The Colorado State Championships are almost here

Putting the state's historically fast contingent of 3,200-meter girls into perspective

The 2023 CSHAA State Outdoor Track and Field Championships will take place Thursday, Friday, and Saturday at JeffCo Stadium in Lakewood, situated at an elevation of 5,551’ just west of Denver. At least they’re scheduled to happen over those three days. Two of the past four of these gatherings (those in 2018 and 2022) were scuttled by snow, forcing a reorganization of the four-classification 2A, 3A, 4A, and 5A) mass championship on the fly. (Thanks almost solely to Tony Fauci, there was no 2020 state meet in Colorado.)

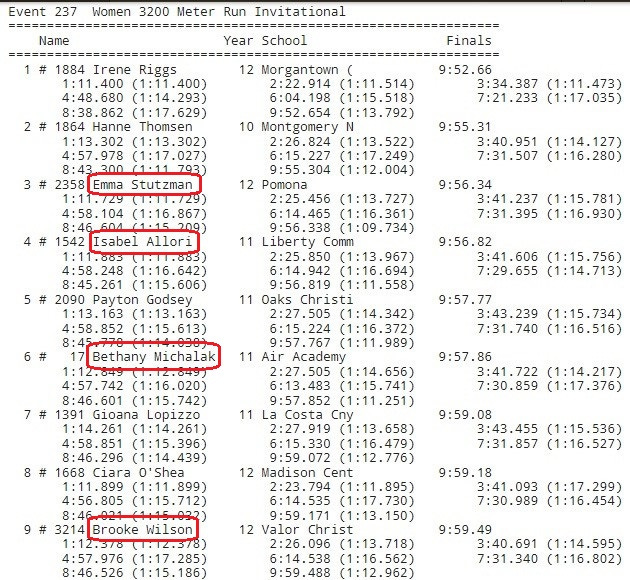

Colorado always brings distance talent disproportionate to its six million residents to this meet. This year, the biggest story is four girls from Colorado having broken 10:00 for 3,200 meters this season. As I wrote a month ago, all four did it in the same race, at the Arcadia Invitational, when a total of nine girls went under the barrier.

According to Milesplit’s database, 39 girls have broken 10:00 for 3,200 meters since the event was adopted almost universally by American high schools in 1981.1 Counting performances in the two-mile faster than 10:03.2 or so, 50 have done so.

It is no surprise that over 40 percent of these performances have been recorded in the “superspikes” era that for high-schoolers commenced in around 2020, certainly by 2021. It remains unclear how much the average runner in a given ability range gains compared to old-school footwear, but it almost can’t be more than a second a lap at four-minute mile pace, which would represent a gain of 1.7 percent. Yes, the sport has been revolutionized, because anything that helps really fast runners even a tiny bit is critical. But a girl who runs 9:52 to 9:59 is in the same class of runner who was capable of 10:00 in 1980s track spikes. All of whom were boys, including me.

In my junior and senior year of outdoor track, I qualified for the New Hampshire Division I State Meet in the 3,200 meters by running under 10:10 during the regular season. Both times, I advanced to the following week’s New Hampshire Meet of Champions by placing in the top five. And in both years, I advanced to the New England Championships by placing in the top six at the Meet of Champions.

In 1987, my junior year, I wound up second at the State Meet on a 95-degree day merely by not running like a complete jackass. A kid from Nashua, talented but often mindless, went out in 66 seconds and dragged almost everyone with him. I went through 400 meters in 72, 1,600 meters in 5:02, and just kept reeling in sun-scorched zombies until only Jon Lacombe of Memorial, easily the best in the state, was in front of me. My time was 10:04, only three seconds slower than my best. I think I went in seeded eighth or ninth.

The next week at the Meet of Champions, the weather was favorable, and along with many others I showed up in Keene having just taken the SAT. The field again went out very fast, with me in last place after one lap despite running it in 68 seconds. I wound up third in 9:50.1, with three kids pretty close behind. I think the last New Englands spot went to that kid from Nashua, who ran 9:55, and I think he was the last finisher under 10:00.

In 1988, my senior year, the weather for the D-1 State Meet was exactly the same as the previous year’s—blazing hot and steamy. Maybe even worse. This time, the field went out wisely, hitting 2:31 at two laps. Then someone made a move and I didn’t go with it, morosely content to swim my way to a sterling 10:20 for fourth place. The winning time was 10:01.

At the Meet of Champions the next week at Spaulding High School, the field once again went out in 66, and I once again “sat back” with a 68. I wound up an uninspired fifth in 9:49.9, over six seconds off my best.

At the New Englands at Boston College the next week, on an oversized track in sweltering heat, I ran 9:43 or 9:44 out of the slow section without hearing a single split the entire way.

Consider what any of these races might have looked like had they included Emma Stutzman, Isabel Allori, Bethany Michalak, or Brooke Wilson. Not only would they have had the jets to mix it up with at least half the field, but they would have run smarter than everyone else and made up differences in fitness on the rest of us.

New Hampshire is a small state, and this was all thirty-five or more years ago. Nevertheless, this seems like an astonishing level of gain by female high-school runners.

The boys I ran with and against were acutely aware of what female runners could do. In the spring of 1984—thirty-nine years ago this weekend, in fact—Cathy Schiro placed ninth in the first U.S. Olympic Team Trials for women, held in Los Angeles. I became a runner about five months later and quickly learned who Cathy Schiro was. The general consensus among the older boys in New Hampshire was that of the dozen or so Granite State dudes who could beat Schiro’s cross-country times, none could have turned in a 2:34 marathon.

Because the Colorado State Championships span three days, most top distance runners double or triple in individual events, with many of them also running a 4 × 800-meter relay leg. I would guess that all four sub-10:00 girls are running the 3,200 meters at States, but if so, there will only been one match-up between any of them. Allori runs for 3A Liberty Commons High in Fort Collins, Michalak competes for 4A Air Academy in Colorado Springs, and Wilson (Valor Christian High of Highlands Ranch) and Stutzman (Pomona High of Arvada) are 5A competitors.

The times won’t be fast—a 9:52 in the Sacramento area is worth around 10:10 at JeffCo Stadium—but the racing should be a treat. Coaches have a special challenge in preparing for a multi-day championship meet, which most states do not feature. The temptation to overwork everyone has to be balanced against the unusual opportunity to take advantage of the protracted event schedule.

When today’s running “journalists” talk about gains being made in the sport by girls and women, or present another of their supposed “reckonings” or “paradigm shifts” meant to establish that there is something different and powerful about today’s class of elite distaff perambulators, they focus on externalities that allegedly have bearing on this potency without describing how. That runners are “newly” willing to Take Up Space despite a greater mass of melanin or adipose, or dye their hair to match the color of The Incredible Hulk’s skin, does little to explain why so many of these girls are so damned good. They could at least stand there and shout “Holy shit!” if they lack the background to fully appreciate what they’re seeing.

And until a few years ago, concerning teenage female prodigies, the party line among “feminist” pundits like Alison Wade—none of whom seem to comprehend why the example of Mary Cain’s career flameout is not generalizable—was “too much, too soon.” Maybe they were thinking also of the sad case of Schiro, who as Cathy O’Brien went on to make two Olympic teams in the marathon and set a world record for 10 miles in 51:47.

This class of observers, true to form, has taken up cheering on the feats of these prodigies along with the rest of us*, all without revealing what led to their philosophical shift. Obviously, they realized they could get more attention and clicks by expressing appreciation for unusually great performances athletes in the sport of running, which they purport to admire and support.

Maybe too many of these folkettes are listening to girlboss Lauren Fleshman’s ceaseless barking about the sport not being built for girls to notice that she’s as misguided about this thesis as she is about all of her self-serving, incoherent ideas. When you look at what young runners are actually doing on the ground and how much they’re enjoying the ride rather than focus on what might be wrong or dangerous about their feats, you find yourself with a new view, because you see a sport rather than substrate for a culture war or a psychodrama revolving around your own shortcomings or flattened or elapsed dreams.

This meet invariably leads me to think of my friend Rich Martinez, who died in 2019. Richie held the state record in the 1,600 meters for an incredible forty years, running 4:10.98 for Widefield High School at the 1981 Colorado State Championships in Pueblo.

Unless a twister wipes out the entire meet, I’ll probably remember to return to all of this in about five or six days. And I will probably be at portions of it if I have the time, which I still have plenty of, but less than I did a few weeks ago.

With most U.S. tracks being built or renovated as 400-meter rather than 440-yard circuits—the difference is about 2.3 meters, with the metric distance being shorter—the 1,600 meters and 3,200 meters represented a compromise between the classic international distances (1,500 meters and 3,000 meters) and the traditional imperial mile and two-mile races.