Keira D'Amato, 38, breaks another American record despite sparse training and doggedly goofy Strava punsmanship

The Kooky Tomato of running would be an international threat if East Africa were excavated in toto and launched toward Arcturus

Keiro D’Amato, who set the American record for the 42.195-km road distance in January 2022 with a 2:19:12 at the Houston Marathon despite a remarkably unambitious training regimen, snagged the AR for 21.0975K at the Gold Coast Half-Marathon in Australia on Sunday (1:06:39). D’Amato had ceded the national marathon record to Emily Sisson last October, when Sisson ran 2:18:29 in Chicago. Sisson is the previous holder of the American half-marathon record, having cranked out a 1:06:52 at the Houston Half-Marathon in January.

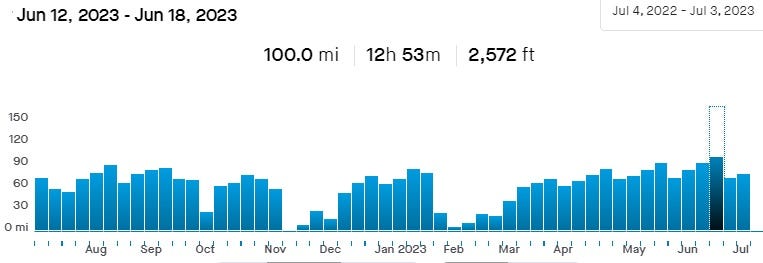

D’Amato, who will be 39 in October, continues to enjoy the usual combination of advancing age, sparse training peppered by inconvenient injuries, and large improvements in performance. According to her Strava profile, she has averaged 8.84 miles per day of training in 2023 (1,627 miles in 184 days). That’s just shy of 62 miles a week, with D’Amato topping 90 miles in only three of the past fifty-two weeks.

D’Amato logged all of 65 miles in February, announcing in mid-March that she was withdrawing from the April 23 London Marathon owing to a knee problem. Yet just three weeks after London unfolded in her stead, D’Amato took second at the Amyway River Bank Run 25K in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which was the 2023 U.S.A. Road Running Championships for a distance no one fast ever runs outside of an annual mid-May race in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

On June 10, a little over three weeks ago, D’Amato was fifth at the Mastercard New York Mini 10K in 31:23, just six seconds slower than her best 6.21371192237-miler on asphalt. The course couldn’t have been slow, as Senbere Teferi’s 30:12 was the fastest 10K ever recorded on American pavement.

In running 1:06:39, D’Amato cleaved a minute and sixteen seconds from her previous 21.0975-km best, which was a 1:07:55 in South Carolina six weeks before her 2:19:12. But despite the sizable personal best, all D’Amato really did was bring her half-marathon time more closely in line with her marathon time.

D’Amato’s best time in a 5K road race is 15:08, a little under 4:53 per mile. 31:23 for 10K is 5:03 per mile. 1:06:39 for a half is right on 5:05 pace, and translates to back-to-back 10Ks in 31:35 plus three and a half more minutes at that speed. The woman finds a way to not slow down appreciably with increasing distance despite having the reverse of the expected training profile for such an athlete, with or without the age factor. Most runners who truly shine only at distances of 10 miles and above are grinders putting in well over 100 miles a week with long tempo runs that scale with their race times.

One argument in support of D’Amato doing what she does without undisclosed and non-disclosable aid is that she makes the most of her minimal mileage by doing a high fraction of it at high intensity. That argument fails on its face for the simple reason that no world-class distance runners are known to have successfully tried this. But it also fails for empirical reasons: D’Amato posts her training to Strava, offering dispositive evidence to the “super-efficient training” thesis.

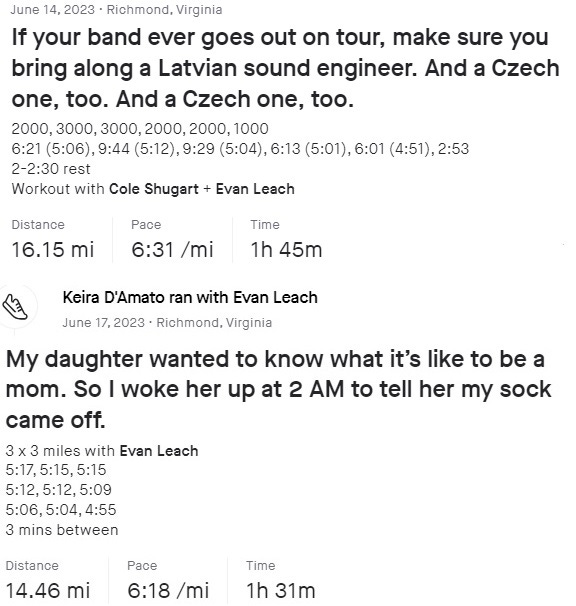

D’Amato does hard, regular, sensible workouts in which she invariably runs faster as the workout progresses. In general, her training seems to follow the “Norwegian method” popularized, or revitalized, last year by Marius Bakken—lots of running close to but ideally not faster than lactate-threshold pace, a minimal amount of truly fast (i.e., 3K pace and below) running, and easy recovery mileage as filler.

But as far as making the most of her training time, D’Amato, considering her ability level, just doesn’t do much overall volume at or near threshold pace; in fact, the hard running she does isn’t a particularly high fraction of her (low) total mileage. Her long runs appear to be easy, 6:40 pace or slower. On her easy days, she putters around at 7:15 to 7:30 pace. I can’t see her doing two lactate-threshold workouts on the same day.

Another argument in favor of D’Amato doing all of this The Right Way is that she is simply an unusual talent, perhaps someone who could be running 1:05 and 2:16 if she trained like most East Africans do. After all, she was absent from the elite scene between the time she graduated from American University and 2020, when she took her personal bests at what are now her best distances from her 2019 marks of 2:34:55 and 1:13:32 down to 2:22:56 and 1:10:01. Maybe she was a latent world-record-setter all along.

That doesn’t work, either. In high school, D’Amato ran all four years and graduated with personal bests of 4:51.9 for 1,600 meters and 10:30.8 for 3,200 meters, missing a trip to the 2001 Foot Locker National Finals by one place. She also ran all four years in college and was a multi-time All-American. But her best times were only 4:42 for the mile, 9:31 for 3,000 meters, and 16:09 for 5,000 meters.

The important aspect isn’t that those times aren’t objectively fast, especially given that D’Amato remained healthy throughout her collegiate career; it’s that this slate of performances is not indicative of someone destined to specifically excel at long distances. D’Amato even fancied herself a mid-distance type at the time, telling Runner’s World on the cusp of her senior-year NCAA Mid-Atlantic Regional Cross-Country Championship, “A lot of people say it’s a miler's course, so it helps out that I have some leg speed” in reference to the Lehigh University course.

Sisson reports running between 110 and 115 miles per week when training for a marathon, typical of those at the sub-2:20 level. D’Amato’s studious four-week mesocycles incorporate at most a total of around 340 miles. She truly is a marvel, and would be one even were closing in on 29 instead of 39. She’s a genuine phenomenon.

I maintain that there are two keys to this puzzle. One is that D’Amato was already a 2:22:56 marathon runner when she signed with Nike in February 2021, with an established and apparently successful career selling real estate. Maybe the money Nike offered was the major convincer, but I think whatever contract talks were held somehow conveyed the idea that a pro contract would come with certain protections and assurances not even an unattached, financially secure 2:20 marathoner could secure independently. She was probably already on PEDs during her bender of fast covid-year times, and unless someone in the mix pisses off the wrong people involved, D’Amato stands no more chance of being suspended for testing positive than any other American superstar.

Finally, another common defense against doping suspicions is “His coach is a stand-up guy” or “Her coach would never stand for that.” This makes at least two seriously flawed assumptions, the chief one being that athletes and coaches don’t often communicate every last thing they do to each other even in athlete-coach relationships portrayed as maximally tight-knit. If you were coaching a world-class runner who seemed to be making startling progress, wouldn’t you just quietly (or openly) attribute all of this to your own wisdom, perhaps even believing yourself at most points along the mental journey?

All of this is somewhat moot, because while D’Amato has done incredible things by domestic standards, rooting for American marathoners is kind of like pulling for the national basketball teams fielded by Great Britain. D’Amato’s 1:06:39 ranks her 20th in the world in 2023, with eighteen of the runners ahead of her being from either Kenya or Ethiopia (Eilish McColgan’s 1:05:43 in April in Berlin is the U.K record and missed Konstance Klosterhalfen’s European and white-chick record from December by two seconds). Her all-time standing in the event is a tie for 82nd place, with a startling 78 of the 81 runners ahead of her being natives of East Africa.

In the marathon, D’Amato stands tied for 45th all-time. Ahead of her are Paula Radcliffe of Great Britain (2:15:23), Sisson, and 42 runners born in either Ethiopia or Kenya. If any Americans running long road events are doping, who cares? They’re laggards on their best days. Between everyone else’s unchallenged or seldom-challenged doping and their superior talent, top Americans need to cut corners just to not fall off the first page of every all-time World Athletics performance list.

Of course, strange things can happen at global-championship marathons. But cheering on characters who are both suspicious and not doing anything on a world stage seems like a waste of fandom, inasmuch as paying close attention to other people’s hyperjogging is remotely forgivable anyway.

Bonus content: Alison Wade’s 2003 interview of Keira Carlstrom (now Keira D’Amato) for the New York Road Runners version of Fast-Women.

The most interesting quote: “During cross country, I was doing between 70 and 80 miles a week. Surprisingly, it never felt like I was doing a lot of miles though.” It still doesn’t feel like she’s doing a lot of miles though. But she seems just as chipper and chirpy now as she comes across in this story, so I think we* can all relax with the unfounded speculation.

Also, it says something grim about both Wade and myself that we’re both still following this shit, though our tendency to work together on projects seems to have inexplicably ebbed over the past twenty years.