The 2023 Bolder Boulder

As the mass race rebounds upward by about 20 percent, the structure of the professional race looks increasingly suspect

Executive summary: The Bolder Boulder experienced a rebound in numbers in 2023, suggesting that large road races may recover fully from the intrusions of covid just in time for the introduction of the next pandemic. But the rebound wasn’t quite what the organizers advertised, as a registration total that supposedly “topped the 40,000 mark” translated into 34,616 official finishers, not counting the 18 male and 15 female pros. That was up about 6,000 over 2022, when the race returned after two years on ice.

American runners won both the men’s and women’s pro races, with Conner Mantz (29:09) and Emily Durgin (33:25) prevailing. But those races need to be revitalized if the idea is to lure any of the world’s best runners to the event; failing that aim, the pro races should be revamped so that they at least don’t suck for the invited runners, as they currently do.

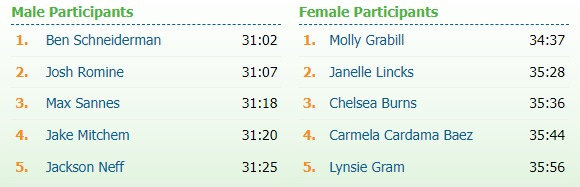

Ben Schneiderman (31:01) and Molly Grabill (34:36) won the men’s and women’s “citizens’” (amateur) races.

The BOLDERBoulder has provided YouTube videos of the “A” wave of the citizens’ race and the pro races, collectively dubbed the International Challenge. Frank Shorter and Alan Culpepper, each of whom represented the United Stares twice at the Summer Olympic Games, do a great job of announcing these.

The Bolder Boulder, a Memorial Day parade instituted in 1979, is America’s second-largest 10K road race. For most runners, the course remains nearly identical to the original; the only difference is that around ten years ago, the starting line was moved a mile to the south. As a result, the first half-mile runs northward along 30th Street from Walnut Street rather than southward along 30th from Iris Avenue before the route heads west along Valmont Road. The new section is as flat as the old one, so the courses can be considered loosely identical, a term right up there with “somewhat unique” on the literary helpfulness scale.

The professional race used to follow the same route as the mass race does, except for a brief, long-ago experiment with a criterium-style course that apparently flopped. A few years ago, the pro starting line was moved to the intersection of Folsom Street and Taft Avenue, right at the bottom of the grim hill the runners climb starting at 9.5K. This move signaled an official abandonment of the idea of luring athletes fast enough to break the men’s and women’s course records, both set in 1995. In what was reportedly a perfect light drizzle, Kenyans Josephat Machuka (27:52) and Delilah Asiago (32:13) turned in performances that proved impossible to match.

Asiago, named the 1995 Road Racer of the Year by Running Times Magazine, would be popped for a doping violation in 1999, serve a two-year suspension, and return to win the 2006 Dubai Marathon. That’s some cheese for ya. But sadly, Asiago is now struggling to survive.

Machuka, meanwhile, was a splendid runner for his era (13:04/27:10/2:07:27) but ended his career best known for punching Haile Gebrselassie in the back of the head in retaliation for Geb outkicking him to win the 10,000 meters at the 1992 World Junior Athletics Championships in South Korea.

Machuka, Asiago, and every other Kenyan making waves on the U.S. circuit in the mid-1990s—when EPO had been available for years, but also years before a direct test for its exogenous administration would be developed—were clearly juiced to the max. Nevertheless, that 27:52 remains one of the most remarkable road runs of all time.

The standard altitude adjustment at 5,300’ to 5,400’ for a race lasting 30 or more minutes is 3.6 percent. If you convert 27:52 into seconds, divide by 1.036, and convert the result back to minutes and seconds, you get 26:54.

The road 10K world record in May 1995 was 27:34, shared by Gebrselassie and William Segei, who in 1994 set the world record for 10,000 meters (26:52.23). To this day, no one—supershoes, doping and all—has run faster than 27:08 on any 10K road course in the United States.

Simply put, Machuka’s run should have been impossible on the Bolder Boulder layout.

I’ve raced on far harder road courses; the now-dead Bridge of Flowers 10K in Massachusetts, for example, made the Bolder Boulder course look like a slightly rippled, badly wandering asphalt track. But it’s a positive-elevation course and a grind. Most of the miles are slightly uphill. There are really only two downhill sections available for regrouping. And if you falter, an endless train of bodies immediately starts huffin’ and chuggin’ on by, whether you’re running 5:30 per mile or 8:30 per mile.

(I experienced this faltering in both my 2017 and 2018 Bolder Boulders. I ran horribly the first time, yet took third in my age “group” (M47) and even worse the second time, in the process moving up to second in my age “group” [guess which one]. Come 2019, I didn’t have the stomach to lace ‘em up again, run an even slower time, and risk winning the M49 category with a time over 40:00.)

Some altitude-born runners simply don’t suffer as much in high-elevation events as normalization charts imply they should. Boulder-born Lize Brittin ran 35:04 for 10K as a teenager at the Denver Zoo Run in the 1980s, when that was practically an elite road time for females, period; the typical runner capable of matching her at sea level would have been a minute behind her in the Mile High City. And she’s not the only native around who gets away with exactly that kind of crap. (The downside for these magical oxygen-conservers is inevitably “underperforming” at sea level.)

Still. 27:52?

Conner Mantz has run 27:25 twice on the track, so he was 6.3 percent slower in winning the Bolder Boulder. Emily Durgin’s 33:25 (5:26 per mile) was 5.9 percent slower than her track best of 31:33, but she has also run 1:07:54 for a half-marathon (5:11 per mile).

Women’s citizens’-race champ Molly Grabill ran 5:16 pace for 10 miles in April, then 5:35 pace for 10K at the Bolder Boulder. Some of that slippage, however, may be owed to the 2:23:18 2:32:18 GOD DAMMIT marathon she ran in Hamburg, Germany five weeks before Memorial Day. Grabill is probably a 2:27-2:28 marathoner-in-waiting.

The male citizens’ race winner, Ben Schneiderman, knocked out a 2:16:22 at the California International Marathon in December. Though that course is somewhat aided, that means Schneiderman only picked up about 12 or 13 seconds a mile in cutting over 75 percent from the race distance. And remember Jarrod Ottman? His CIM-vs.-BB10K pace gap was even narrower (2:16:31 = 5:12 pace; 31:33 = 5:05 pace).

The course isn’t a killer. It’s worse; it’s a gradually numbing pain in the ass.

Also, I couldn’t help but notice that the name of the fifth-place woman in the citizens’ race is a homophone of the name of a sitting U.S. senator. The only thing I can see the two of them having in common otherwise is that one is likely to try to steal the other’s boyfriend, given the means, motive, and oral opportunity.

In my write-up of last year’s race, I reviewed the reasons the Bolder Boulder sucks for the elites: The races start at around 11:30 and 11:40, when it’s normally hot, and the fields are far too small for a loop 10K. The elites have a hard time warming up properly with all the human bodies from the mass race—runners, spectators, stoned trombone players on electric skateboards with stoned dogs barreling alongside—clogging Folsom Street.

Since there is no longer any shot at anyone running a course record anyone gives a stinky-rip about, there is no reason to send fields of fewer than 20 runners off on a single-loop course so they can spread out and suffer for the better part of a half hour alone or practically so. Multiple winners of the citizens’ race have wound up being subsequently invited to the pro race; this almost always goes south, because a 31:00 man or a 34:30 woman running against athletes who can run two minutes faster has little choice but to either hang with too fast an early pace or look like an early quitter for merely running an appropriate pace and dropping off the “pack” at the crack of the starter’s gun.

The organizers could redo the professional arm of the Bolder Boulder so that the elite course makes a few 2K loops through the neighborhoods near Folsom Field, where the finish line is, before climbing up that grim hill leading to the stadium entrance.

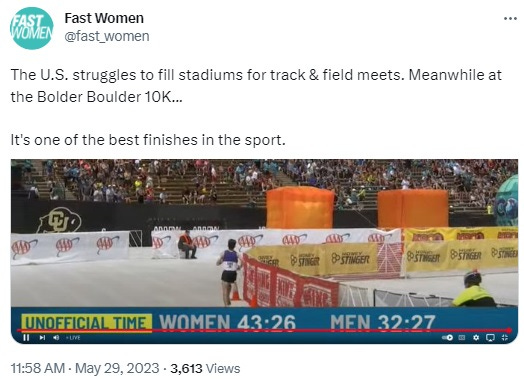

Better yet, they could and should dump the 11:30 a.m. start and run the pros at the front of the citizens’ “A” wave at 7 a.m. There would be no shortage of yammering running geeks waiting at the finish line, many of them still drunk on libations consumed the previous evening. Instead, the race relies on the swarm of people from the mass race milling about the finish area and in the stands all morning to create the idea that thousands of people are on hand specifically to watch the pros finish, when in fact almost none of these participants or their friends even care.

Boo.

(BALEFUL, SELECTIVELY MISOGYNISTIC SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL APPEARS BELOW THIS LINE)

Among the people harboring this mistaken impression is Alison Wade, who operates Fast Women, an anti-woman outfit branded as a feminist enterprise.

I doubt that Wade has ever witnessed a Bolder Boulder finish in person. But either way, when was it ever customary for American stadiums to be packed with spectators for track and field meets? Never. And, although Wade can’t see this for obvious reasons, when someone like Alison Wade is judged to be sufficiently visible and competent for Nike to invite to a Bowerman Track Club “Shelby didn’t dope” Zoom propaganda session, then both the sport’s principals and its media are a sick joke.

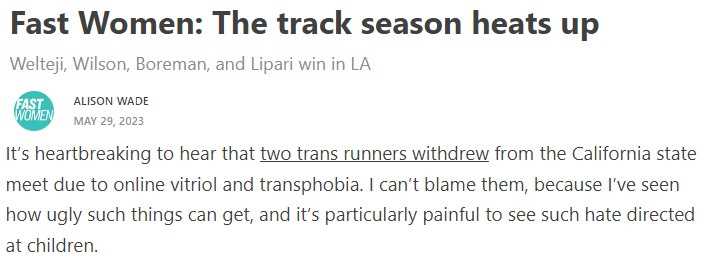

The latest dispatch from this thundering windbag includes this snippet:

Wade is deeply concerned about the mental health of boys invading girls’ races, and thinks kids shouldn’t be pestered by adults.

Is this you too, dickhead?

When boys get the boot or merely withdraw from girls’ races, it’s a tragedy; when girls complain about boys being in their races, it’s “play the hand you’re dealt.” From a feminist.

Wade is playing the hand she was dealt, which is being envious of hotter and faster women and too privileged to grasp that the reason people disagree with her isn’t because they’re behind the times, but because she’s simply a goof who trolls the sport of running as a means of enacting a personal psychodrama.

But I have to credit her grifting skills. Although she’s now on Substack, she continues to receive sponsorship support from companies like New Balance. And this will keep happening for as long as Wade keeps churning out her trash, because these companies are aware that, while Wade is a destructive doofus, if they stopped handing her money, she and her sizable contingent of harridan followers would bitch and bitch about the only dedicated women’s distance-running newsletter being ignored by the industry, and these companies would be buried in the e-complaint version of an endless fusillade of used tampons.

The industry sucks. Going forward, I’ll probably find a way to cover competitive running even in the summer without dedicating much attention to whatever the pros are up to. It’s not the sport’s fault that it’s one more subculture that’s been turned into a compost-heap by liars, dopers, whiners, narcissists, scammers, illiterates, cowards, racists, man-bashers, thieves, slobs, slugs, and purple-haired biology-deniers, occasionally all in one catastrophic, blithering package.

And it’s hardly consoling that this is what DEI/ESG mandates from the child-molesters and mRNA-armed virus-breeders running the world invariably do to all subcultures: They draw out the worst in everyone already present while attracting the looniest possible interlopers to put the final touches on the ruin. By design.

Most people hate this crap, and luckily, there is plenty else out there worth writing about, whether of historical or developing interest, locally and beyond.