A shallow dive into Katie Ledecky's profound dominance

Someone has presumably checked her for fins, flippers, a hidden intrarectal motor, etc.

When Will Thomas decided to bravely call himself Lia Thomas and switch from the University of Pennsylvania men’s swimming team to the women’s team for the 2021-22 NCAA season, the general ruckus this created, along with my complete ignorance of the sport of swimming, led me to discard a thought almost as quickly as it had registered: Competing as Will Thomas, this person was—despite being one of the better swimmers in the Ivy League—barely faster than Katie Ledecky, regarded as the best female swimmer of all time.

The reason this struck me as odd was knowing that a similarly decent Ivy League male runner is considerably better than the best women in the world. It’s not close. In the just-completed Division I NCAA indoor season—and I'll be reviewing the past weekend’s collegiate and high-school championships as soon as I can simmer my ass the fuck down—over fifty Ivy League men ran faster than Genzebe Dibaba’s indoor world record of 4:13.31 (which is at least a slight outlier compared to #2 Gudaf Tesgay’s fastest time of 4:16.16) and thirty Ivy Leaguers identifying as male bettered Dibaba’s 3,000-meter indoor world record of 8:16.60.

So how is it that any female swimmer is fast enough to keep up with a reasonably solid NCAA D-1 male? I had forgotten the issue until yesterday, when Ledecky, who will turn 26 on Friday, broke her own national record of 15:03.31 in the 1,650-yard freestyle with a time of 15:01.41.

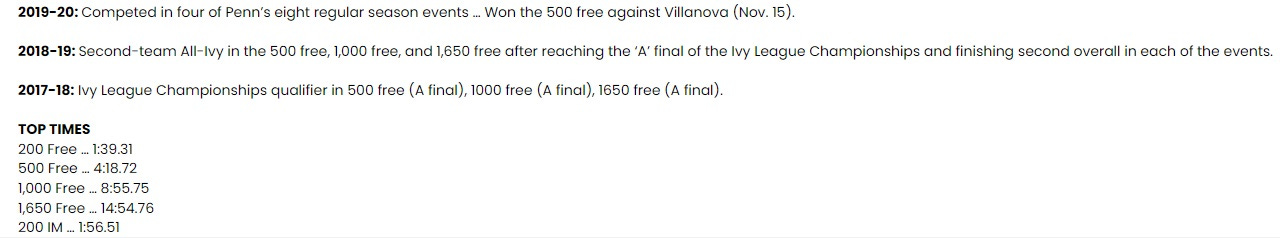

Here is Thomas’ swimming record as Will, per the U. Penn athletics Web site:

Across the freestyle events, Will Thomas’ times are only slightly better than Ledecky’s, which in the longer three of these events are national records. (I don’t think the rest of the world bothers with these archaic imperial-unit distances anymore, if they ever did.)

I went to this page and called up the all-time top fifteen performers in the 200-, 500-, 1,000-, and 1,650-yard freestyle events for both sexes. I accounted for the fact that Ledecky’s new 1,650-yard record hadn’t been added; maybe it’s there by now, especially if you’re looking at this in the year 2029.

Duration-wise, these are roughly equivalent to the 800 meters, the mile, the two-mile (or 3,000-meter steeplechase), and the 5,000 meters in athletics. So Ledecky being competitive in all of these swims, but vulnerable in the shortest, makes her swimming exploits roughly analogous to those of a runner like Sifan Hassan.

Actually, Sifan Hassan is the only runner “like Sifan Hassan.” And no one with such a profile would ever be viewed as free of performance-enhancing drugs by a sensible observer. When someone has great natural range, then doping just allows him or her take special competitive, and thus financial, advantage of his or her talent. Hassan—who’s now 30, ran poorly in 2022, and is probably fi-niiiiiii-to—could make a javelin test positive by merely handling the poor thing for a few seconds.

Ledecky is a marked outlier in the longest three of these distances. Her advantage over #2 all-time starts at just under a second per 100 yards of race distance and grows to well over a second per 100 yards—more like 1.5 seconds—in the 1,650 yards.

Notably, here are the gaps in seconds between Ledecky and #2 all-time, and between #2 and #15 all-time in those three events:

4.84, 4.17

11.12, 17.61

22.40, 16.36

In the 1,000 yards, all-time #2 Katie Anderson is herself an outlier, being over six and a half seconds faster than #3.

Meanwhile, on the men's side, the clustering between #1 and #15 is so close in the same three events that I didn't bother dividing it into two parts: 3.09, 12.41, and 15.25 seconds. Toss Katie Ledecky, and the bunching at the top of the sport of swimming isn’t notably more pronounced on the male side than it is on the women’s.

Here are the differences between the men's and women's #10 all-time performers in these same events, in percents:

4:08.75 vs. 4:32.66 = 10.96

8:44.11 vs.9:25.79 = 10.80

14:24.43 vs.15:36.27 = 10.83

Remarkably consistent. And very close to the gender performance gap in world-class running.

Here, in contrast, are how much slower Ledecky's national records are percentage-wise than the corresponding male records:

4:06.32 vs. 4:24.06 = 7.20

8:33.93 vs. 8:59.65 = 5.00

14:12.08 vs. 15:01.41 = 5.79

Nothing weird about that at all. Imagine a woman having run a sub-9:00 steeple when the WR was 8:33, which was in the late 1950s, when women and girls who avoided Catholic school were barely allowed to perform oral sex, much less run, jump, and otherwise have good, clean fun. Or a woman scaring fifteen minutes in the 5,000 meters at the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics, when the men's world record was 14:17.0.1

I have no reason to think female outliers this extreme "should" happen in swimming, but again, apart from math being math and knowing that fluid drag is an issue in the pool just like it is in running, I know nothing about swimming.

That said, I assume no one in swimming with a clue thinks Ledecky is anything but that sport's Allyson Felix or Sydney McLaughlin—that is, someone who can be considered a “made” athlete by the sport’s governing body marketing arm and will thus never test positive unless she or someone in her corner crosses the wrong executives or bureaucrats.

Women were not offered a 5,000-meter race at the Olympic Games until 1996. In 1984, 1988, and 1992, the “equivalent” was the 3,000 meters. Until the addition of the women's marathon in 1984, female runners did not compete over distances longer than 1,500 meters at the Olympic Games.

Despite these belated advancements, the International Olympic Committee probably remains among the most sexist organizations of its size, scope, and influence on the planet.