Running from the Facts: "When all else fails, fart your way around Beaverton" edition

When you've wandered past skepticism and into deep caverns of stupidity, why not keep stumbling even further into darkness?

After the mid-June uproar over Shelby Houlihan’s newly announced, but already well underway, four-year ban from athletics faded into a buzz, some writer out there willing to trade looking like a fool for additional attention was certain to continue pushing the idea that Houlihan’s suspension is—despite how bad the evidence admittedly looks—maybe a mistake, “maybe” meaning probably if not perhaps definitely. And that writer was going to do this by enacting a drama meant to fill in a supposed blank in the Athletics Integrity Unit’s investigation (remember that word) of Houlihan’s positive nandrolone test last December, that being: Could someone on the ground produce a burrito packing ingredients capable of unfairly knocking Houlihan out of the sport?

With a July 7 story in Willamette Week titled “Shelby Houlihan Says a Burrito Ended her Olympic Career. We Set Out to Find It,” Robin Donovan has become that writer. Although she describes herself as a freelance science journalist, the article’s subhead signals just how serious an effort this piece is at “exonerating” Houlihan even in the court of public opinion: “For us non-Olympic hopefuls, pig organ meats are safe to consume. And pretty darn tasty.”

None of my unfavorable reviews here mimic suspense novels, and this one is no different: Donovan (and some unspecified others; the story is written in the first-person plural) didn’t find what they were looking for. Which she knew would be the case, as the glaring omissions in her quest I’ll note below demonstrate.

It’s unclear why anyone believes that Houlihan’s legal team didn’t explore every avenue leading to a possible defense during the many months Houlihan’s lengthy ban was shielded from the public. What else would they have been doing? But apparently a few people do believe as much, perhaps because a few people have millions of microscopic swoosh-shaped fibers embedded in parts of their brains that are supposed to contain only neurons, structures better suited for thinking-related tasks.

Donovan’s opening half-dozen paragraphs or so are background, unhelpful to the “We can show Shelbo got screwed” message, but offering a slapstick aside about the reason for Sha’Carri Richardson’s far more recent drug suspension (“she admitted she had taken some weed to cope with the stress of the trials”). The real fun starts with this:

Houlihan has never named the food truck, and neither her agent, Chris Layne, nor her legal team at Maine-based Global Sports Advocates responded to WW’s requests for comment.

Hold on. Houlihan has a receipt and geodata pertaining to the burrito purchase, but couldn’t or wouldn’t name the truck? Is this new information? Because that looks a lot like someone who threw the rudiments of a standard superficial defense together, only to tap out when a non-fakeable piece of critical evidence inevitably came due.

Emphases in the material below are mine.

We set out to find the burrito, searching for Mexican food trucks in Beaverton and around Nike’s headquarters, where Houlihan trains…

We looked for trucks that serve both burritos with pig organ meats and carne asada, to match Houlihan’s December order, and that seemed authentically Mexican, per Houlihan’s statement. We also searched for burritos that weighed enough to plausibly contain 300 grams of meat—the approximate amount needed for a false positive.

Okay, so these hungry gumshoes fished around town for trucks that “seemed authentically Mexican” (by what standard is unclear) and might have included enough meat to trigger a “false positive.”

First of all, this science journalist needs to learn the difference between a false positive result—one in which a test registers as positive despite the substance of interest not being present—and a positive result that isn’t disputed per se, but whose automatic penalty is being challenged on some “wasn’t my fault” grounds. Given this magnificent confusion of basic principles, it’s not surprising that Donovan fails to mention the level of nandrolone metabolites found in Houlihan’s urine—5 nanograms per milliliter. She therefore frees herself of the need to explain how "approximately” 300 grams of the right kind of meat can lead to so high a nandrolone-metabolite level—two and a half times the permissible World Anti-Doping Association, or WADA, limit—and so she doesn’t. Nowhere in this story is there a link to a journal article or even a Mad Magazine “fold-in” establishing that such a possibility even exists.

Everyone knows the Houlihan case is over, right? And that her testing positive for a banned performance-enhancer did not come as a true surprise to any unbiased and experienced observer of world-class track, even if it came as a disappointment to many? No? Okay, let’s try something else.

Good news for Houlihan: At least three food trucks within a 10-minute drive of Nike match all of those conditions.

Good news for Houlihan how? I’d really like to ask Robin Donavan exactly what was running through her mind when she decided to include that line. Is Shelby Houlihan going to e-mail a link to this story to all relevant sports-governing bodies in the expectation that the article’s mind-blowing contents will be sufficient to overturn all proceedings and findings in her case?

Donovan says that she and her crew managed to obtain burritos weighing 684, 527, and 593 grams. Assuming these values aren’t just guesses, and some kind of measuring equipment was used to produce them, why didn’t Donovan also weigh the meat-only portion of each burrito, i.e., the portion of alleged central interest? Wasn’t there something special about the number 300 here?

I’m not seeing a lot of other science happening, either, especially when you get to the end to find that, while Donovan and her pals ate their fill of odd, greasy stinkflesh and had a good time, she didn’t take any of the meat to a lab that could test it for the presence of nandrolone—a nontrivial detail given the aim of this roving dinner. Nor did she or any of her assistants arrange to take a drug screen ten or so hours after their repasts. Donovan stresses throughout the piece that she tried to replicate as many of Houlihan’s alleged choices and actions from that fateful December day as possible, so why didn’t she do this with the most important stuff?

This recap of a minor al fresco dining adventure of sorts is not a good-faith effort at anything. It ascertains nothing more than the author’s ability to tell, using her standard senses, the differences between regular meat and pig offal, at least when she was already looking for them. Even if Donovan understood the subject better, it’s plain that this was nothing but a field trip to write about for clicks before one more controversial name fades into the dustbin of track infamy.

Erin Strout, who reliably attaches herself to whatever mindless running chatter bobs her way, decided to call the process described in Donovan’s story something it clearly wasn’t:

If someone politely asked Strout what the purpose of the “investigation” was, what it found, and how those findings should be or even could be used at this point, she almost certainly wouldn't answer, because Erin Strout has no time for mean, stupid, uninformed questions. She has her ideas, and being a journalist with a real journalism job, these are by definition good ideas. She may be the smartest utter moron alive.

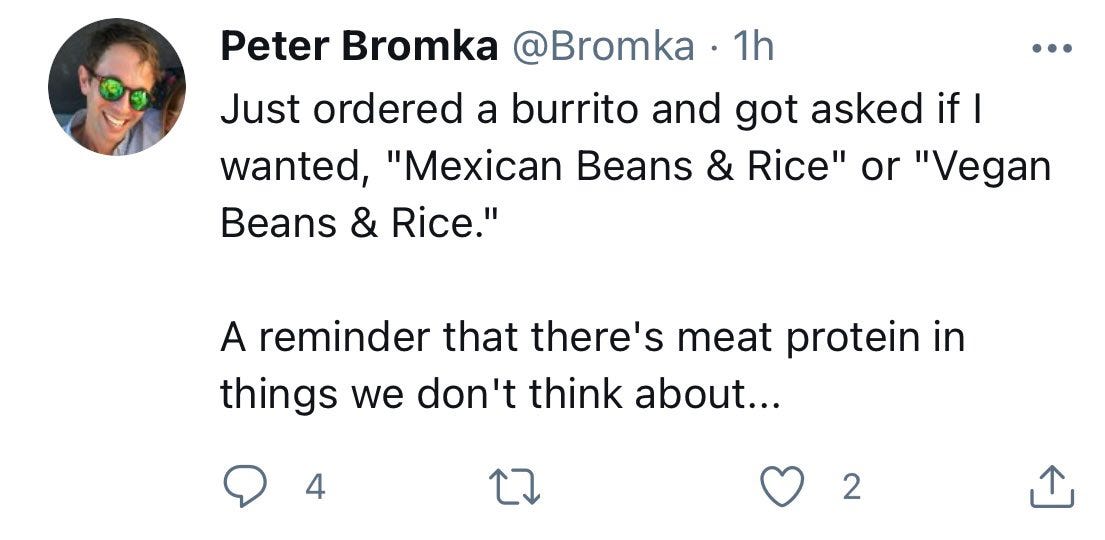

The person she’s crediting for the “hat tip” is Peter Bromka, among the most annoying and hectic of distance running’s ball-washing and jock-sniffing figures. In addition to wanting to overload the Olympic Marathon Trials (he narrowly missed qualifying himself several times in the 2020 cycle), he’s a member of the Bowerman Track Club’s appendage for non-elites, and he takes his role as an imperious, fact-squelching dickhead very seriously.

When the ban was first announced, Bromka tried to shame mountain-runner extraordinaire Joe Gray into silence as if Gray were talking about a mere rumor.

He also sees perfectly objective parties putting in a good word, all to no avail. Why won’t we* listen?

Also, consider the possibilities, people…engage.

It might be a good idea for 2021 Peter Bromka to take advice from 2019 Peter Bromka, who doesn’t like people using Twitter to tell others what to think:

Bromka should feel free to leave Twitter and detach his lips from the anus of the Nike corporation and its elite runners, and hope that in the aftermath, some of his forebrain becomes miraculously regenerated. He needs it; the guy is a supreme jackass. His thumb-sucking delusions about Shelby Houlihan and her sewer-rat teammates are one thing, and he’s welcome to them, but his attempts to squash discussions that make it uncomfortable for him to maintain those delusions are another, and he can shove those up his haplessly posturing ass.

So there it is. I doubt anyone needed help with this particular newslike item, but low-hanging media-fruit is still fruit, even chunks so overripe you can make 150-proof smoothies just by throwing them into a Camelbak, adding a little yeast, and jogging around for a while. And these days, champions of disinformation like Strout and Bromka are always on hand to try to get followers of running drunk on whatever fact-free elixirs they’ve imported—from, say, “freelance science journalists”—when not already busy distributing their own nasty brews.