August 5, 1984: Joan Benoit wins the first Olympic Women’s Marathon

I am not worthy, but here we go.

(This is the first installment of a ten-part series about influential happenings in long-distance running since the 1984 Summer Olympics, which concluded days before I officially became a part of the sport.)

William Faulkner, himself no slouch with a pen, referred to Mark Twain as the father of American literature. In the same tradition of crediting a single rarefied performer with inspiring subsequent generations to redefine the limits of a special niche, Joan Benoit Samuelson is the undisputed mother of American world-class road running, and at 64 stands as its grande dame.

Benoit Samuelson is probably best known for winning the first Olympic Women’s Marathon, which started at 8 a.m. local time on August 5, 1984 at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Only 50 women from a mere 28 countries were on the line, but it was an enormous moment. This wasn’t “merely” the first Olympics with a women’s marathon; it was the first with any women’s running event longer than 1,500 meters, which on the track included only a flat 3,000 meters. (The 10,000 meters would be added at the next Summer Olympics, in Seoul; the 5,000 meters would not replace the 3,000 meters until the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta.) The 1984 Olympics were also the first to offer a women’s 400-meter hurdles.

I was 14, soon to start the ninth grade. I had been watching the Olympics for a week already, mostly gymnastics, but this women’s marathon was the first “athletics” competition of the Games. I might have been prodded four years earlier into paying attention to the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow had the U.S. not boycotted them, because even at ten I liked watching sports on television (mostly hockey, because I believed in miracles). But to my memory, I had watched none of whatever coverage had been offered from what was then a massive country known as the U.S.S.R.

These Olympics were during the last stages of the Cold War, and every Eastern Bloc nation other than Romania had answered the 1980 boycott with a snub of its own of the L.A. production. At 14, I didn’t much care, and most of the competitive dilution of these Olympics had been back-burnered by the unprecedented glitz of the opening ceremonies, which had even featured a guy floating around with a jet-pack, and also saw a black person light the Olympic flame at the end of the torch relay for the first time in history, 1960 decathlon champion Rafer Johnson. The point being, the IOC and the USOC endeavored to create an unprecedented level of pure viewing entertainment at the 1984 Summer Olympics as well as continue the tradition of extracting every ounce of drama from its contests. And it worked, probably on adults as well as teenagers. Even in gymnastics, I was under the impression the whole time that the Americans were beating the best gymnasts on the planet. Something like that happened, at least.

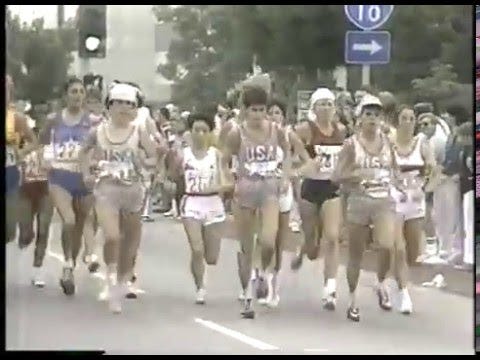

As hard as it is today to not associate the five Olympics rings with NBC’s peacock logo, ABC had the broadcasting rights in L.A., and Al Michaels, Katherine Switzer and Marty Liquori were the announcers. In the clip below, which shows the first fifteen minutes or so of the race, that’s Liquori explaining why so many athletes opted for light-colored singlets, and that’s Switzer marveling over the training of the early leader, a Japanese.

I was, of course, absorbing none of these details in real time, as I was over a week away from taking up running myself. This entire account is unavoidably a mishmash of actual impressions and the results of immersing myself in distance running for the past 37 years or so, but I’m doing my best to keep things in the right boxes. For example, I do remember it being a big deal that women now had an Olympic marathon (though I couldn’t really see why it hadn’t always been that way); but only decades later could Liquori’s comment “Other than the Olympic Trials, we’ve never had an opportunity to cover an all-women’s race” make my eyes mist up, because a lot has happened since, most of it connected to fond memories both personal and general.

The marathon race continued well past fifteen minutes. In fact, there are dozens if not trillions of admiring and thorough online biographies of Benoit Samuelson’s 1984 Olympics win, and the first thing almost all of them mention was her break three-plus miles into the race and how experienced observers matter-of-factly labeled it a suicide move. Some still seem to wonder if it really worked.

Oh, I might have left something out. To get to the Olympics, Joan Benoit Samuelson—then Joan Benoit, now often just “JBS,” and all along the athletic world’s most famous “Joanie”— had won the Olympic Trials seventeen days after undergoing knee surgery. That is not an unheard-of thing now, perhaps, but is still uncommon. It was not a remotely normal thing to try in the relative infancy of arthroscopic surgery, then as mysterious and foreboding a term to runners as “artificial intelligence” would become to tech pundits decades later.

That groundbreaking 1984 U.S. Olympic Women’s Marathon Team Trials in Olympia, Washington had featured the deepest marathon field of all time, including a 16-year-old from New Hampshire named Cathy Schiro who briefly surged into fourth place late in the race before finishing ninth. The Olympic field, obviously, was notches deeper. Benoit Samuelson’s personal best, also then a world best, was 2:22:43 from the 1983 Boston Marathon, when she famously went through 10 miles in under 5:10 pace and halfway in 1:08 and change. But as other times from that race underscored, that performance had come with the benefit of a tailwind—one that was then impossible to properly quantify, but that keen observers tried to account for. And the fact that she’d beaten back serious knee bedevilments once lately was no assurance she was equipped to do it again.

Benoit Samuelson never faltered and won that Olympic race in 2:24:52, finishing over a minute ahead of Norway’s Grete Waitz and more than two minutes ahead of Portugal’s Rosa Mota, surely one of the most ebullient marathoners ever. Norway’s supernaturally economical Ingrid Kristiansen took fourth. [Note: the e-mailed version “awarded” the silver to Mota and the bronze to Kristiansen, omitting Waitz altogether.]

Benoit and Kristiansen would take up a thrilling rivalry the next year, when Kristiansen set a world best of 2:21:06 in the spring in London, then faced Benoit Samuelson and Mota in Chicago in the fall. In the Windy City, Benoit Samuelson again prevailed, setting an American best of 2:21:21 that would stand for 21 years until Deena Kastor’s 2:19:36 in London.

It’s tempting to go on to describe every significant event in the JBS canon, but more pertinent is the effect this had on my own running. And that effect was quick, multiplicative, and lasting, thanks to the presence of a pair of other New England women who were even closer in space to me at the time.

I don’t think the 1984 Olympics were what prodded my mom to suggest I try cross-country in the week after the closing ceremonies, but try I did. At practice, the coach and the older kids talked about “Joanie’s” Olympic victory. The next fall, a Concord High graduate and Boston University runner named Barb Higgins—who still holds the CHS 1,600-meter record with a 4:56.1 from 1981 and who gave birth this year at 57, a tale for another day—occasionally joined our team for runs when she was in Concord. She had been recruited by Bob Sevene, Benoit Samuelson’s coach, and been coached by him for one year before “Sev” took over as head coach of the Nike Athletics West team in Oregon. Higgins had met Joanie along the way, and regaled us kids with stories of her interactions with world-class runners. In the pre-Internet age, this was, like, a totally rad deal.1

For me, it was part of a greater phenomenon. My junior year, I was introduced to Lynn Jennings, who was a close friend of another Concord High grad and who attended some of our meets that fall. Jennings lived in Newmarket, about 40 miles away, and while she was not yet the runner who would claim three World Cross-Country titles and set an American record in the 10,000 meters, she was still awfully good, having won the first of her nine national cross-country titles the previous year. After I broke into the top ten at the Manchester Invitational—really the first time I had made any sort of impact on the modest local prep scene—Jennings personally congratulated me in the chute. I now suspect this was orchestrated and if so, I know the culprit’s identity. But that moment, that big “You put everything into that finish!” delivered with a beaming smile made an indelible stamp on my identity as a runner: Someone who was really good thought I might belong in some way to the same club she did. As my mom will attest, I talked often of wanting to be as good someday as Jennings, who kicked my ass a few times in New Hampshire road races before I graduated in 1988.

As the years progressed, and my own running in with it in fits and starts, another arrow in my motivational quiver was provided in the form of Schiro’s ascendancy to the to the top of the U.S. marathon ranks. I had watched Schiro as a sweats-toting freshman at the 1984 New Hampshire Cross-Country Championships, when she was en route to winning the Kinney (now Foot Locker) National title in San Diego, and could not believe anyone could win a 5K race by as much as she was winning them, her expression seeming to show more boredom than effort. (Later, I realized how easy it was to confuse detachment with exquisite concentration in the expression of a human athlete.) As Cathy O’Brien, she continued living in Dover, where my parents have lived since 2004, throughout the 1990s. She made two Olympic teams in the marathon and set a world record for 10 miles, and her singular focus on road racing was something I could relate to at my far more modest level.

If I have done a poor job of describing how these people and events created a cascade of unremitting reasons in my mind to want to improve as a runner, hopefully the fact that I have tried is convincing enough. I’m just lucky to have wandered across all of it by being in the right place at the right time, and with, critically, the right “mid-level” people around to create meaningful connections between my own endeavors at the elite world. Few of us can be world-class, but a lot of us can be world-class “mid-level” types who strive to see the most interested young runners put in contact with the ideal sources of motivational wisdom, suited to their individual needs.

Joan Benoit Samuelson’s career was—is—characterized by a rare combination of ill-timed injuries and longevity, the sum or product of which can only be determination. Benoit Samuelson ran the 2019 Boston Marathon with the aim of coming within 40 minutes of 2:35:15, the time that had netted Benoit Samuelson her first Boston Marathon victory 40 years earlier. She reached that goal with over eleven minutes to spare, running a remarkable 3:04:00 a month before turning 62.

Determination.

Benoit Samuelson didn’t need to hang around competitive running for as long as she has to establish this about herself, but she did anyway. Maybe it was inevitable, like the persistent march of women’s running itself into modernity. I don’t doubt that, despite my unbridled distaste for insincere or self-dealing forms of “social justice,” twenty years from now, we* will all look back on today as a time when much progress in the area of female athlete development needed to be made, as a lot of bad actors, almost all of them male and bumbling along below most people’s radar, remain in need of expulsion from the sport.

As for the way I perceived Benoit Samuelson and the way she described herself—her training and her competitive mindset—maybe it’s her droll Mainer style, but she always had a kind of “other side” quality to her, as if she couldn’t quite tell you why she was so great even though she wanted to.

If she wasn’t a true one-of-a-kind, it’s hard to imagine who in today’s ranks, or in future ones, could really be another Joanie. Some of that is because certain firsts can’t be re-achieved, but it’s mostly because of her stamp over such a long period on so many good things, not the least of which was founding the Beach to Beacon 10K. And winning the Falmouth Road Race for the first of six times in 1976, when she was nineteen years old. And…

Nah. There will never be a runner like Joan Benoit Samuelson again.

I prefer to bury this in a footnote, but throughout her Athletics West career, Bob Sevene was reportedly grateful that JBS was training on the East Coast rather than in Oregon with her clubmates. Start reading at page 42 of this document and you’ll quickly learn why. A lot of the events described have been related to me directly by multiple sources over the years, and among oldsters they simply represent sadly common knowledge. The lessons of history are powerful indeed, but unfortunately, many of the eyes and ears of today can’t even learn from the present.