"Shaking the Tree" is the best song ever written

And too few listeners, even musty ones, seem aware of it

It’s okay to admit to not being a fan of Peter Gabriel or even to disliking his music. You’d be among the few adults I know to hold the first position and among the only people in the world to hold the second, but that’s no reason to sit in a corner wallowing in shame and fuming about whatever the hell is wrong with your brain, specifically your temporal and parietal lobes.

I first gained awareness of Peter Gabriel in 1986, over a decade after he left the band Genesis. That year, Gabriel released his fifth solo album, So. (The curt title was a grudging concession to having to name his individual chunks of studio work at all; his first four, he simply called Peter Gabriel and left it to discographers to sort out the mess.)

So contained the song Gabriel remains best known for, “Sledgehammer.” Rife with intentionally overwrought sexual metaphors, the song was and is incredibly catchy and is impossible to not dance to while driving. The accompanying, painstakingly made…well, mini-movie remains the most-viewed music video in the history of MTV. The song became my anthem for the 1986 cross-country season1, when as a junior I was starting with New Hampshire’s almost-best after being a nonentity to that point. (“Money for Nothing” by Dire Straits had fended off all challengers during the spring of 1986, powering me to a 4:43 1,600 meters and a spot in the slow heat of the state meet.)

“Sledgehammer” is a Hall of Fame song. But it’s not Peter Gabriel’s best song. Not even close, even if you want to award it the silver medal within the formidable Gabriel canon. (“In Your Eyes” gets a lot of people’s votes for Gabriel’s best or second-best song, largely from Gen Xers on the strength of a single scene in the endearing 1989 John Cusack coming-of-slackerhood vehicle Say Anything.)2

In the late summer of 1993, a friend invited me to a Peter Gabriel concert, giving me about four days’ notice and knowing I’d have nothing better or even worse to do on the evening in question other than spank the monkey and run, which sounds kind of like a Steve Miller song. She said the tickets were in hand and already paid for. I already was quite dumb then, but not yet hopeless, so I confirmed the date.

That gave me about a week to prepare. By this time, unaware that the world would soon be ambushed by the grisly bane of grunge rock and its cavalcade of depressed and wailing longhairs, I was treating myself frequently to the uplifting strains of Pink Floyd, The Who, Led Zeppelin, and other bands that had lost at least one founding member to cataclysmic alcohol or psychedelic drug abuse. Plenty of rap, too, but I was suave about it, unlike this guy.

I obtained in this critical period of study a Peter Gabriel collection, on cassette, called Shaking the Tree: Sixteen Golden Greats. This compilation had been released less than three years earlier, in November 1990. Many of the songs I was familiar with. The one in the title, I wasn’t.

“Shaking the Tree,” originally “Shakin’ the Tree,” was originally a 1989 collaboration between Gabriel—then already years into his developing, if not performing, his tragically underappreciated “world music”—and the Senegalese musician Youssou N’Dour. Released in 1989 only as a single, the song was reworked by Gabriel for Shaking the Tree: Sixteen Golden Greats.

I will just blow past the token disclaimer that individual reactions to music vary widely, even as I acknowledge that only a few people will become as instantly enchanted by “Shaking the Tree” as I was, and dare you to not like this song.

Here’s the studio release. It’s six minutes and twenty-four minutes of time you’ll never get back. (Am I using that correctly?)

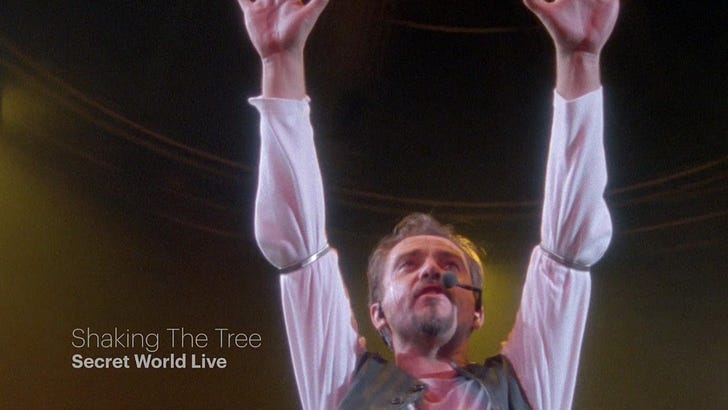

By the time the day of the concert arrived, I must have listened to the song fifty times. I knew I would hear it live, because the concert was a stop on Gabriel’s Secret World Live tour, an orgiastic sonic epiphenomenon unto itself.3

The live version below is from a concert in Modena, Italy, best known for its high rates of Balsamic vinegar trafficking and a locale with a different flavor—I’m just guessing—than Worcester, Massachusetts, ironically among the sourest cities on Earth. But this rendition is much like the one I saw at the Centrum (now the DCU Center, and the city’s only redeeming feature to this day).

Most listeners I’ve unofficially surveyed seem to prefer the live version. I can affirm that watching and listening to Gabriel and his multicultural team play this and every song they performed was an experience I wouldn’t trade for any amount of money today. The music of Peter Gabriel and his string of beatific collaborators has changed my tumultuous life too much for the better to be subjected to the indignity of an estimated price tag.

I’ll try to break the song down structurally in a way likely to confuse people unfamiliar with music while annoying those with a better grasp of the proper in-use terminology.

The studio version is in the key of A major. Almost without a break, the chord progresson is E flat major (one measure), A flat major, D flat major (one half-measure each). It’s in 4:4 time, but the syncopation of the percussion gives the rhythm a “this…that…this…that” feel that’s indispensable to the overall flow—you get sucked right away into notes and beats that sound just a little premature or slightly late.

The live version is in B flat major. I like that key, but I like A flat major better because it’s essentially the same as F minor and that’s the key “Foreplay,” my holy grail of disciplined keyboard playing, is in.

The lyrics are not complicated, although someone who thinks Tony Soprano is still alive probably shouldn’t be trusted to interpret modern performance art. “Shaking the Tree” is part celebration, part exhortation, and part lamentation.

“Souma yergon, sou nou yergon,” which is Senegalese for “If we had known, if we had only known.” As in, “If we (men) had only known that women are more than a breeding resource, maybe the world wouldn’t be a mess of endless wars and resource-hoarding.” Or close. Every other refrain is an invitation to not be held back, to flourish in personhood while embracing womanhood, and so on. It has to be one of the most earnestly feminist songs ever written by men, actually.

But the melody and the percussion make the song. I can’t tell you what instrument is responsible for the bass or the electric strings. But the piano part after the “…we are shaking the tree” makes excellent use of a chord that rolls back and forth between A flat sus4 and A flat major played over the same bass notes—E flat, A flat, D flat. (At least one person out there is trying this.)

The whole production builds to a mini-crescendo at 3:10 (studio version), when there’s a synth walk-down that goes rogue by incorporating a B note. In the live version, this sequence leads into to an extended bridge. In the stuido version, the regular progression resumes, but when the outro starts in earnest, two things happen. One is a brass-synth walk-down from E flat to E flat, with a tantalizing jump up to F. The other is some kind of string instrument that sounds like a koto that, along with Gabriel’s and N’Dour’s vocals and that of the backing singers, carries the rest of the song.

Gabriel again weaves a sus4 construct into the mix using whatever this instrument is, with every measure going E flat major-E flat sus4-E flat 5th-E flat sus4, over and over. It’s very simple to play. I’m intent enough on giving the sus4 chord love to have made this short video, with the patch a Horowitz grand piano.

If you don’t already like this song, I’ve already lost you. I may have anyway. But if I haven’t, see how the song “Rosanna” by Toto uses the same basic trick, but with sus2 chords also included.

The outro reminds me of that of “Hey Jude” (by a group called the Beatles) in that it consumes half the song and seems to go on interminably without getting close to old.

This really is just a triumph of songwriting by one of the most remarkable musicians in rock history. If you come for Gabriel’s humanism, stay for the playful arrangements, the ability to put on a live performance like no one else) before his voice finally went, anyway) and the breadth of his intense stylistic reach.

I’ve always assumed that every high-school athlete assigns an anthem to each competitive season, with duplications permitted but strongly discouraged.

It seems ironic that Cusack, who played the proudly goal-free Lloyd Dobler in Say Anything, went on to have a prolific acting career while Ione Skye, who played his hard-driving, forward-looking valedictorian love interest, fizzled into comparative irrelevance despite being far more fun to look at and listen to than John Cusack, if not Joan Cusack).