IT'S OFFICIAL: The most remarkable track athlete of the 2024 indoor season at any level was probably Quincy Wilson

Also, how many sub-ten high-school girls is too many? With all-time distance lists now featuring ephemeral half-lives, should we prevent these girls from even training until they're at least 13?

When I find myself perusing elite-level high-school running results and performance lists, I usually gravitate first toward the two-mile run or whichever of its closest relatives (the 3,200-meter run and the 3,000-meter run) features in the data. (Two miles is in the neighborhood of 3,218.69 meters.) This may have something to do with these being my own events of choice in high school. And I usually look at the girls’ results first, because the times of the fastest-ever U.S. girls correspond closely to my best times, whereas the best boys run considerably faster for two miles than I did for 3,000 meters.1

The all-time U.S. high-school girls' indoor two-mile list took a beating two weekends ago, when two competing American national indoor track-and-field championships were held. Below is a snapshot of Milesplit’s all-time top performers heading into the 2024 Nike Indoor Nationals and the 2024 New Balance Indoor Nationals. (It’s worth noting that this excludes converted 3,200-meter performances, but the two-mile seems to predominate over the 3,200 meters in American high-school indoor meets of supra-regional consequence.)

Four of the top 10 heading into the NIN and NBIN gatherings have been pushed out. Elizabeth Leachman is now #2, Allie Zealand is #4, Isabel Allori is #6, and Jane Hedengren is #7. Melody Fairchild's 9:55.92 was a national record when she ran it thirty-three winters ago, but after this weekend she's “merely” the #3 all-time performer from the state of Colorado, trailing Allori, who’s from Fort Collins, and Addison Ritzenhein, who attends Niwot High School.

Also on the Colorado front, Bethany Michalak of Air Academy—who took second to Ritzenhein at last fall’s 2023 NXN Cross-Country Nationals, but whose team edged out Niwot for the top podium spot in Portland—ran a 4:48.36 mile at NBIN for 7th place. I didn’t look compare all of the disciplines, but it seems that this winter, New Balance’s championship drew far more competitive fields than Nike’s did.

Maybe the most impressive thing about these times by Colorado girls is that the CSHAA does not recognize indoor track as a winter sport. And it shouldn’t, because between the infamous black ice of I-25 and often-closed mountain passes, no one should be driving around Colorado in the winter without a genuinely good reason, like heading to Breckenridge to get stoned on a slow-moving chairlift in preparation for high-speed battle with the moguls and snowboarders beneath. But in addition to sparing a few teenage lives, this norm probably winds up sparing a lot of future careers. Even highly selective elite high-school runners now run a slew of cross-country invitationals and “post-season” meets, and it’s tempting for these kids to just roll unfettered from September to June without a genuine break from racing.

The most remarkable individual achievement came in the boys’ 400 meters at NBIN, where Quincy Wilson, a sophomore from swampy Potomac, Maryland who turned 16 in January and could pass for a wise 14-1/2, ripped a 45.76 to win the event by 1.45 seconds.

A half-second margin of victory in a national boys’ 400-meter championship is noteworthy; winning by close to three times that is probably a Black Swan event.

Wilson has been recording shockingly precocious times for a male long sprinter for years. As a freshman last June, he placed second at the 2023 New Balance Outdoor Nationals and ran 45.87 three weeks later at the 2023 USA Track and Field Under-20 Championships. That mark ties Wilson for #38 all-time, per Milesplit.

According to the most up-to-date World Athletics points calculator I could find, created by Jeff Chen, Wilson’s 45.76 “short track” time is worth the same 1,190 points as a 44.86 outdoors. The all-time outdoor U.S. boys’ high-school list features three sub-45-second performers, with Darrell Robinson’s national record pushing 42 years old.

Wilson and his 45.76 in Boston wound up the 2024 indoor season in a tie with 31-year-old Vernon Norwood for #26 in the world and #15 in the United States in the 400-meter dash.

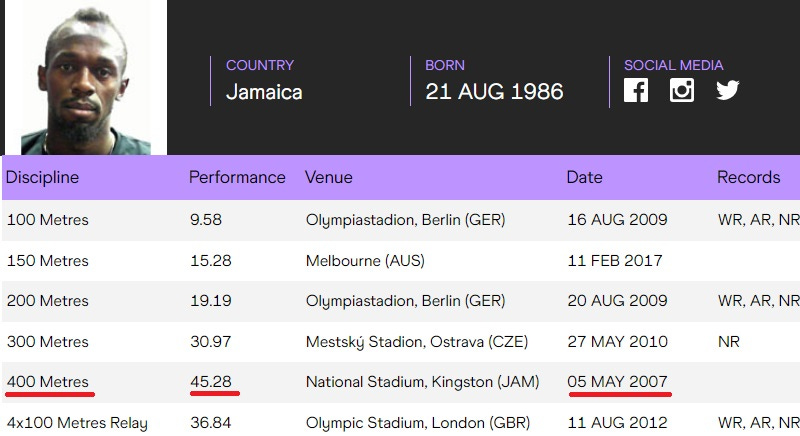

While Wilson is clearly bound for sub-44 status as a teenager unless he becomes derailed by injuries or externalities, we* mustn't forget about another apparent North American prodigy who in April 2003 ran 45.35 in an outdoor 400-meter race at the age of 16 years, 8 months—and then essentially did nothing for the rest of his one-lap career. This athlete failed to improve this time even a tick until he was 20, when he mananged a 45.28. That was as fast as he ever ran.

Ideally, Wilson will receive consistently focused guidance as he progresses through his teenage years and develop into something better than one more 45-and-change teenage quarter-miler who could have been an Olympic medalist in the event, but wound falling prey to sundry distractions and is now at best a track-and-field footnote.

My best time for 3,200 meters outdoors was 9:43.3 (about 9:46.8 for two miles), which in the spring of 1988 was good enough to outkick the previous fall’s Division I State cross-country champion in a dual meet. I also ran 9:43 or 9:44 at that year’s New England Outdoor Championships, a time that, bizarrely even for those days, was good for 11th or 12th. It was in the high nineties in American temperature units at Boston College that afternoon—I remember all of us smelling unusually bad as a result from our armpits and asses as we squinted through sweaty tears waiting for the musket to be fired—but that’s irrelevant even if true because every middle-aged guy claims the weather, the track, the officials, or all three were shitty for all of his meaningful meets.