More evidence that the subset of trail runners raised in McMansions and subdivisions are among the most annoying human beings alive

"I AM UNFOLLOWING YOU" is the cry of snowflakes deprived of blocking, muting, or otherwise escaping discomfort—even as they willingly submerge themselves in the most triggering Internet filth on offer

In my frequent and sweeping potshots at trail runners, I have been languid at best at emphasizing that I am targeting only a small but noisy fraction of people who run long distance and prefer to do so on natural surfaces, typically with lots of climbing and descending involved. While these people have hijacked what’s left of Outside’s slate of publications and prefer to live within at most five miles of where I do, their insistence on standing out in any normal crowd as emotionally stunted and hysterical simps makes them easy to distinguish from normies wherever they happen to roost.

When I was regularly running 100 or more miles a week, I did as little of this as possible on asphalt roads. I had access to boonies, and to me, dirt roads with little to no traffic are almost indistinguishable from trails. Today I have to be careful to avoid too much descending lest the knee-cartilage issue I suffered six years ago resurface, so I rarely make use of the trails west and southwest of Boulder proper. Those trails are also laden with Karen types lost in their phones as they shuffle along, not noticing any snappy or snorty mayhem their loose dogs may be inflicting. At least until one climbs above 6,250’ elevation or so.

When I lived in New Hampshire, I went long periods running probably 50 miles a week in the Mast Yard State Forest, usually with my yellow Lab Komen and sometimes with a few of the high-school kids I was coaching. I also ran on snowmobile trails when these were snowless, and in late fall, I would often encounter hunters. Anyone intimately familiar with New Hampshire knows that I am among the sixteen Granite State natives since the 1780s to never apply for a hunting or fishing permit.

Hunting game is something I have no foundational moral opposition to other people doing. As someone who eats meat, this would be incoherent. But I could never shoot an animal myself unless my life was in danger—that is, unless the animal was preparing to harm me, or I was starving. This includes human animals.

I grew up in the southern part of the state, more or less at the northern tip of what the U.S. Census Bureau considers the extended Boston metropolitan area. But I lived among many woodchuck people. My best friend in junior-high school was a kid named John whose father grew up in backwoods Kentucky as one of something like fourteen siblings, and this kid was introduced to guns at an early age. Mostly shotguns. One time, John and I decided we would make a slapstick version of a pipe bomb using metal from my grandfather’s wind-chime stock, a glue gun, a length of candle wick, a power drill, and a small pile of black powder from the limitless supply in John’s garage. Little did we know that this was actually no watered-down version of an explosive. It was a legitimate working pipe bomb, and all I will say is that we were very lucky no one was hurt when it may have been lit inside a long-unused doghouse at the far end of a truculent area resident’s property c. 1987.

But John was very responsible around firearms even as a preteen, even though he also occasionally liked to use cans of WD-40 to create makeshift flamethrowers, just to liven up the summertime lull between neighborhood wiffleball games. In the winter, we would don snowmobile suits and goggles and stage BB-gun wars while riding snowmobiles, pretending we were Finnish World War II soldiers (who may in reality have gotten around on skis). We had a strict one-pump rule that no one abided by, especially after getting tagged with a small ball-bearing right between the shoulder blades, because, protective layers notwithstanding, this tended to sting and command a strong vengeance-seeking urge.

John later went on to enjoy a long and fulfilling career in law enforcement. I shot an M-16 and an M-50 at some dummy targets in the Army whenever I was asked to, and for the most part I keep guns out of my hands these days, unless I feel like holding one and lovingly caressing the shined-to-perfection barrel like it’s alive and responsive to touch, wondering if I should get around to filing off the rest of the serial number in case the weapon has finally been reported stolen.

All of which implies that I’ve long been used to seeing and being around hunters, most often while running in late fall. (The sight of someone “hunting” big game in the spring or summer, or at any time after dark, is always a different story and generally serves as a warning to avoid whatever drunkards are plying their ignoble jack-lighting trade.) While I never liked encountering hunters while in a groove, and the need to briefly stop just to make sure everyone around knew who among the gathered was both four-legged and shootable and who wasn’t, I always understood they had a right to be out there and were a fixed element in the landscape. And hunters tend to forge enviably strong bonds with their dogs, which are always fit and stately.

It also helped that I noticed that hunters as a rule are almost manically diligent about cleaning up after themselves, more so than most if not all others who use the outdoors. In New Hampshire, I was always far more likely to see a discarded Gu packet on the ground on a trail popular among both formal exercisers and hunters than a discarded tin of Copenhagen snuff.

Hunters will tell you they respect the woods. Some people somehow find this hard to believe because of the whole animal-killing thing, but a lot of these hunters essentially grew up in the woods. I bet Hawks did. The only reason these constitutive wanderers and angle-seekers and duck-blind-builders even put cabins and beds in their patches of woods is because the weather sometimes sucks, a need for sleep is inevitable, and you have to mount the heads of those magnificent eleven-point bucks somewhere.

Of course they respect the woods. They have nowhere else to go, and they’ve rarely ventured anywhere else without a compelling reason.

I do not presently know anyone who only eats meat they obtain from hunting. But I used to know a half-dozen. Trust me, these people are out there and you can feed a typical family for a long time on a single significant moose kill (hunters with foresight tend to own large freezers).

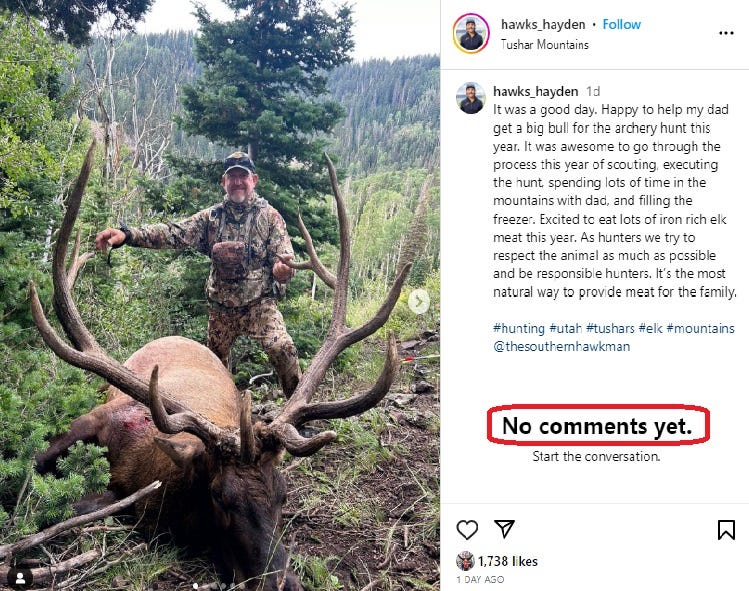

Or an elk kill. The image below appeared on Friday on the Instagram account of Hayden Hawks, an elite ultramarathon runner (anyone who wins the JFK 50-Miler even once, as Hawks did in 2020 while averaging 6:22.4 per mile, earns that designation). The photo is of Hawks’ father and an unidentified elk.

I can see why some people didn’t want to see this. While the caption Hawks added should have been sufficient to convey what the day meant to him—time with his dad, a plan coming to fruition, and an assured supply of the most absorbable form of iron any food contains, at last notice an important consideration for participants in aerobic activities—the dead, defeated-looking animal in the foreground is simply an unpleasant tableau. It might be easy for a random interloper to assume that the man behind the animal was gloating in an “I won!” way.

I saw a few comments along these lines: “While I get it, this makes me sad.” I also wish humans didn’t have to eat things that were once alive to stay alive, and some of the reminders can be stark. But that’s the way the game is played.

I’m guessing Hawks anticipated that his post would receive plenty of blowback, and that he would not have posted the photo his account of the day and this capturing of its essence didn’t mean enough to him to offset the guaranteed flaming. Posting photos that capture personally meaningful moments is exactly what normal people, although sparse on the Internet these days, use Instagram accounts for. Social-media influencers and their dimbulb, ADHD-charged fans are playing a different game, an openly sordid and insecurity-driven one, and would have to work very hard to understand that normal people do not share their perspective on Internet grief-reduction.

Now, the majority of the comments were positive. The post now has over 1.750 likes. But there were no fence-sitters in this crowd. Those who were unhappy made their feelings clear, and many of them decided to go thermonuclear on Hawks: They announced they would no longer follow him.

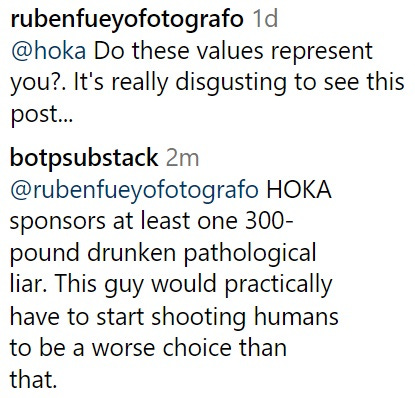

There were a few angry comments that were not punctuated by cries of “so we’re getting a divorce, you cad!” But the above image includes only contributions that contained an explicit declaration of independence from the Insta account of Hayden Hawks, except for one especially acidic one that just made me laugh.

Hawks is evidently sponsored by HOKA, leading one guy—who seems to spend his time flying all over the world to take photos of races he doesn’t compete in—to play hall monitor on Hawks.

I don’t think that the tattle-tale ever saw that response, an obvious reference to Latoya Shauntay Snell, because by late Saturday night, there were no comments or responses to comments to behold.

You can tell which trail runners here grew up using, learning, and appreciating all aspects of the woods, and which segment grew up in McMansions in subdivisions and later discovered trails as part of self-actualization quests—almost all of them meat-eaters and the rest typically looking half-dead.

I can understand why some people dislike this photo, and I can half-accept that some people feel the need to unfollow this account (even though all of Instagram is a cesspool rife with literal child molesters—after all, it’s Meta), and to my knowledge no one is forced to visit the site at all. So why not just quietly unfollow the account, rather than sling a handful of weasel-dung at it as you bravely flounce away having gotten in the vital Last Word?

That’s easy. While people do exist who silently opt to not follow certain social-media accounts, the ones who announce their departures aren’t really shouting at the offending account-owner. They’re shouting at each other. This is one more painfully stupid and transparent episode of virtue-signaling at 150 miles an hour.

Anyone who announces "I'm unfollowing you" has no idea how pathetic and feeble, albeit hilarious, he or she appears to normies, and they never will because these are the same kinds of people whose first and never-denied impulse when confronted with something online they instinctively abhor is to mute, ban, or block it. Especially if it’s true. Don’t examine it; just get rid of it. This is how people like Zoe Rom and David Roche are able to remain magnificently stupid despite being routinely invited to learn things. They don’t need facts when they have followers—dumb ones who will give them money in return for crude ego-management.

Although all of these people should strongly consider promptly getting the hell over their gelatinous, hypocritical selves, they all just did Hudson Hawks a favor. Because of the nature of online trail-running communities and his standing in the sport, Hawks will always have irritating harpies looking at his posts and trying to coerce him into conformity. If he takes care to never go too long between posts like Friday’s, any irritating types who have started following him will naturally disappear. He won’t have to worry about snarky commenters because they'll cancel themselves in droves without express invitations to sod off.