Colorado State Champs: Stutzman puts on a show, a nation-leading (sort of) 45.36, and a dramatic state record in the long relay

This might just be the best way to stage a high-school track and field state-championship meet, given the resources

The three-day 2023 Colorado State Track and Field Championships ended yesterday. I didn’t go down to Lakewood for any of the action, which unfolded in weather that was for the most part great for distance runners but uninviting for sitting around.

Complete results are here. The long-form highlights:

Emma Stutzman of Pomona High, one of a foursome of Colorado girls who broke ten minutes for 3,200 meters at the Arcadia Invitational last month, turned in perhaps the best distance triple (800m, 1,600m, 3,200m) in American high-school history despite losing the two-lap race. (One of the four, Isabel Allori of 3A Liberty Commons High School, missed the meet with an injury.)

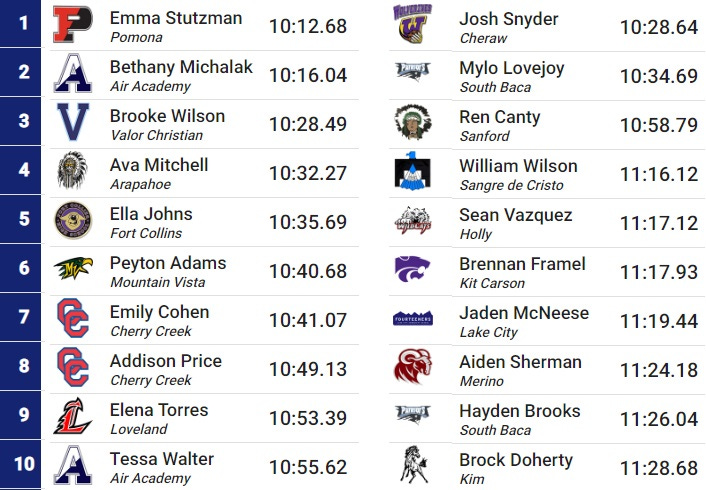

On Friday morning, in the 5A 3,200-meter race, U.S. #4 Stutzman (9:56.34 PR at Arcadia) outkicked Air Academy’s Bethany Michalak (#7, 9:57.86 PR) to win with ease, 10:12.68 to 10:16.04. U.S. #12 Brooke Wilson of Valor Christian (9:59.49 PR) was only three and a half seconds behind Stutzman and Michalak at the bell, but could only produce an 80-second last lap, which took Stutzman all of 67.82 seconds. Stutzman, in winning what was somehow only her first statewide track title, was well shy of breaking the state record Cherry Creek’s Riley Stewart (now at Stanford) set last spring (10:06.23).

Now for the frightening details. At an altitude of 5,550’, a 10:12.68 translates to about 9:54.8 at sea level. That’s impressive on its own, but Stutzman’s first and second halves were 5:17.19 and 4:55.49, and she ran her last 800 meters in 2:21.22. Those splits are sufficiently lopsided to reasonably speculate that Stutzman could have run under 10:00 at JeffCo Stadium this weekend with sufficient competition and maybe pacing lights.

On Friday afternoon, Stutzman returned to the track for the 800 meters. She led at the bell in 64.1, but was unable to hang thereafter with Rosie Mucharsky of Denver East and was beaten cleanly, 2:09.57 to 2:11.32. Boulder High’s Kiki Vaughn, the daughter of elite marathoner Sara Vaughn, was fourth in 2:13.10. All of these times are altitude-compromised by about one second.

On Saturday afternoon, Stutzman, Wilson, Michalak squared off for the final time in their Colorado prep careers, this time in the 1,600 meters. The pace seemed ambitious enough from the gun, and Michalak, the midrace leader, was a hair under 2:22 at 800 meters.

Then the pace picked up. At the bell, Stutzman was on the shoulder of Michalak, who split 1,200 meters in 3:32.39. But Stutzman essentially replicated what she’d done the previous morning in the 3,200 meters, covering her last lap in 67.49.

The result was a 4:39.94, laying unapologetic waste to Stewart’s 2022 state (4:44.13) and state-meet (4:45.96) records and dragging Michalak (4:42.65) well under the “old” mark.

In all, nine girls in the race broke five minutes despite this group conceding about 6.5 to 7 seconds to the high altitude. On the day, sixteen Colorado girls went under five minutes, with four doing so in the 4A race and three more doing it the Allori-less 3A race.

Stutzman’s time converts to about 4:33.11 at sea level, of a piece with Alexa Efraimson’s 2014 national record (4:33.26).

The enrollment cut-off for CHSAA 1A classification is 97 students, whereas all 5A schools have at least 1,368 students. This seemed a sufficient handicap to score the 1A boys’ and 5A girls’ distance races against each other, cross-country-style.

Both “meets” were blowouts. In the 1,600 meters, the girls “won” 24 to 35, with a breakdown of (1, 4, 5, 6, 8, [9, 10]) and (2, 3, 7, 11, 12).

The virtual 3,200-meter matchup was a 17-43 bloodbath, again in favor of the girls: (1, 2, 3, 5, 7 [8, 9]) vs. (4, 6, 10, 11, 12).

Nevertheless, in the boys’ 1A 800 meters, the top nine boys had better times than Mucharsky’s 5A-winning 2:09.57. Any Theories about the gradual, then sudden and complete loss of dominance with decreasing race distance observed here?

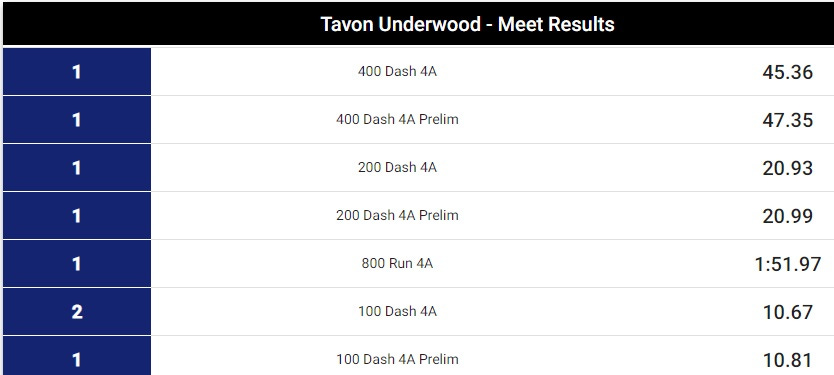

In the 4A 400 meters, Mead High’s Tavon Underwood shocked everyone on hand by running a 45.36. Underwood, who went into the day ranked #16 in the country with a 46.60 run at the Arcadia Invitational, knocked 1.24 seconds off that time to establish a new state record, shattering the 2006 mark of 46.23 by J. T. Scheuerman of Littleton High.

Underwood’s time is faster than the listed U.S. #1 mark of 45.46 recorded by Sidi Njie of Westlake, Georgia last weekend. But because races at high altitude that last less than about 100 seconds actually receive a slight performance boost, that 45.36 is worth closer to a 45.74 at sea level. Still a decent gallop, all things considered.

Oh, Underwood kept busy during the rest of the meet, too. I’ve never heard of anyone running the 100-meter dash, 200-meter dash, 400-meter dash, and 800-meter run at the same meet, much less trying to win state championships in all four events. I mean, it’s difficult to find a really fast sprinter even willing to try the two-lap event. But Underwood, who’s off to Kansas State University in the fall, nearly won all four races, his only blemish being a second-place finish in the shortest of them.

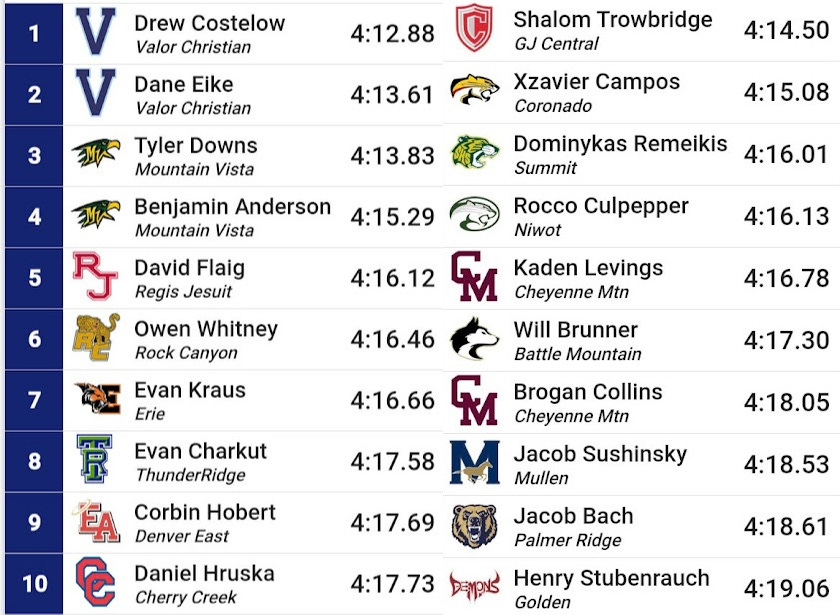

The 5A boys’ 3,200-meter relay also produced a state record. Mountain Vista closely trailed Cherokee Trail heading into the final handoff, but Cherokee Trail botched that handoff, resulting in a dropped baton. Vista anchor Tyler Downs, who, split 1:52.14 to carry his team to a 7:42.58, a U.S. #4 time and well under the state record of 7:45.10 set in 2001 by Smoky Hill. Despite its sins, Cherokee Trail just missed the old record, its 7:45.69 now standing as the nation’s #11 time.

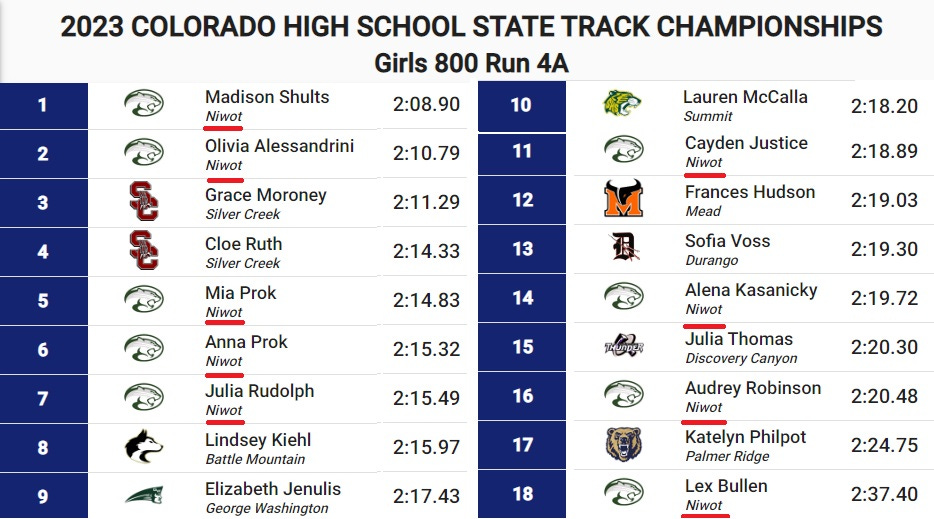

The Niwot High girls, although a 4A school, have a stronger contingent of half-milers than should be possible at the high-school level. Such is the natural result of a cohort of phenoms fed through a self-reinforcing juggernaut-generator, other than there being nothing “natural” about this process or tradition.

From these results, one gleans that Niwot could field a 3,200-meter-relay “A” team capable of 8:49 or so, and a “B” team capable of 9:13-ish. Madison Shults, however, ran 2:04.28 earlier in the season at—get this—the Arcadia Invitational. Although Niwot cruised to an east win in the 4A 3,200-meter relay on Thursday morning in 9:22.60, there is no reason the team can’t threaten the U.S. #1 mark, 8:44.98, held by Union Catholic of New Jersey. I assume the idea is to win a national title in this event at one of two national-championship meets in mid-June, either the adidas version in Greensboro, North Carolina or the New Balance version in Philadelphia.

Speaking of Niwot, not only does it have a freshman girl whose dad is a former Olympian, it has a freshman boy with two former Olympians as parents. Addison Ritzenhein (Dathan’s daughter) won the 3,200 meters in 10:30.05 and then was third in the 1,600 meters in 4:58.04. Rocco Culpepper, the son of Shayne and Alan, was fourth in the 1,600 meters in 4:16.13. You don’t see a lot of ninth-grade kids sniffing a 4:10 sea-level mile.

The results of the boys’ 5A and 4A 1,600-meter races are interesting in that they seem to reflect the slight differences in capital expected as a result of slight differences in enrollment. The 5A runners had better times at each top-ten finishing positions than the 4A crew, but the difference was no greater than 2.18 seconds for any place and was as small as 0.66 seconds.

This kind of pattern only reliably emerges when races are not overly “tactical.” In other words, when the kids bring it. Which, despite the 1,600 meters being at the end of a long meet, and many kids tripling, these athletes clearly did.

What follows are not further observations about the 2023 championships, but general comments on the competitive dynamics of the meet and the obviously healthy state of the sport in Colorado.

It’s a lot easier to double or triple as a distance runner when the races are spread across multiple days, at least from a physical standpoint. Whether this is true from a mental standpoint is less clear and depends heavily on the psychology of individual athletes. Some of these kids had been sleeping in hotel beds for three nights when they hit the track on Saturday for their third (or fourth, if a relay-team member) events. Some of them, even the hardcores, were probably weary of the entire production by the time it was halfway over no matter how well it was going.

Still, while multi-day high-school track-and-field championships are staged in only a handful of U.S. states, this is the norm at the collegiate and professional levels. Although it’s literally very costly, it really gives the kids the best chance to succeed in the events they’ve prepared for, and gives the ones moving on to collegiate competition (such as the entire Niwot girls’ team) a taste of what to expect.

It is presumably easier to pour high-school capital into outdoor track as a sport when it has no winter counterpart to eat into that capital. The CHSAA conducts no official high-school indoor track season, and although this sounds dumb if all your knowledge of Colorado is limited to the Fort Collins-Denver-Colorado Springs corridor and the ski towns, the state just isn’t wintry enough to justify prep-level indoor track. And if there were an indoor season, the only indoor races for kids who live off in the state’s forgotten corners, where there are no indoor facilities within two or more hours, would be at the state meet itself—a novelty, but not an ideal competitive set-up.

At the same time, there is no shortage of open meets in Colorado available for kids who want to spice up their winter training and stay sharp between cross-country and outdoor track. Athletes can take a break of sorts over the winter and modulate the degree to which they back off from competing.

Finally, the people who create the state-championship schedule have done a masterful job of spreading out the distance races, relays, and sprints in a way that allows kids to undertake predictable track and field-event doubles and triples. Given that they have to do this for five classifications, and knowing the kinds of people you find involved with prep track and field, I suspect that a bunch of math teachers came up with the general scheme years ago, and—now that they’re all quite old—stand collectively averse to the easy computerization of this task that’s possible now. Math teachers have kept high-school track alive in every state I’ve ever lived in.

I’ve lived in Colorado for a long time now, at least by my once-itinerant standards, and probably won’t be convinced to leave it. Even as a recreational runner, it’s very easy to see how the place breeds the kind of aerobic panache it does. A lot of the dynastic high-school programs around here are in affluent communities, but that’s only a part of the deal. You will also find some incredibly wise, organized coaches in this area, people who couldn’t stop obsessing over the task of turning kids into happier, faster little citizens if they tried.

The place really does something to you, and this is as true in Grand Junction, Cortez, Alamosa, Fort Collins, and Manitou Springs as it is in Boulder and its bevy of satellite L-towns. It’s great to see whatever this is happening to so many young people, whether or not they can precociously appreciate both the ineffable and the tangible delights at their disposal.