July 22, 1987: Said Aouita becomes the first man under 13:00 for 5,000 meters

Aouita remains among the few at his level whose desire to win included a willingness to defy the supposed limitations on his own competitive range

(This is the second post in a dedicated series of ten.)

When I heard the news on the radio one summer morning in 1987 that Said Aouita of Morocco had dipped under the thirteen-minute barrier for 5,000 meters the night before, it shouldn’t have grabbed me by the guts the way it did. Aouita, after all, was the reigning Olympic champion and had already run 13:00.40 two years earlier, the first of the batch of world records he world secure over his splendid career.

But what Aouita had just done at the Bislett Games in Rome was all any top runner can do, and that was eliminate the small but critical gap between imagination and reification. And for me, something about hearing the “twelve” to lead off Aouita’s time was electric. Just because something previously unachieved is by any standard inevitable doesn’t mean you know exactly when it’s coming, or what wheels will start whirling within your psychic glee-centers when it happens.

I was then 17 and training well for my senior season of cross-country. Less than a week earlier, I had run a still-extant five-mile road race in 27:24, beating a teammate, one of the best runners in the state, for the first time. When I was coming up through the ranks, whenever I heard jazzy tidings from the competitive running world above me, I channeled it into my own resolve to blast into new, albeit far humbler, territory.

When Aouita loped his grimacing way into the twelves, my own best 5K performance was a 16:15, run on the roads a few weeks earlier on the Fourth of July. 5K would stop being my favorite distance the instant I officially completed the twelfth grade, which, as this dapper yearbook photo from the summer of 1987 reveals, was when I was nearly twelve years old.

But in high school, cross-country was my favorite sport, even if it occasionally had its grunting, buttwise way with me in the back seat of a pale-yellow, rusted-out 1977 Chevelle. That preference, especially as a mathlete, meant becoming pathologically familiar with every way in which the 3.10685596119-mile distance could be broken down mentally and recombined into something more arithmetically pleasing.

I had regular access to printed and bound reading materials as well as various buildings on paved roads where these were kept for rental or purchase. In the course of my research, I learned that it had taken humankind 23 years to go from the first sub-14:00 (1942) to the first sub-13:30 (1965) and now 22 more to grab its first sub-13:00. That neat, linear timeline in isolation predicted a sub-12:30 in around 2010. I deemed this achievement unlikely, more out of basic disbelief than out of any rational concept of when and at what performance level the men’s 5,000-meter improvement curve would inevitably begin flattening. But given Haile Gebrselassie’s 12:44.39 in 1995 (history’s first sub-12:50) and Daniel Komen’s dipping under 12:39.74 in 1997 (ditto for 12:40), things were actually ahead of schedule on the “12.5 in under 12.5” front for a while.

But not for much longer. Although the men’s 5,000-meter world record has been improved three times since Komen’s romp—in 1998, 2004, and 2020—it now sits at 12:35.36, having been eased downward by only 1.99 seconds in the past 17 years. That is, the improvement curve didn’t “begin flattening” at all; it snapped almost to the horizontal toward the end of the previous century. I don’t want to suggest that a mammoth EPO controversy at the 1998 Tour de France and the 2000 development of a reliable test for that drug helped put the kibosh on all that fun, but according to historical sources, those things did happen, and knowledge of them was not contained to innocent bystanders.

I had watched Aouita’s 1984 Olympic 5,000-meter victory on television, days before taking up the sport myself. One of the most likely and blondest reasons the Moroccan chose the event is shown in the center of the photo below, from the first-ever World Athletics Championships in Helsinki in 1983: Great Britain’s Steve Cram.

The rangy former footballer was clearly forming up to be the 1,500-meter athlete to beat the following year in Los Angeles. While Cram would be beaten back into silver at the Olympics by defending champ Seb Coe, Aouita’s switch to the 5,000 meters paid off large.

Aouita took another crack at the metric mile and Cram in July 1985 in Nice, dearly hoping to become history’s first sub-3:30 man after nearly becoming its first sub-13:00 man at the distance he’s best remembered for. He left France with a new, eyeballs-out 3:29.71 on his resume’, but Cram went home with the win and the world record (3:29.67). Determined to make utmost hay of his superior fitness, Aouita claimed the world record the next month in Berlin with a 3:29.46, a mark that would stand for over seven years. That came just two days after Aouita missed Cram’s weeks-old one-mile world record by 0.60 seconds with a 3:46.92 in only the second sub-3:47 ever.

In 1986, Aouita used the non-Olympic, non-World Championships year to do what good runners do and venture outside his comfort zone. In an intensely anticipated 10,000-meter debut at the Bislett Games in July, Aouita took a spiking, but won easily in 27:26.11, then the sixth-fastest performance in history and within 13 seconds of Carlos Lopes’ Fernando Mamede’s world record. The following month, he missed Henry Rono’s 3,000-meter world record (7:32.1) by 0.44 seconds. Four days later, he ran the distance again and missed the record by even less (0.13 seconds).

Then came Aouita’s 1987, which saw his 12:58.39 come soon after a world record at 2,000 meters (4:50.81). He won the 5,000 meters off a slow pace at that year’s World Championships in Rome, pocketing the second of his two gold medals in outdoor global championships. He also took another stab at Cram’s still-standing mile world record, missing by 0.44 seconds but easing his personal best down to 3:46.76.

All of this somehow inspired Aouita to select an 800-meter/1,500-meter double attempt at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul. Aouita had run 1:44.38 for two laps in 1983, quick but not indicative of a real chance at a medal, especially since he would be racing another event. Aouita came to South Korea hampered by a hamstring issue, but also having just lowered his 800-meter best to 1:43.86. He would wind up scratching from the 1,500-meter final, but clawed his way to bronze in the 800 meters in 1:44.06, the second-best time of his life.

Aouita thus became and remains the first man to hold Olympic medals in both the 800 meters and the 5,000 meters.

1989 would prove to be Aouita’s last productive year. When he broke Rono’s 3,000-meter record with a 7:29.45, it made him the first man to break 1:44, 3:30, 7:30 and 13:00 in his four primary track events. Thirty-two years later, he’s still the only athlete with that distinction.

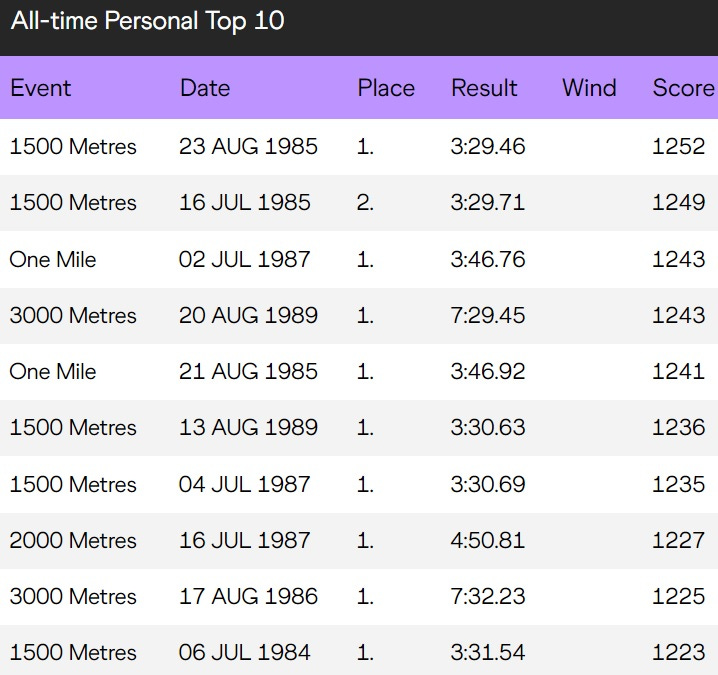

What’s interesting about Aouita’s career, considering what inspired this post, is that seven of his ten best performances, per World Athletics points, came in either the 1,500 meters or the mile despite his never appearing in a global 1,500-meter final after 1983.

When you’re a teenage distance runner, it’s very easy to idolize a 5,000-meter world-record holder. The distance is relatable, and if you lack leg speed compared to other distance folk at your level, it’s alluring to imagine more kinship with the kind of runner forced to grind out victories rather than have the luxury of sprinting away to them.

But in reality, the 5,000 meters was probably not Aouita’s best natural distance. He was able to win and set records at that discipline because in his era, A-list studs were harder to find in the longest track distances than in the 1,500 meters, and Aouita was simply brilliant at everything. Steve Cram is one of the best 1,500-meter runners ever to stalk the planet, and Joaquim Cruz was a flying yellow-and-green 800-meter monster; not taking the measure of either of these men at their signature distances is to no athlete’s shame.

It would have been a treat to see Aouita in more 10,000-meter races, or better yet in a few cross-country races, which carried more prestige back then than today. But what he did indeed accomplish, usually eyeballs out and always with manic purpose, was enough to make an impact that has yet to be erased or even much diminished by the sands of time.