Embracing their own incompetence, running's "journalists" continue pushing Nike's false Shelby Houlihan narrative

The usual attention-hounds demonstrate anew that they lack the insight, the ethics, and most of all the courage required for the job

On the evening of Monday, June 14, after being invited to a Zoom propaganda session hosted by representatives of the Nike Bowerman Track Club and framed as a press event, the nominal running journalists in attendance rushed to post their stories, almost all of which did the BTC and Shelby Houlihan—revealed in the Zoom session to have been serving a four-year doping ban since January 14—even more of a reputation-preserving service than the most optimistic onlookers on the Nike side could have hoped for.

Almost all of these “hot take” articles were dark comedies of unforced errors—Letsrun’s was an exception—although with distance running being a fundamentally comedic enterprise anyway, introducing the word “dark” in the absence of a real tragedy seems over-the-top. In this instance, the most dire outcomes were someone who’d shown all the hallmarks of doping being banned for using an old, oft-used performance-enhancing drug; her legal team coming up with a creative and well-timed firehose of misdirection and confusion in response; and a historically pliant, biased and incompetent running media, as if seeing its own existing pile of mistakes as one more personal best to surpass, yelling “Hold our beer!” and providing the public with a wealth of misinformation that any writer with a proper sense of shame would already be deeply regretting.

Not surprisingly, rather than admit they’d been rooked and correct their courses, the usual actors have either ignored or doubled down on their previous takes, knowing as always that as long as they all disseminate the same false or incomplete narratives, their positions in the feeble hierarchy of running-related media coverage are secure. In addition, outlets in the broader media—relying largely on the first wave of misleading stories from those same actors—have crafted a series of equally laughable articles of their own (I won’t have space to get to these today).

The story of Houlihan’s ban itself was still being steered by the BTC throughout last week, with the details founded on the illusory yet persistent idea that Houlihan was just starting her fight to preserve her athletic freedom. Houlihan also made the poor decision to take to the airwaves—not because she chose Fox News as a venue, but because she looked extraordinarily guilty—while her club-mates continued to supply sincere yet somehow slapstick social-media defenses of their wronged and suffering friend.

On Thursday, June 17, Houlihan’s name appeared on the Olympic Trials entry lists for the 1,500 meters and 5,000 meters, with first heat of the former event scheduled for the following day. This was never going to fly for a variety of reasons, and Houlihan et al. knew it. The U.S. Olympic Committee has ultimate control of the Trials, not USA Track and Field, the sport’s national governing body as well as a de facto operating arm of Nike led by an assortment of greedheads at least as inept as the average 2021 running journalist.

All this stunt accomplished was establishing something on the record for Houlihan supporters to later refer to as indicative of a still-uncertain outcome, months into her ban, as in: “If she was even temporarily put on the entry lists, there must have been a good reason for it.” There wasn’t, unless you consider the whole BTC charade of falsehoods a good thing. This was just another nonsense ploy, underwritten by the complicit dolts within USATF. But the usual useful idiots handled this just as they had initial round of misinformation, faithfully pretending that Houlihan was only banned in spirit and that the whole unfair set of spectral accusations against her would be rescinded in due time.

Before reviewing the latest stories about the Houlihan ban, to better illustrate just how off-key and out-of-synch this dilapidated media orchestra has sounded, I’ll describe the basic timeline of the ban and flesh this out with details most readers—perhaps envisioning a doping ban as procedurally similar to a criminal court case—may not know.

When an athlete’s “A” and “B” urine samples are both found have an over-the-allowed-limit of a banned substance, this immediately triggers a ban—that’s short for “banishment”—from the sport. This is because doping is a strict liability offense; if a substance is found in your body, you’re responsible for its presence there. This is markedly different from an everyday citizen being arrested and charged with something like cocaine possession or driving under the influence; even when those cases seem incontrovertibly destined to end in a conviction, a plea or a trial process always results before the accused can be considered officially guilty and subjected to all applicable penalties for the offense.

When Houlihan was informed in January that the urine sample she’d submitted a month earlier had tested positive for illicit levels of nandrolone metabolites, she was, just like anyone else in her situation, concurrently informed that she was now serving a ban. Think of this as the police coming to your house with a judge and a panel of jurists, finding a kilo of cocaine inside, and the whole assembly informing you that you’re now a convicted felon about to serve a three-year house-arrest sentence, starting that second, with the option to appeal the conviction and have the sentence reduced or expunged altogether.

Houlihan was banned for four years, the standard penalty for a first offense. Other athletes have served lesser sentences for first offenses, or had the positive result tossed from the punitive record outright, because they’ve been able to prove that mitigating circumstances (e.g., a diabolical masseur, tainted beef from Mexico, or “authentic” Mexican pork form Oregon) really did contribute to the presence of the substance in the athlete’s body. This is not a good sign for those expecting the full details of the Houlihan case, which may not emerge for months, to somehow reveal information suggestive of Houlihan’s innocence; rather, it should prime observers to expect something between a bland-but-decisive “Could not support fairy-tale excuse” and a bloodbath of embarrassing smackdowns.

In any event, the BTC, or its parent company Nike, somehow negotiated an agreement with the Athletics Integrity Unit to keep news of the doping ban hushed. This was apparently contingent on Houlihan’s inevitable appeal being heard in time for her to compete in the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials, which are now about halfway complete. Whatever the case, when Houlihan learned on June 11 that her appeal had been rejected, she was officially out of the Olympic Trials—probably not a surprise to her and her team—but also facing the fact that the AIS would now be releasing news of Houlihan’s ban to the public. This inspired the Zoom event and the various fables within that led to the initial round of bad coverage.

So here we* are. If you’re a regular reader, you’re bound to find gaps in the list below, as this saga has spread beyond the ordinary reach of track-and-field-related dramas and inspired a lot of sports-ignorant and biased, but self-important, blue-checkmark Twitter types to add their drive-by two cents. I’m trying to focus on stories by those for whom writing about running, however erratically, is either a profession, a source of regular freelance income, or a permanent hobby, to the extent these can even be distinguished from one another.

Last time, I pointed out the blatantly incorrect headline in Chris Chavez’s June 14 Sports Illustrated story. He or someone at SI changed this—silently—sometime in the 24 hours after it was posted, but well after the brunt of its initial impact could be curbed. (I noted this in an update to my post, but those who only read the e-mailed newsletter would have missed this. The world still turns.)

Please consider the monumental difference between asserting something as fact and reporting that someone has made an unsupported claim. In the absence of a detailed apology and explanation, Chris Chavez should never again be trusted to accurately report a story. But like the others in this motley assortment of information-hijackers, he won’t feel pressure to become more ethical until things like this start affecting his subscriber numbers and overall platform. That in turn won’t happen, because practically no one who claims to be a runner these days is discerning enough to care.

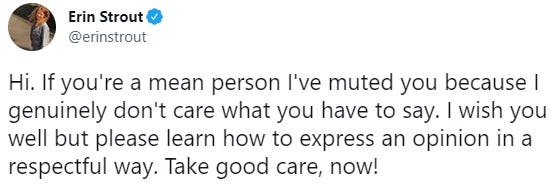

But would you want to be on the “bad” end of a guy like Chavez writing a supposedly objective story about you or someone in your family, given his proven ethics?Erin Strout’s June 14 story, which I already reviewed, was probably the most biased of the initial bunch. Since then, she’s continued to reveal why she, too, stands zero chance of developing into a legitimate journalist. For one thing, she literally doesn’t listen to her critics:

Strout doesn’t care what anyone has to say no matter how they say it unless it’s glowing, gushing praise. If she had any writing ability, she’d be an ideal PR hack. Instead, she’s just a hack.

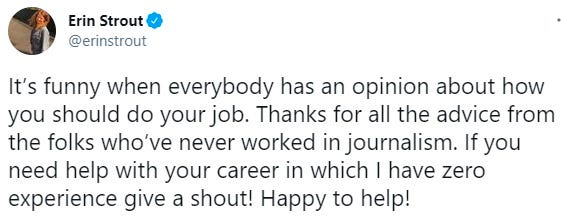

Worse than this, she has the audacity, or maybe just the legitimate cluelessness, to complain that non-journalists don’t know what it’s like to take heat for doing a tough job:The grim hilarity is that Strout, as always, took the coward’s way out of the real story, leaving her safe from ill judgments from BTC members who probably don’t read her dullness-streams anyway, yet is grousing here about her determination and courage going unappreciated.

Had Strout published a more skeptical story and put some hard but obvious questions out there, and gotten crap from any pro runners for it, people would be sympathetic to her complaints about how hard she has it. They would, in fact, be congratulating her on her courage. That feels better than a few hundred Twitter likes from faceless yahoos, but sadly, I don’t think it’s a feeling Erin Strout will ever enjoy.

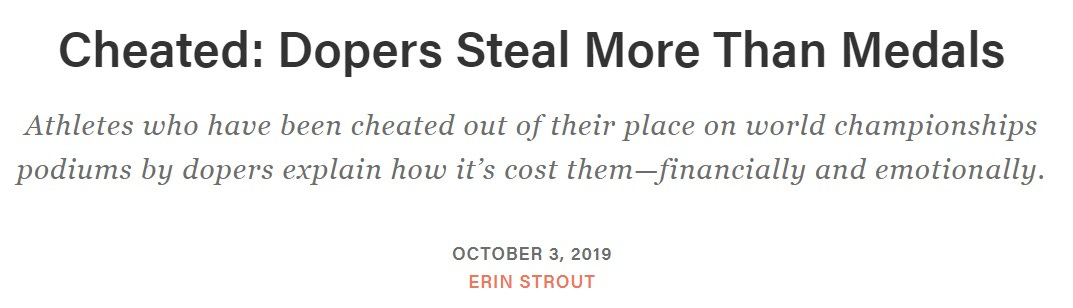

Perhaps she should refer to some of her own past work for inspiration:Letsrun’s Jon Gault wrote a story on June 15 presenting the ban in dichotomous terms from a fan standpoint. Titled “Shelby Houlihan’s Suspension Is a Track & Field Tragedy,” it outlines two scenarios: Houlihan is a standard doper and a villain, or Shelby Houlihan was screwed by a corrupt testing lab. Gault says he chooses to believe that she’s innocent.

I think that Gault wrote the piece as a kind of exploratory fiction or creative nonfiction piece, in the manner of a talented writer asked to vehemently defend an opinion he actually doesn’t believe. In other words, I don’t reject the piece—it’s got a lot of good information—so much as the situational intellectual honesty of its creator. Perhaps Gault really was moved by the words of Houlihan and Jerry Schumacher to genuinely land where he does in this essay. But I watched the same videos he did, and where Gault says he sees the emotional devastation of injustice on the faces of the BTC gang, I see instead desolation and anger bred of incurring serious consequences as a result of poor but understandable choices.

Anyway, fun read, but I don’t buy that a single saboteur could have gotten Houlihan unfairly suspended. I’m sure banned athletes have tried this excuse many times, and I would be shocked if a single person can ever sign off on something resulting in a four-year ban, without other verifiable links in the chain of evidence.Alison Wade didn’t have a chance to mention the Houlihan ban in her June 14 Fast Women newsletter, which was released on the morning of the Zoom event. But as I noted, on social media, she too took a sympathetic stance, one she for some reason thinks isn’t obvious. This captures it all:

When someone has been banned and lost an appeal of that ban, the only conclusion to jump to and the only factors to consider are that she was banned for a good reason. This is just another dumb and desperate attempt to muddy the waters. Remember, even these same “Let’s withhold judgment” types admit that Houlihan’s story is full of holes in places, albeit only because they have to.

Not content with pretending to sit on the fence on Twitter, Wade cranked out an “emergency” newsletter on June 18. She shows that she hasn’t accepted reality by observing that maybe, just maybe, the fact that Houlihan claims to have ordered one kind of burrito but eaten another is important. Actually, it’s not—to Wade or me or anyone else. It was important, months ago, when Houlihan was banned.

Wade, like most other American observers, is still trying to litigate a case that experts have already evaluated and closed. She’s thinking, “Maybe there’s something to this.” Anyone stuck in this phase is in frank denial. The case is not going to be tried and the outcome reversed in the court of confused and biased U.S. public opinion. Wade also complains—and this one really was good for an LOL—that people are assuming they know what she thinks without her having even given an opinion. Well, one, yes she has, and two, what the hell is the point of writing and disseminating a fraught newsletter while refusing to take responsibility for your own stances?

Wade was nonplussed by Houlihan appearing on Fox News to plead her innocence. Apart from obviously being unaware that she and the running media are doing at least as bad a job with the truth as Fox News ever did, this one’s easy. The numerically vast audience of that network despises globalist organizations, be it the UN, WHO, or one most people have never heard of like WADA. If anyone is willing to hear a tale of persecution from a pretty white girl from Iowa, it’s Fox News viewers. Moreover, that Wade is being particular about where Houlihan trumpets her supposed innocence shows just how much Wade really believes in that innocence deep down. And she shouldn’t believe in it: Houlihan looks guilty as hell in the segment. Her lawyer doesn’t, because he’s a trained smoke-machine who lies for a comfortable living.

Wade has cultivated a following of incessant victims who accept her baseline premise that women like them—mostly white and affluent—are getting the shaft in any situation in which one of their ranks is being punished for something. That’s fine; everyone should try their hand at a leadership position in life for a spell. But if she’d show some backbone, even in being wrong, it might make the blinders sewn over her eyes less opaque.

And I keep coming back to this amazingly well-timed—or if you’re Wade, ill-timed—observation from one week before the Houlihan ban was publicized:Wade doesn’t have to lose faith if she simply dismisses the validity of a ban because the athlete is American or teary-eyed over it.

Women’s Running didn’t want Strout to have all the story-mangling for herself, so Richard A. Lovett turned out a piece on June 17 slapped with the headline “Is Nandrolone Found in Pork? All Your Shelby Houlihan Burrito Questions, Answered.”

Lovett—who has been writing outstanding training-related pieces for various outlets for a long time, by the way—gives away the pointlessness of this pro-Houlihan display early on:

“At this point, experts for the most part, are reluctant to weigh in. But there is a plethora of scientific literature on the subject (much dating all the way back to the 1970s), and a few experts who were willing to talk off the record.”

Let’s see: Experts unwilling to use their names and a guy doing some digging through the literature versus the fact that Houlihan is serving a four-year ban for a reason.

Try, just try, to imagine a U.S.-based publication going to this much trouble to defend a Moroccan doper, with or without the implausible career arc and even more implausible (but “authentic American”) excuse, and the chorus of jeers that would erupt in the unlikely event this happened.

All of this is clickbait trash.Martin Fritz Huber threw his dunce-cap into the ring on June 15 with a story topped by a headline describing the Houlihan verdict as uncertain, helpfully dispensing of the need to scan the article below for signs of objectivity. Outside also can’t decide whether this uncertainty is “brutal” or merely “devastating.”

At one point in his unfurling of characteristic tedium, Huber observes:

It’s difficult to watch the press conference, which was put on by the Nike-sponsored Bowerman Track Club, and not come away with a sense that Houlihan is indeed an innocent victim.

I’ll essentially repeat what I said about Gault’s interpretation of the presser: Only someone psycho-emotionally primed to weigh the BTC garbage-dump as a wrenching revelation of impropriety by anti-doping authorities could possibly view it as such. Moreover, if you’re weighing what you already know about the case against a bunch of “I’m innocent” crying we’ve* all seen in some form by noteworthy dopers of yore, then you get points for empathy but demerits for credulity.

This post is near the e-mail length limit, so I’ll have to save my review of a few examples of excellent reporting on the Houlihan case (especially this gem), some Twitter nonsense, and my subjective summary of both the good and bad stuff for next time. Sneak preview: These people are truly hopeless, but I shouldn’t let what they say and do irritate me so much, especially dumbass Americans; and despite my nitpicky, negative-Nancy ways, I’m bursting with positive suggestions about how the media could have done this so, so much better, along with a broad explanation of why they didn’t and can’t be expected to anymore.