Flashback 35 years: An unplanned 23 in falling snow

Stubbornness and a questionable allocation of personal resources tend to manifest early in life

New Hampshire did not feature an official high-school indoor track season this winter. In the interest of keeping kids’ lives moving smoothly and their goals in progress, the state’s track powers organized a substitute state championship of sorts on Monday at the Hampshire Dome in Milford, which features a four-cornered track that, for the “Dome Championship,” seems to have been rigged using cones to be about 311 meters per circuit. NewHampshireTrackAndField.com’s recap is here, the results are there, and the video stream is everywhere.

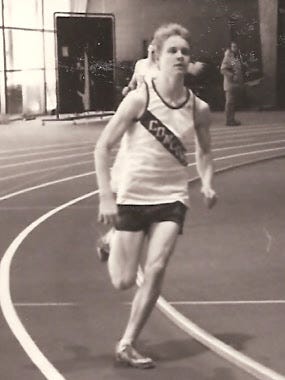

I competed at the NHIAA Indoor Track and Field Championships twice. In 1987, my junior year, the championships were at the University of New Hampshire, then in its last year of boasting a 160-meter (or 176-yard) track surrounding a dirt infield. Puddles would sometimes form on this officially sanctioned practical joke of a D-1 college track, with the source of the water an ongoing years-long mystery. Anyone who brought a light-colored handkerchief to breathe through during meets would only feel worse afterward, because the grime collecting on these clothes safeguards was only graphic, sooty evidence of what everyone was breathing during their races.

My race was the longest, the 3,000 meters. At a midseason league meet, I had run 9:32.6 on this crumbling eyesore, chasing Portsmouth’s talented but always-injured Daren Sanborn for almost nineteen laps. The Portsmouth coach was of great help to me in this race, because he kept bellowing “GET RID OF HIM!” at Sanborn whenever the two of us clopped into view every thirty seconds, and it occurred to me each time that the coach, who looked about eighty, should have known that this outcome wasn’t entirely in Sanborn’s control. But he did beat me.

That time was good enough to get me seeded sixth for the state championship race. But two weeks before States—and in those days there were no divisions needed, as only about twenty schools statewide even bothered sponsoring indoor track—I ran my last regular-season race, and it was a dud. I was chasing my friend Tim O’Brien of Pinkerton in another 3,000 meters, and O’Brien pulled away to a 9:26 personal best while I faded in the second half to a 9:38.

But before I could face Sanborn, O’Brien, and the other three fellows seeded ahead of me on championship night, I had two weeks to stew over closing the regular season so feebly, and to find in that stewing a means of exacting revenge on myself in a way that I could defend in my busy adolescent mind as productive.

That dud of a 3K was on the evening of Saturday, January 17, 1987. The next day, I decided I would do a long run, at least ten miles. I’m pretty sure the longest single run I’d ever done at the time was 12 miles, my summertime Bog Road/Riverhill loop. I had ideas of exceeding that distance so I could call the weekend something of a win. After all, States were still two weeks off.

It started snowing just before I left the house at around 1 p.m. I knew it wouldn’t be letting up, and that I’d be out there for a while. It was also cold—I would have guessed around 25 degrees, but as the temperature in the area that day ranged between 0 and 22 degrees (see January 18), I would have guessed optimistically. I wore a red Gore-Tex top-and-pants combo, and probably my 1985 Salem Screen Five-Miler long-sleeved T-shirt underneath. I know for a fact that I wore ski goggles, as well as a hat with a huge, floppy-ass pom-pom on it. I only wore that hat because every hat in our family closet boasted a floppy pom-pom of some caliber, and I always picked the one that didn’t make my head itch as much. It was metallic orange, like most of those ugly Honda Elements that seemed to be a fad for a while recently.

I wound up heading north, as I usually did, on N.H. 132 (my street, also called Mountain Road in Concord) and crossing into the town of Canterbury exactly 0.25 miles later. (I had determined this distance—starting from the mailbox that in the 1980s would fall to a redneck’s baseball bat every few years—with a combination of a ten-speed bicycle and my dad’s 100-foot tape measure, as a good Garmin watch was hard to find on the Internet back then.) I had already resolved to run through the town of Canterbury along Route 132 and to the Northfield line, which would be a first. I guessed that this distance was at least six miles, but not much more.

Despite the falling snow, the chill, and the necessary-ish encumbrance of the ski goggles, I felt solid. I was in no hurry, and the afternoon was almost windless, a detail that makes all the difference when cold powder is falling in front of your face. The yellow tint of the googles made the otherwise wintry scenery look almost post-nuclear, which I found refreshing.

But as the snow began to accumulate—in all, only about five and a half inches would be recorded in this “storm”—I began to lose just a little push-off with every step, something I knew would cause my legs to fatigue before they normally would and was probably not good for my hamstrings. Also, there are really no flat parts of this portion of Route 132 at all.

When I got to the Canterbury-Northfield line, which I later learned was 6.2 miles from home, I suddenly knew that I had to continue to the next town line, which was also the Merrimack County-Belknap County line and the end of Route 132. If I got into any sort of trouble, I could knock on someone’s door and tell them I was a teenager and stupid and—pom-pom, googles and all—tell whatever Farmer Zeke type who answered that I needed to call my goddamn mommy. If I needed water, I could get some from the sky or the ground, none of which was yellow yet. Well, through the goggles, everything kinda was.

I recall nothing special about Northfield, which is almost exactly like Canterbury. Route 132 follows the generally north-south course of the Merrimack River, but about one to three miles east of the waterway. Throughout Canterbury, I-93 carves a path between the Merrimack and Route 132. But in Northfield, the two highways criss-cross multiple times in a series of bridges. This gave me something to look at: midafternoon ski traffic, Massachusetts types who had bailed from the slopes a little early and were now enjoying a snowy drive south along I-93. One overpass, two underpasses. I expected to see them again soon.

I don’t remember looking at my watch when I saw the bridge over the Winnipesaukee River marking my turn-around point at the Northfield-Tilton line, but I would have been about ninety minutes in. I don’t remember the afternoon growing colder yet, or feeling cold—if anything, Gore-Tex was usually too much even for New Hampshire winters. I felt nothing but exaltation about getting to this spot on foot, one that seemed to take forever by car the few times I remembered coming up this way.

I felt smug and stupid at the same time when I stepped briefly into Belknap County, turned around, and started pretending I was “almost home” right away. Every distance runner has experienced this combination of benign gloating and “There might be a price for this extravagance, and soon” in the middle of an unplanned penetration of some new distance, speed, elevation, or duration frontier. Things like this meant a lot more when you had to write them down in a little notebook and only had access to other people’s special runs if they showed you their own little notebook, or texted you photos of its pages three decades later.

I remember as little about the southern trip back through Northfield as I do about the northbound leg, other than noticing the daylight starting to fade (that happens dismally early in winter that far north in the eastern edge of any time zone) and being glad that I was looking at sections of curvy, hilly asphalt instead of a long, flat unbroken line. The snow wasn’t really causing footing problems; it was kind of crunchy and safe, like granola, in those days a uniquely popular signal of healthy aspirations. But it was causing me to get tired. How much more tired than I would have been anyway—how the hell would I know?

When I got back into Canterbury, I believed it would be all downhill, an idea that became true only after I completed a climb of almost two miles, naturally with no memory of having enjoyed the corresponding descent an hour and a half earlier. Oddly, and I didn’t think of this at all during the run, I was not thirsty and would not become so until after I was done.

I threw a little party in my head for Canterbury as I started passing scenery that was part of my regular loops. A small (fewer than 1,500 people then, around 2,500 now) New England town named Canterbury cannot help but be quaint and charming, and the 03224 version is essential and not forced. Amazingly, the town already had over 1,000 residents in 1790. At 44 square miles, it boasts almost twice the land area of Boulder, population 107,000. If Eric Rudolph had known the place as well as I used to, and had chosen to hide out there instead of in North Carolina, he would still be at large, probably playing poker with Ted Kaczynski in a lean-to near Whitney Hill.

I conceived of Canterbury as the ideal place to train as a teenager, but that was because I loved running and anything associated with my personalization of the experience. But while I can make many positive arguments on behalf of certain features of the town—for example, its extensive network of dirt roads and snowmobile trails—one would be deluded to consider it a training haven. Almost the entire town is swampland, and I have never seen larger horseflies than when running down New Road (which was not new even when Christ was in diapers) in July. It is an ideal place to get shot at by a hunter, and I mean year-round, not just in traditional blaze-orange season. Even after consulting my grandfather’s topo maps before runs, I would often get lost—never without some idea where I was and how to return to civilization, but never quite where the dotted lines on the map heralding alleged paths or Class LXVIII logging roads said I should be. I usually regained civilization in these cases by emerging though some woods into someone’s backyard and picking what looked like the cleanest, fastest route back to wherever the “main road" this domicile was on—usually, two ruts—appeared to be. When I was spotted, no one seemed to care, and my passage usually drew a friendly wave, even if only a single digit was included in the gesture. I’m not sure how these unscheduled introductions-from-50-yards would have played out had I had the googles-and-pom-pom get-up going in the summertime.

Some of these ideas were not yet formed as I made my way south past Windswept Farm and down the hill over Burnham Brook and finally back into Concord. Remember, I had no idea how far I had just run; I assumed it was not much shy of 20 miles. It had taken me a shade over three hours. I don’t remember my parents being alarmed at how long I’d been out—for all they knew, I had stopped at a friend’s and decided to go sledding instead. I was dressed for it.

Before I even changed out of my clothes, I went into my dad’s workroom and used the technique I always used in those days to guesstimate the distance of a run I couldn’t yet measure by car: I took a piece of soldering wire, bent it along the length of Route 132 I had just covered, snipped the ends, straightened it against the map’s scale, and came up with about 11.5 miles.

I described this technique in a book that could have been much better had I not been off the grid and busy trying to drink myself to death in a series of hotel rooms in the summer and early fall of 2016, when the manuscript was pushing its submission deadline. From page 25 of Young Runners at the Top:

As you can tell, I did and still do take undue pride in my ingenuity here, even if the same cleverness has failed to show up elsewhere.

The next day, or soon, I cajoled my mom into driving the route with me to confirm the distance. It seemed to take a lot longer in a car. I’m serious.

According to MapMyRun, the route is 22.89 miles. Then again, we had a long driveway that I ran twice and isn’t included in the calculation, so 23 is a fair round-up. It also includes 1,445 feet of climbing, or about 63 feet per mile. Close to 3,000 feet of climb and descent in a 23-mile run on a standard state highway is sturdy work, even in good weather. My overall pace of 7:50-ish probably would have been 7:30 or better given the same effort in dry, 50-degree conditions, and probably sub-7:00 pace on level terrain.

When I returned to practice the next day, I couldn’t wait to tell the coach. I knew he would think I was a fool, but still be impressed. Both of those things seemed evident, mostly the first, but I didn’t count on him being jealous, too, which I believe he was. I remember us doing some 200s and 400s on North Fruit Street that turned into a hill at the end, and I got through those. The team captain, whose father had performed eye surgery on me almost two years earlier, declared that if I had done what I said I had done, then I should be able to run under three hours for the marathon. I didn’t think much about this, because I had only just confirmed that I could run even close to the required distance.

Sometime that week, or early the next, I got sick. This was bad timing not only because I had a race to run on Saturday night, but also because my girlfriend at the time—and is “at the time” really necessary here? Maybe—was running the 3,000 meters at her own state championship, which was on Friday night. So throughout the week, she, a senior, gave me constant heat for supposedly transmitting this cold to her. This was crap; in reality, I was lucky I wasn’t the one constantly catching germs from the other direction, at least according to increasingly urgent entreaties from friends familiar with the breadth of this spirited gal’s extracurricular behavior.

Either way, I watched her finish third in her race, and the next night she watched me finish sixth. In my heat, which only had six people. The winner, Jon Lacombe of Memorial, went out in around 65-66 for the 400 meters on that loathsome excuse for a competitive venue, and the other five people in the race, all of whom to various degrees should have just let Lacombe go, stuck right with him in a misguided cluster of head-bobbing and impending collapse. I wound up getting lapped, and several kids in the slow heat beat my time, which I think was 9:43. (Yes, you can see the top results.)

That would mark the last time I ran a poor race in a high-school track championship, though I would remain adroit at folding on the cross-country course, where I should have been stronger. That spring, I would finish second to Lacombe in the 3,200 meters at the Division I State Meet and third to Lacombe and Sean Livingston of Kennett at the following week’s Meet of Champions, where I broke 10:00 for the first time with a 9:50.1.

The next winter, as the dungeon at UNH was finally being renovated into the Paul Sweet Oval, the NHIAA moved the indoor state championships to Leverone Field House at Dartmouth College. This was a flat 220-yard track in those days, and I think the only difference now is that it’s been metricized. So, not blazing fast in its own right. But it seemed like heaven compared to years past. (I would go on to attend college at a university with an even worse ten-laps-to-the-mile concrete indoor track than the pre-renovation UNH oval.)

This time, I wound up a dogged if distant second in the state championship 3,000 meters (results). I was beaten by a kid from Salem no one really liked, and who became immediately less likeable when he arrived at the state meet with a mohawk. He had been academically ineligible for cross-country, so no one knew quite how good he would run indoors until this very day. If you think he looked like a bit of an idiot out there, imagine how everyone whose asses he was kicking felt at the time.

The boys’ 3,000 starts at 12:40 into the video below. You can see from the results that Concord tied for fourth with 28 points, all from two people and mostly from one—Chris Basha won the 1,000 meters and 1,500 meters (the former in state-record time) for 20 points, and my second place in the 3,000 meters was good for 8.

This has been a crummy week. It was hard to get many miles in because the roads and paths were treacherously icy for a couple of days. Worse, two of my friends training for the same event in Arizona next month got injured at around the same time, and they’re both out of the race. Since I am responsible for their training, I feel at least partly responsible for their injuries even though this is irrational on its face, and even though they are the kinds of runners who rush to disproportionately blame themselves. It’s hard for me to take on roles that I know I am legitimately skilled at—tutoring is one, coaching another—but include outcomes that can be wildly divorced from reasonable expectations. It’s no fun to feel like someone has gained solid understanding of a concept only to see them flub an exam, or to see someone in apparently great shape be sidelined or run a really bad race. I feel in these situations not so much like a screw-up, but as if I have not delivered the required services at all.

This is not a good way for anyone who is putting in a genuine effort to think, because anyone can engage in that guilt-charged exercise. Doctors routinely get paid handsomely for not making their patients better, and sometimes for making them sicker. Lawyers accept huge sums of money to try cases they know they will almost certainly lose. And I haven’t even started in on the people whose business is money itself.

But yesterday, when the power went out during a snowstorm, I decided to use the time to run. (Well, I was already dressed for it.) There was almost no wind, and the flakes were wet and huge. The footing was mostly sure. I could have used some goggles, and I was reminded of a 23-mile run, all on one road, that took place 35 years ago this week two thousand miles away. To be able to wander outside during a power failure and be reminded by a weather happenstance of something as formative and delightful as that unplanned adventure brings me back to what running is about. It never ends, the connections to past people and places and the tendrils that reach into the present, as long as you keep going.

The more I last out my mini-firestorms and largely absorbed and optional setbacks, the more I seem to come into contact with people with the same outlook: They just keep going. Sometimes without thinking, or needing to think.

Was that 23-miler a good idea, especially given the timing? I can’t say, but I know that action leads to experience and increased opportunities for reflection, and inaction leads to lazy dreams and persistent regrets. Maybe the run I almost didn’t do yesterday will somehow prove vital twenty years from now in ways I can’t yet appreciate.

Or maybe that unforgettable run will happen today.