Indoor track notes and reflections

The problem with trying to honor great coaches when they retire is that they never really retire

Were this 1988, the year I graduated from high school, the New Hampshire Indoor Track and Field Championships for both boys and girls would be next Saturday at Dartmouth College’s Leverone Field House. But the expansion of the sport throughout smaller schools along with an increase in the overall availability of mid-season meets for New Hampshire kids in places like Boston and beyond have helped push the indoor state championships back by three weeks, so they’ll be at Dartmouth on February 12, with the D-I meet at 10:00 a.m. and the D-II athletes starting at 3:30 p.m. Those meets will be livestreamed on NewHampshireTrackandField.com’s YouTube channel.

The top six athletes in each event will qualify for the New England Championships. The timing of the meet, which in 1988 was held at Brown University in Providence, hasn’t changed. This means that back in the day, qualifiers from New Hampshire had to wait five weeks for the New Englands if they wanted to run there, so many understandably took a pass. The gap is still an awkward three weeks, but New Hampshire kids don’t look at the indoor version of the New Englands the same way they regard the outdoor version or even the cross-country “New Englands,” which now have excluded Massachusetts for around 50 years. Many of the better ones have always cross-country skied in the winter season instead.

Five years ago, when I was still blogging on a Google platform, I wrote a post linking to a video of the 1988 New Hampshire Indoor State Championships, in which I placed second in the 3,000 meters and watched a teammate set a state record in the 1,000 meters with a hilariously ill-paced 2:33.9.

(The current New Hampshire record in the boys’ 1,000 meters is practically unbreakable; Zak Wright’s 2:27.38 in 1994 translates to around 1:53 for the 800 meters, and had he run that time on today’s Boston University track, even in whatever he had on his feet twenty-nine years ago, he might have broken 2:26 with the same effort.)

In that post, I made a throwaway mention of my coach that season. I didn’t even mention his name, even though he single-handedly allowed Concord High School to field a boys’ indoor track team that winter despite being employed at a different high school a mile away and coaching kids there in the fall and in the spring. Even as a teenager, I understood what that meant. I already understood that high-school running coaches toiled in anonymity and carried few solid expectations, all of them welcome.

All these men and (a few, in those days) women really hoped for, and this is still true of the good ones, is that the lessons they were really trying to impart—which had nothing to do with hitting prescribed 400-meter times in workouts or producing at the “required” times—managed to land on a significant number of the kids they worked with.

All any coach really owns is his or her own takeaways from whoever and whatever taught them what they knew. All any good coach hopes to achieve is to leave any situation better than it was when he or she assumed responsibility for it. This can mean taking a talented team to a title, but far, far more often than that, it means getting kids to believe in themselves and in the value of striving to be better at something that allows for easy painting within ethical lines.

Coaches don’t expect kids to give their all in every practice or even every meet. But trying to teach different kids—good, motivated kids in life and in sports—why they are leaving something on the table and how to pleasantly subdue their fears in this area is an art.

I only got a taste of this for a couple of years, but my coach in the winter of 1988 kept at the task of coaching and teaching young runners for forty-six years. His name is John Goegel. This rundown of his career encompasses the basic data, but it would have to be a 300-page book to capture the reach of Coach Goegel’s positive impact.

I wouldn’t even know where to start with what things I know John Goegel has done that will never be publicly appreciated, but that a lot of families in New Hampshire are grateful for. Goegel ended his career at Belmont High School. The district it serves—the southern end of which starts a quarter mile north of where I grew up—is hardly Mordor, but Belmonters tend to consistently present more of the sorts of off-the-books challenges coaches deal with than, say, a prosperous SAU in Connecticut or Southern California does.

Some of the ways Coach Goegel influenced me remained elusive for a long time. Thinking back on my adult-ish racing days when I was still living in Concord, I was less likely than most to show up at an event if I knew I was out of shape. In the mid-1990s, Coach Goegel started a late July race called the Canterbury Woodchuck Classic 5K, with the name intentionally evocative of a town of around 1,500 people with exactly one paved road not ravaged by decades-old potholes. The course drops so much in the first mile that the one time I broke into the fifteens at this race, I went out in 4:28. The corresponding climb to the finish in the last mile is unpleasant.

I think I have (so far) won the Woodchuck Classic race three times. But in 1999 and 2001, especially the latter, I was not at all fit. I won the 2001 race in 17:22, having one in expecting to finish outside the top five because I was pacing a high-school kid I hoped would wind up beating me. But the real reason I showed up for this race when I knew I would likely take a physical and ego beating was not just to run a race John Goegel had instituted on some of the roads I’d been running on since age 15, but to show him I was still running and trying at it.

At 53 years of age, I still have that impulse. If I woke up having been roofied and transported to a race Coach Goegel was in charge of, and was standing there bleary-brained on what was obviously starting line with only a sense of what direction I was supposed to head once I heard the right noise, I would commit to a hard effort if I saw that Coach Goegel was in charge of the diabolical scheme. (He would have been wise enough in this scenario to put Christopher Basha and Tommy Carlson in the boxes next to me.)

In my first few years of running, I used to pass Coach Goegel’s father’s house without knowing who lived there. This house had a mailbox in the form of a bulldozer, and it was so quirky that when my teammates were old enough to drive and came to my house for a run, I would take them on Morrill Road mainly for the mailbox (but also for the extended, potholey climb into “downtown” Canterbury that began soon after passing the mailbox).

Many of these physical features are gone. So is a lot of the stuff I used to see on runs through Canterbury on ruts that were carriage roads in the 1700s, including one small family graveyard that admittedly disturbed me when I first saw it because it was just in the middle of the goddamn woods. I took a rental car onto a road not really meant for automobiles out there a few years ago and saw it had been moved. I’m sure there was a good reason for this, like someone buying the land and having seen Poltergeist too many times, but this still struck me as rude.

Canterbury should never change. It really hasn’t changed much in over forty years, but it will always carry alluring memories for me because its road and trails are where I became a runner. But the Goegel family being a deeply entrenched part of the place is more than a cherry on top, and John Goegel is a great man on which to anchor positive memories.

On the subject of indoor track, just a few notes:

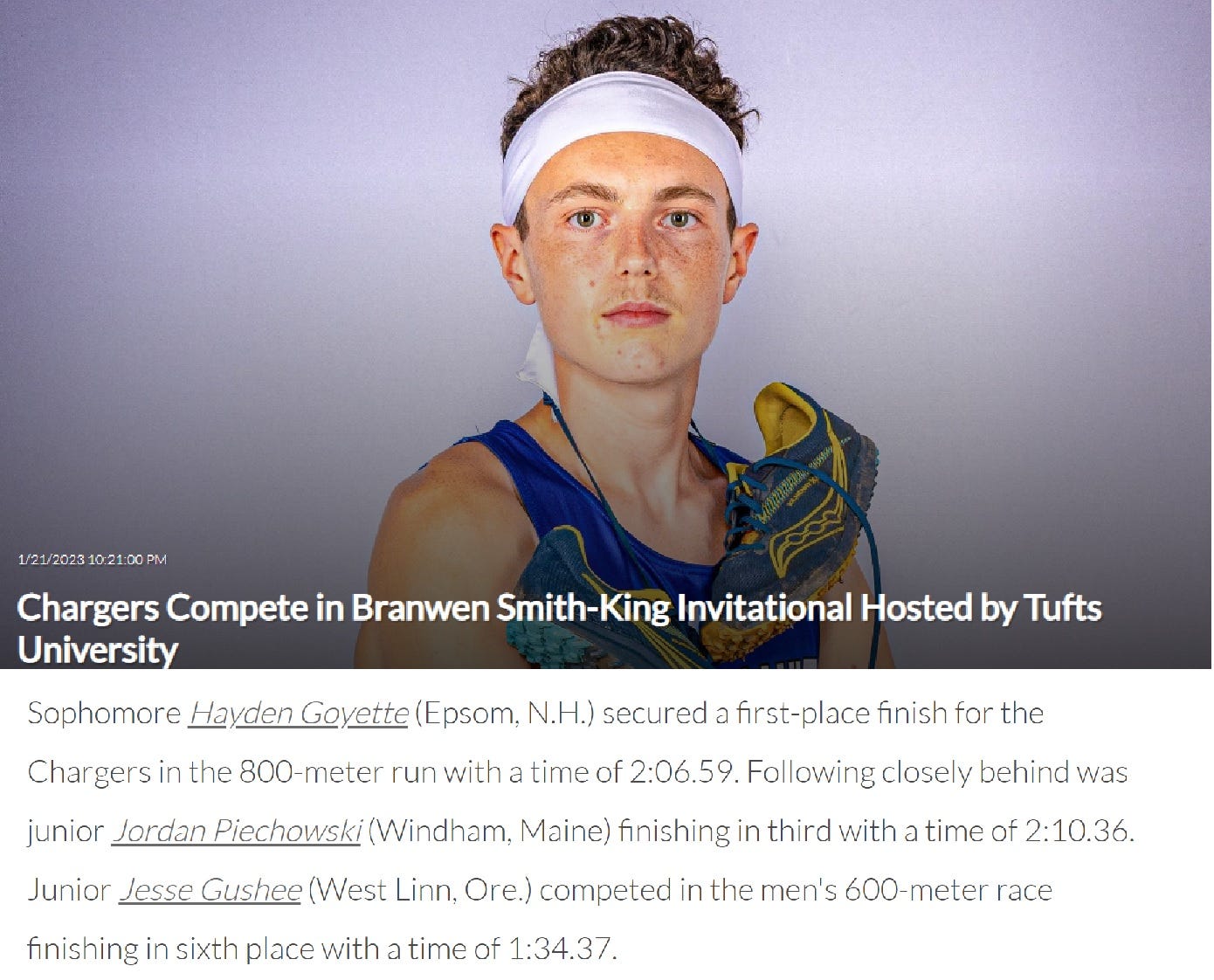

On Saturday, my nephew ran his first 800 meters since May and broke his personal best by almost a second. His best indoor time as a freshman last winter was 2:09.31, and he started college as a 2:23 kid.

He went out in 59, which means that he could run 2:04 right now if he went out in 61. He’s probably been watching too many Tom Byers or Alysia Montaño highlight reels. But he won the race by over 3.3 seconds, so his school used his photo in its recap of the action.Hayden had covid twice last year and was anemic for all of cross country, sidelining him for almost the entire fall. His best event my prove to be the 1,500 meters, but either way his times are still coming down fast.

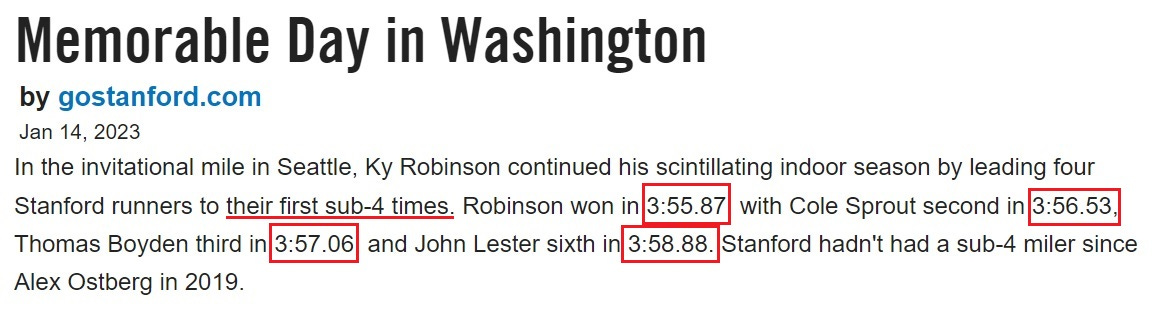

Last weekend, four Stanford runners who had never broken four minutes for the mile all did it in the same indoor race in Seattle, averaging 3:57.08 in the process.

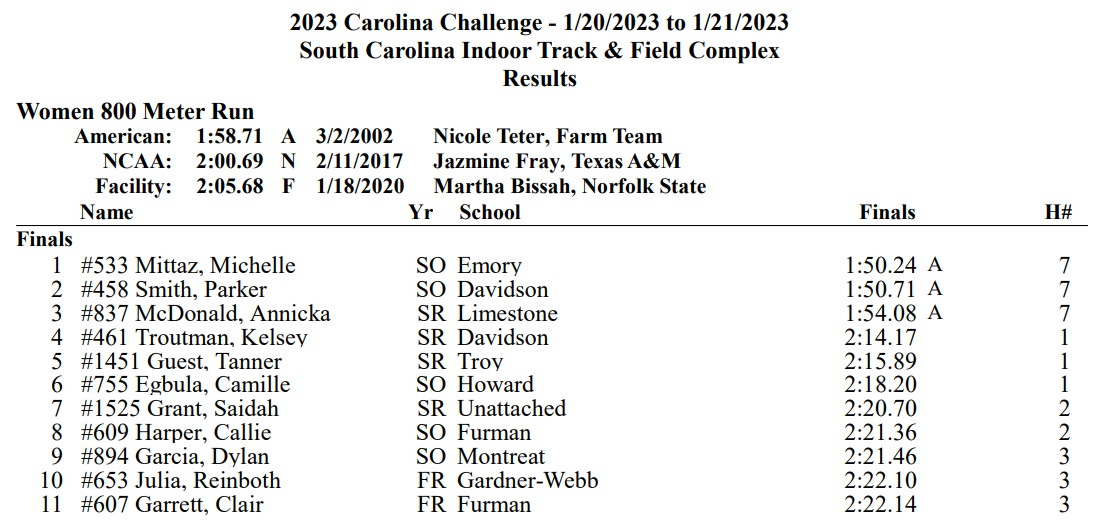

And on Friday, either three women ran some grossly underpublicized 800-meter times out of the seventh heat in a meet in South Carolina, or something else happened.