That seems fair, right?

In 1999-2000, by which time I was nearly all grown up, the league decided to give teams that lost in overtime one point just for making it to overtime. Then, in 2005-2006, when I was (alas) no child anymore, the NHL decided to go to a “shootout” system, so that if the score remains tied at the end of one overtime period (in which now only three players per team can skate at once), a three-round shootout ensues. At the end of all of this, the winning team is awarded two points and the losing team one.

The superficial logic is obvious: Give teams who at least hang in there for 65 minutes more than those that succumb after a mere 60. Actually, it has nothing to do with that: The rule change was made during a season-long 2004-2005 lockout, and league officials decided they needed to do something to stimulate fan interest after a year of no NHL play.

The upshot is that points and winning percentage have become uncoupled, and this can have consequences when comparing two teams with greatly different tendencies to play games that reach overtime, lose in overtime, or both.

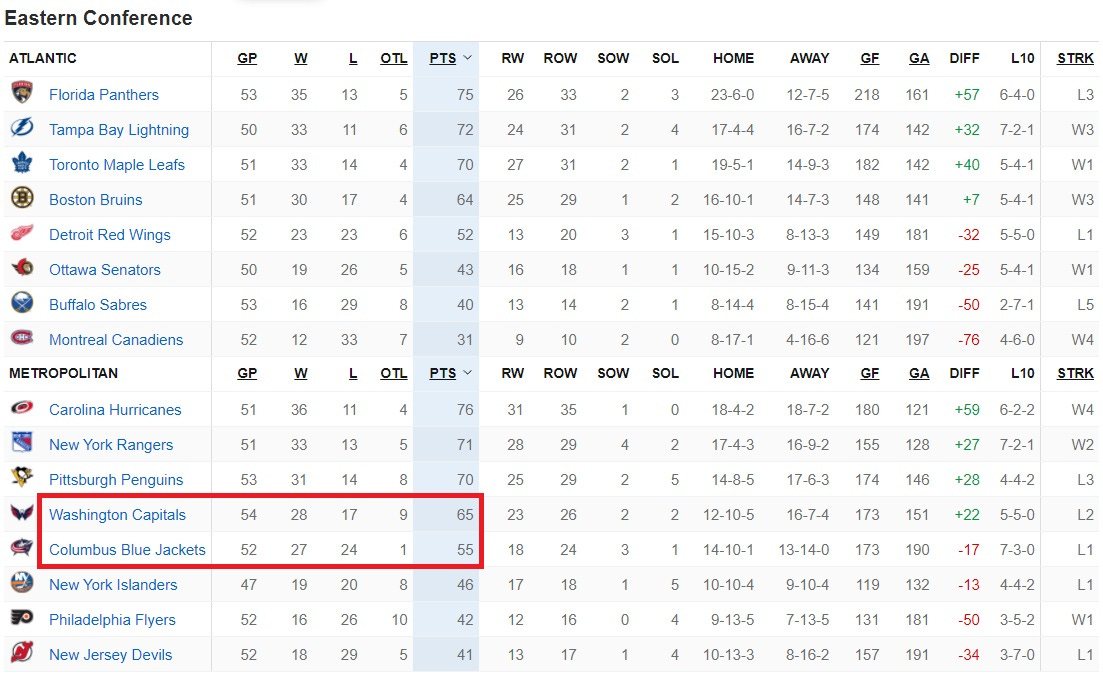

Below are the current standings in the NHL’s Eastern Conference, about two-thirds of the way into the regular season. The eight teams that make the playoffs in each conference include the top three in each division, along with whichever two excluded teams in either division have the most points.

If the regular season ended right now, the Columbus Blue Jackets, with 55 points, would be the best team to not qualify for the playoffs. The Washington Capitals, ranked seventh in the conference, are 10 points ahead of the Blue Jackets.

The Caps have played two more games than Columbus, but pretend Columbus just went 2-0 in a doubleheader, so that each team has played 54 games. Despite its burst of imaginary proficiency, Columbus would still only have 59 points. Washington must simply be the better team?

If so, it’s not by as much as the standings suggest. If you convert Washington’s 28-17-9 record to 28-26 (remember, that third column represents losses, not ties), the Caps are revealed to have a winning percentage of .5185. If you convert the Blue Jackets’ 27-24-1 mark to 27-25, that club’s winning percentage is .5192. If a win is a win and a loss is a loss, Columbus should be ranked ahead of Washington, and in every other league I can think of, it would be.

This could be consequential if and when the regular-season ends this spring. Washington has 28 games left and Columbus 30. Assume both teams manage to either avoid overtime games, win within five minutes when they don’t, or prevail in the shootout when they can’t do that, either. If Washington continues at its current level of play, it will win 15 of those 28 games, and finish the season 43-30-9 for a total of 95 points. For Columbus to get to 95 points, it will have to amass 40 more points in 30 games somehow, and one way to do it is to go 20-10. That would leave the Blue Jackets with a final record of 47-34-1.

Treating all losses as losses and looking at these “equal” teams’ winning percentages, the Blue Jackets’ 47-35 record would give them a mark of .573, while the 43-39 Capitals would come in at .524. You can see here that the difference is so great that Columbus could wind up several points behind Washington at season’s end despite a significantly better true winning percentage (might as well start calling it something, if ESPN hasn’t already) and miss the playoffs.

I’m sure that a cursory search would reveal numerous seasons—maybe even most of them—over the past fifteen years in which teams have been arguably screwed in the way Columbus stands to take a butt-reaming in 2021-22. The lesson is clear: When choosing a name for an expansion team in a professional sports league, don’t pick such a stupid one, even if that curse seemed not to affect the Las Vegas Golden Knights out of the gate.

(Social share photo of the Hanson brothers from the 1977 instant classic film “Slapshot” courtesy of Universal Pictures.)