Infiltrating the Runner's World "Join the Movement" issue (III)

Praise is due for a refreshing journalistic ride, but someone didn't check the indicator lights carefully

I’ve been slow to wrap up this miniseries of posts about the November/December 2020 “Join the Movement” issue of Runner’s World, which includes a twenty-year-old Running Times (R.I.P.) article I wrote about tempo runs. (This month, actually, I’ve been slow to wrap up lots of discretionary stuff; I often blog when I should be prioritizing other things, but when I do get around to triaging what’s in my life’s waiting room, I tend to notice how much disinfecting, suturing, and even amputating I’ve been neglecting.)

As a result, at least one of the issue’s signature stories has been significantly affected by the behavior of one of its subjects. Knowing this would probably happen was, in fact, one of the reasons I’ve been dragging feet on the series (#1, #2) for a couple of months. I doubt anyone even notices when new creative branches of the blog randomly appear, only to see me leave them infrequently nourished or untended altogether. But readers do notice when developments occur in the more delicate topics I’ve started to indelicately explore, and are happy to serve as provocateurs by providing links I otherwise may never have found.

The issue’s centerpiece is an article that profiles five women, each facing a different operational challenge in running as well as everyday life. Selected as the initial members of the Runners Alliance, each woman is active in combating other people’s bad ideas about important aspects of who they are: Lesbian, Asian, Indigenous, Black, and fat. The author, meanwhile, is Taylor Dutch, who was assigned not just this article but one of whitest names in history.

All kidding aside, Dutch and the editors did a great job with the concept of promoting a more welcoming running environment at no one’s expense. Dutch’s writing here and elsewhere is fluid and crisp, but that’s just the easel on which she lets others do the painting; importantly—no, critically, given the deterioration of her professional niche—Dutch lets the five women tell their own stories without salting their narratives with value judgments, pro or con, or gratuitous sidebars about alleged evildoers. Also, it is a very difficult task for any writer to portray, from the outside, what a particular brand of loneliness, the kind often made worse by being in a sea of smiling people, really feels like. I’m no stranger to such feelings, but have found them hard to translate into the right words even for personal journaling or essaying purposes, much less work with another writer about them. With this batch of stories, not only does Dutch successfully serve as a skillful navigator of someone’s else’s difficulties and trauma, she does it five distinct times.

Also, most of these stories reflect, even epitomize, what is supposed to be meant by “social justice” efforts. As you’ll see, the women in the profiles are not just randomly chosen targets of selective social suffering; each has taken some kind of directed action on behalf of not only themselves but people they speak for (you’ll note the exception). There are formal corporate partnerships involved. Better still, there is no sweeping contempt for anyone judged to be automatically involved in the setting up of an unfair society for people of color, especially women. This presentation is not someone throwing gasoline an existing barn fire just to say they were there when the whole hoary structure came down; it’s the opposite, seeking to build on an imperfect but existing foundation. (For an example of a really, really awful story in the strict SJW vein, see this chum-blast in Trail Runner. I hope providing that simple link will spare me the joy of reviewing the mess at the other end; there’s very little bleak humor I could add that won’t be immediately evident.)

The Five Anti-Harassment Profiles

I was very happy to see two-time U.S. Mountain Running Champion Addie Bracy (“Addie” is not short for anything; I asked, and recall litigating the result) heralded for something other than her considerable running accomplishments. I met Addie almost ten years ago, not long after I washed up in Boulder. At the time, she was mostly a (very good) track runner and one of the de facto leaders of a now-defunct local club that had a couple of great years before people scattered for various reasons (that doesn’t narrow it down one bit here in the 3-0-3, but wait for it). I used to see the group at the track and occasionally work out—in very time- and effectiveness-limited spurts—with them, and count a number of its then-members among my friends today.

It doesn’t surprise me to see Addie being willing to put her name to a cause larger than herself. Some of my own friends have been able to lean on her in rough times. And in the second half of 2016, when I was on my last protracted bender, roaming the state’s hotels and hospitals and essentially unavailable, she stepped in to add insights to the nearly finished manuscript of Young Runners at the Top. My disappearing act badly damaged what could have been a much better book, but Lize and Addie’s work helped mitigate the effects of my absence.

As a means of establishing an unearned connection to one of my betters, I like that Addie has excelled at running up a mountain I used to ski down. These days it would probably take me longer to get from top to bottom on skis than it would take Addie to get up it on foot, though maybe not in snow, and she’d be far less worse for the wear afterward.Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel’s efforts are another reminder that the U.S. has left its Indigenous people behind more than any other citizens, and it’s not even close. Every time I read an article about someone doing work within this community, I learn a brand-new crushing statistic or two.

In the second year of my incomplete but not-altogether-valueless participation in medical school, an undergraduate friend at the same institution committed suicide on the same 1995 weekend I was away in Massachusetts running my second marathon. The previous Saturday, he had called looking for my roommate, with whom he had a closer connection, but my roommate was gone, so Phil and I that night wound up talking for about an hour about what he called his “girl problems.” This spontaneous conversation ended on what seemed like an okay note, and a week later Phil was gone. That was my first real experience with “What the hell could I have done?” (I had forgotten until now that Dartmouth had a mini-run on student suicides that fall.)

The greater point is that I attended a memorial service for him at the Native Americans at Dartmouth house on campus, and if you have ever had a related experience as a basic clueless white person, you can grasp why this underscored for me the tremendous difference between what prayer means to an Indigenous person and its cheap, post-mass-shooting application in everyday American discourse. I have some appreciation for how much her marathon ritual means to Daniel at a human level even if I could never replicate it in the same way.If I understand her mission correctly, Carolyn Su can best be described as a conduit through which underrepresented runners can more easily relate their stories to the broader running universe. Su is great with words, and none of them are weighed down by the metaclaptrap lingo that, along with being unmoored from reality, marks SJW-type “activism” as the societal malignancy it is. It’s got to be really hard pushing for desirable changes when facing SJW antics on your own supposed side and both traditional racists and SJW-critics like me on the other; this requires a rhetorical threading of a needle of which I would not be capable, as I’d become too discouraged by all of the noise from every direction.

One thing I’ve honestly long wondered about, and this probably is at least partly attributable to some kind of undeniable “privilege,” is why people continue to see road races as gatherings of principally very thin or at least unusually fit-looking people. This may have been somewhat true in the 1980s, but my first impression of any typical road-race field is that it draws more people who just look like everyday people: Some fat, some thin, some swole, many with dual bolted-on chest weights in Florida, most somewhere in between, with an expected skew at the front of the pack toward hollow-cheeked anorexics and bug-eyed neurotics (which are often overlapping categories, spanning the sexes and genders). If you’re there with a number on, even the fastest, most serious-looking fellow entrants see you as one of them. Especially if you look scared to see someone who even looks fast, because all of us have been through the uniquely troubling experience of lining up for our first-ever race.

Claire Green is as delightful a person up close as she’s described in her profile. She went to high school one town over from Boulder, and I met her around five years ago, when she showed up for one of the summer all-comers meets at the University of Colorado track. As memory serves, before her race, she was bouncing around beaming and telling people she was “trying the 1500!” like she was just happy to have made it to a track meet to see what the deal was. Then she went out and ran a high-altitude 4:30 (she would have just finished her freshman year at Arizona, I believe) before resuming her chatter-fest. She seems to be someone with the vexing natural characteristic of having an infectiously positive personality.

Green is a contributing writer to RUNGRL. Please remember and return to that site, because it’s a good one. It deals, helpfully, in empirical, actionable facts—for example, “Black women (and their families) are suffering from health disparities at alarming rates in the U.S.”On the cover of my copy of the November/December 2020 issue is Latoya Shauntay Snell, whose primary platform is “body politics,” which in her case seems to mean, well, not a comprehensible thing. She finishes or claims to finish marathons in the seven-hour range, and operates a site called The Fat Running Chef. Her would-be platform arises from a probably apocryphal tale about being heckled by a spectator during the New York City Marathon. Who the hell gets several marathons into their running before catching a “HEY, FAGGOT!” or a cascade of oinking from a bystander or passing car? It took me about ten minutes, but then most of my earliest running transpired in a more rough-and-tumble town.

Snell’s inclusion in this article comes perilously close to firing a torpedo through the hull of an otherwise noble enterprise, because, whatever else her colorfully decrepit antics add to the running world, she is the precise antithesis of an anti-harassment activist. Not just here and there but floridly and by explicit design. She is a liar and a gaslighting fool who, like the Donald Trump that supporters of Snell uniformly detest, will at any time blurt out whatever is most likely to lead to more donations from online suckers.

When she feared that Derek Murphy at Marathon Investigation was planning to write an article about one of her deceits, she tried to get ahead of this putative exposure by courageously lighting up Murphy on her own Facebook page with a farrago of bravado and misdirection. It appears likely that had she not done so, he wouldn’t have written a word about her; really, she’s too damned slow to be interesting even as a cheater. But because she went on a lie-bender, he did. (The one thing I would suggest to Murphy about his methods is that he not engage with any of his putrid, high-follower subjects on Facebook, at least when someone else is controlling the conversation and its “facts.”)

My favorite part of this extended salvo from Snell is either her referring to a commenter’s [note: This is corrected from “referring to Murphy’s”] “Quaker Oats ass” or complaining that her 11-year-old reads about her on the Internet while using the phrase “I’m being fucked with no lube.”

Snell, you see, calls herself an influencer. This is somewhat new term describing someone who has no traditional job and instead makes—or aims to make—money online by serving as a geyser of either tits-and-ass or “edgy” opinions. I’ll be writing a separate piece for subscribers about this influencer and the general phenomenon, because she makes me see too many people in running as garden-variety, knee-walking dupes and pom-pom-waving idiots. But for now, I’ll just say I have never once seen an instance in which a company has attached itself to someone running so obvious a con as Snell and wound up better for it. Yet despite HOKA ONE ONE recently opting to discontinue its sponsorship of the New Jersey-New York Track Club, it maintains a professional relationship with this gibbering clown.

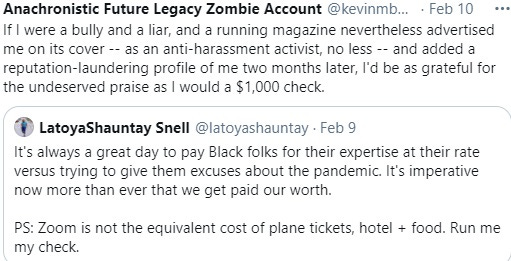

And what do you know? Despite being flattered and in fact misconstrued over a period of months to her extreme benefit by Runners World, Snell announced on February 5 that she was quitting the Runners Alliance. In a live Instagram story that disappeared as soon as it was streamed, she reportedly complained that Runner’s World wasn’t paying her for her role and also hadn’t prevented people from linking to Murphy’s article about her from the Runner’s World Facebook page. That’s why said Alliance now lists four members.So much for the sincerity of her speaking out for the voiceless! And a special curiosity is that Dutch went to some trouble to cultivate a relationship with Snell—there was this RW piece separate from the five-profiles offering, and the pair appeared on a number of podcasts last year (I didn’t listen to a single one and wouldn’t if you paid me.)

I have called this in some way many times in less than six months of focusing my blogging on ruinous dynamics such as these, and I’ll be happy to do so when it happens again, but once more: SJW antics are invariably a power-attention-and-money grab, not earnest activism. This means that fragile alliances and bridge-burnings are inevitable and easily foreseen features of any relationships forged with such people, whether they call themselves influencers or not. And whether it’s trashing someone’s reputation for sport after stiffing hundreds of contributors or publishing op-eds by ardent Nike critics who race in Nikes, the results create a silly, ramshackle look for the host publication (on top of, in the case of Snell, a lot of wasted verbal and photographic effort).To all influencers, the deal is this: You can have your influence, sure, but you don’t get to influence the character of that influence. If you act too much like certain lowbrow individuals I’ve dealt with in the past, using your cellulite or melanin to bulldoze through all concepts of basic decency, I’ll be happy to go to great lengths to contribute to the immolation of your scam. It’s pretty easy to humiliate people who advertise how many weak spots their alleged armor actually boasts.

Snell fought her way onto the cover of a running magazine the way a lot of people have achieved what passes for respect these days: Through a combination of bullshitting, bullying, self-contradicting stories, and scrambling to protect the laff-riot reputation as a decent human various major entities in running have granted her. And if she wants to whine about money, well, Runner’s World didn’t pay me to provide them a new head shot (which looks great), or review their edits of my musty article (which I did with utmost care) or supply a detailed bio (laden with details to harden the laziest nipples) to go with the piece. I didn’t expect them to, because I understand the economics of these publications.People like Snell are to “movement politics” what Michael Avenatti was to anti-Trumpism circa 2017. He gave a lot of liberals desperate for a big-talking ally reasons to overlook that what they were seeing was no more than another version of Trump himself, that is, a showman, a thief and a beaming douchebag.

Again, I’m probably not done with this, as I’ve barely scratched the surface of how awful a spokesperson Snell is for literally everything except reckless, childish (but far from dumb) conduct; my one kindness of the year will be limiting the audience of the upcoming braying. The fourth and final article in the “Join the Movement” series, meanwhile—the writing of which I believe will provide me with the most incendiary form of unkind fun I’ve enjoyed in some time—will examine the question: Just what constitutes a “reputable publication”?