Ron Clarke is among the few all-time great 5K and 10K runners who would still be competitive in 2023

This was supposed to be a sport sufficiently basic to resist significant transformation by technological factors. That proved untrue, so let the speculation begin

Ron Clarke was an Australian long-distance runner who set at least 17 world records and as many as 19 if en-route performances are counted (a sketchier proposition before fully automatic timing became the norm). His ascendancy and prime years overlapped with high fidelity with those of The Beatles.

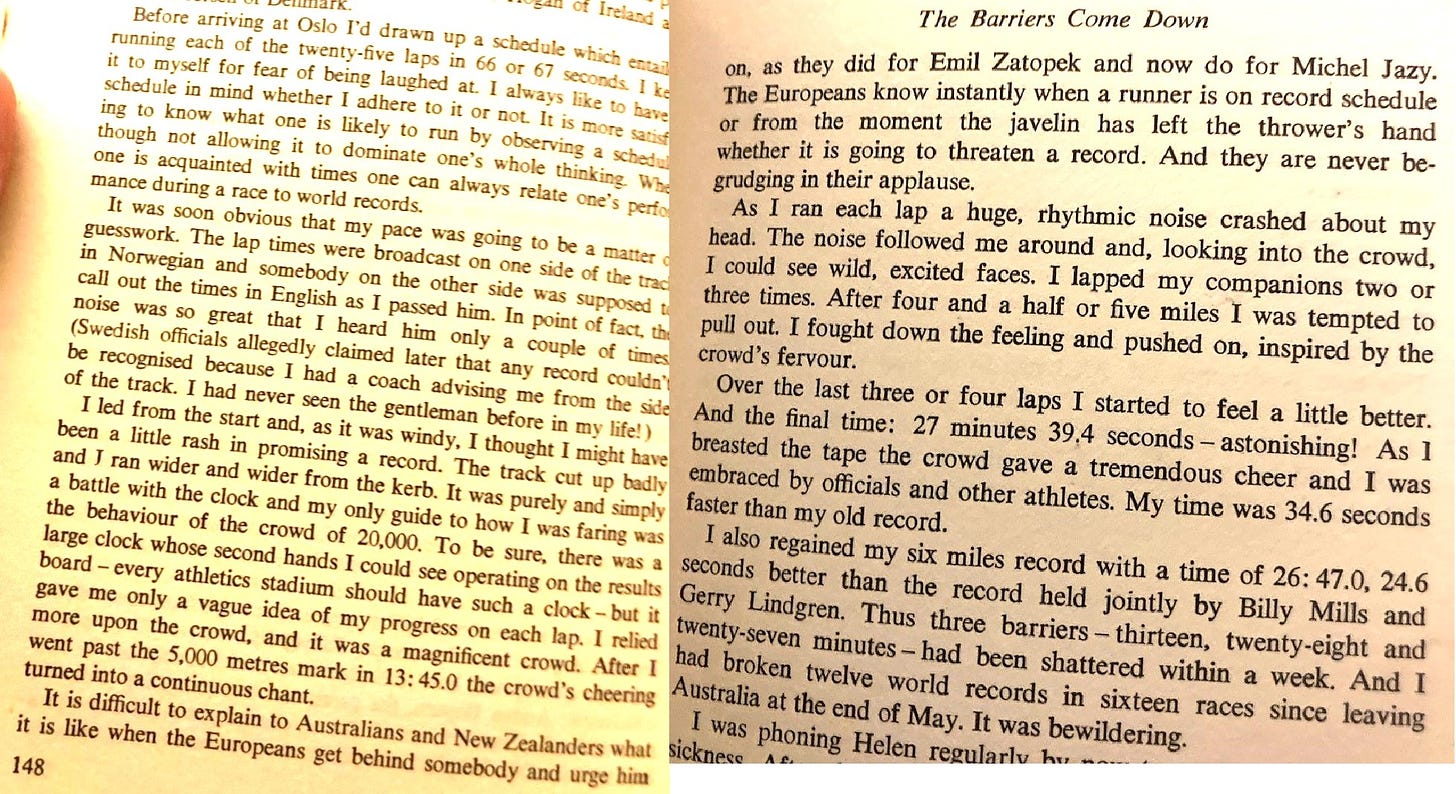

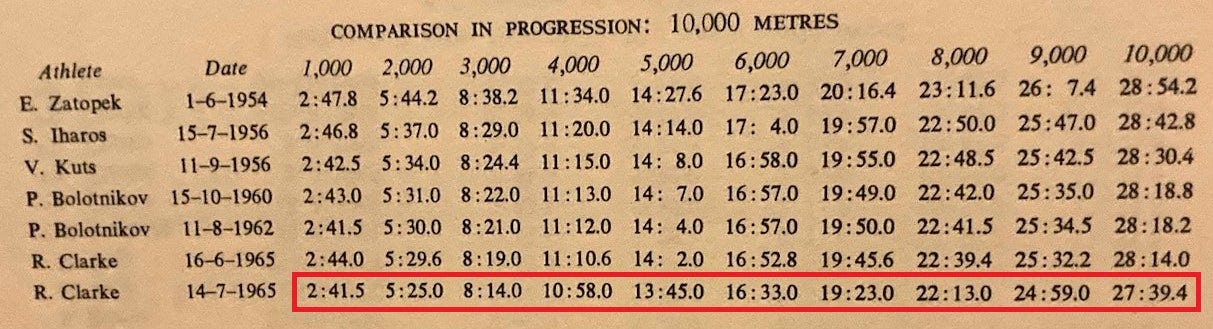

In 1965 and 1966 in particular, Clarke, who died in 2015, was a prolific and close to unstoppable racer. Perhaps the highest-quality performance he ever turned in was a 10,000 meters on July 14, 1965 at the Bislett Games in Oslo, a race that almost didn’t happen for lack of runners interested in running 25 laps in Norway that day.

Clarke held the world record going into the race: 28:15.6, set in December 1963 in Melbourne. Clarke crossed the line in Oslo in a time of 27:39.89, lopping over 25 seconds—1.4 full seconds per lap—from his nineteen-month-old standard. This was in effect a solo time trial, as detailed in an excellent write-up by Len Johnson for Runner’s Tribe last month, “Ron Clarke’s Greatest Week?”

Look at the track that served as substrate for Clarke’s 27:39.

I’m guessing about 80 percent of current or one-time competitive runners reading this have never set eyes on a dirt or cinder track, let alone run or raced on one. There were still a few of these scattered around New Hampshire when I was in high school in the late 1980s; D-II Laconia High School had one, D-I Portsmouth had one, and in my hometown of Concord, even Saint Paul’s School—a prep school that lists William Randolph Hearst, Cornelius Vanderbilt III, J.P. Morgan Jr., William Howard Taft IV, Robert Mueller, John Kerry, and one of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s sons as alumni, and even then boasted an annual operating budget of about $4.7 billion and an endowment fund of around $15.8 trillion—had not only a cinder track but a dismal one shaped like a rectangle.1

I have no way to know how much slower these cinder tracks were than ordinary tracks of the day—most of which were asphalt—or Mondo tracks, or whatever they’re using today. For the faster kids, it seemed like around a second per lap, but this is also a very easy number for the mind to settle on absent proper logical justification.

I do know that Clarke did not have access to the following niceties and perks available to 5,000-meter and 10,000-meter runners today, including:

Modern track surfaces

Formal pacesetters

Pacing lights

Modern racing shoes

Erythropoetin, human growth hormone, steroids, steroid precursors and analogues, peptide injections, plasma-volume expanders, L-carnitine- and thyroxine-based metabolic management…

The 10,000-meter world record today is 26:11.00, held by Joshua Cheptegei, who on Sunday won his third straight World Championship title in that event. Seventy-one runners in all have broken 27:00, with Americans Galen Rupp (#19 all-time, 26:44.36) and Chris Solinsky (#68 all-time, 26:59.60) the only two of these not born in Africa. Jack Rayner holds the Australian record with a 27:15.35 from March 2022.

In comparing the Clarke to whom the world was treated to the Clarke who might have been, different observers will assign different amounts of weight to each of the above factors, using a non-doped athlete on cinders as a baseline. I’ll take each of these factors in turn.

I can plausibly “improve” Clarke’s time from 27:39 to 27:15 by substituting an asphalt track for a cinder version, and work it down to around 27:05 by further substituting an ultramodern one.

Pacesetters and pacing lights would not have helped Clarke run any “harder”; he was Australian, for Chrissakes. But these add-ons might have helped him avoid overzealous starts. I don’t have a copy of The Unforgiving Minute with me, but I’m almost certain that it reports Clarke going out in 63 seconds in his 27:39—about 26:15 pace. It seems likely that Clarke could have tracked someone or something moving evenly around the track at 64.5 seconds a circuit for a whole 10,000 meters, bringing his handicapped 27:39 to the around the 26:55 level.

The benefits of modern racing spikes seem to vary considerably across fast runners. U.S. runner and easily rooted-for individual Ben True has remarked that the shoes alone might be good for a second a lap even at his level (27:14). This seems like too much, at least for the average world-class guy. I’ll assume Clarke could have run close to 26:40, maybe 26:45, in “superspikes” (ideally not Nike’s) in 2023 on the same training he relied on over half a century ago.

Now, because all world-class runners today either start taking drugs soon after committing to being professionals or wisely retire from the sport within a few years, it is fun to imagine a doped-up Ron Clarke, who would have to be capable of keeping up with American record-holder Grant Fisher (26:33.84). But I prefer to truncate the thought exercise without imagining Clarke cheating.

I don’t think any of the steps above are especially permissive—in fact, I’m aiming for parsimony. Just as I believe that Clarke’s contemporary Jim Ryun is the greatest U.S-born miler of all time, I think that Clarke is among the three to five most talented non-African long-distance runners who ever lived. It’s too bad he’s largely known as the man Billy Mills shocked on the last lap of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics 10,000 meters, beating back Clarke to a silver medal, and the guy who suffered so horribly in the high altitude of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics that he didn’t remember running the last lap (he finished sixth).

*** NOTE ADDED AT 8/22/23 9:55 p.m.: Someone with a copy of The Unforgiving Minute sent me some photos clarifying how Clarke ran his 27:39. His kilometer splits ranged between 2:40.4 and 2:50.0, and he was running alone in what he described as windy conditions.

What does Clarke credit most for this incredible effort? The crowd.

My math-team and cross-country comrade-in-legs Chuck loved riding his Wicked Witch of the West-style bike around that track for time while wearing shorts; one day he finally wiped out, winding up with a vicious dark raspberry—a graphite tattoo, really—on one leg from the cinders that I would bet is still there. Macrophages gotta eat, too. What a dumbass.