The Chicago results highlight how problematic the Olympic Marathon qualifying standard is for American men

Worldwide, 2:08:10 for men and 2:26:50 for women are roughly equivalent marks. In the U.S., we need to shut down women's running until fairness is achieved

Kelvin Kiptum Cheruiyot of Kenya, who goes by Kelvin Kiptum and may start demanding to be addressed as Lord Kelvin, broke the world record in the marathon on Sunday with a time of 2 hours and 35 seconds. I predicted that he would run between 2:00:40 and 2:01:00, so I’ll add that fumble to a losing streak that also includes foreseeing U.S. President Joe Biden, Junior just being Joe Biden, Junior by the end of last month (well, I hedged on that one, but still).

It’s fair after three marathon finishes by Kiptum, all wins, to say that he has a trademark style, and he relied on it to become the founding and sole member of the sub-2:01 marathon club: While already running extremely fast about three quarters of the way in, he accelerated away from anyone still around him and wound up negative-splitting both the marathon itself and the second half of the race—both to a remarkable extent given the narrow margin for pacing error at world-record speed.

After reaching halfway in 1:00:48 (4:38.3 per mile pace) having already left every official entrant far in arrears other than compatriot Daniel Mateiko—who for all practical purposes was Kiptum’s domestique—Kiptum ran 4:39.0 pace for the next 8.9K to being the pair to 30K in 1:26:31. This put Kiptum 2:01:41 pace, thirty-two seconds outside the mark he was looking for. It also meant he had averaged 14:25 per 5K to that point.

Kiptum then blasted away alone over the next 5K at 4:27.5 pace (13:51 split), reaching 35K in 1:40:22 and suddenly on pace to run 2:01 on the nose. He barely slowed the rest of the way, running the next 5K in 14:01 (4:30.7 pace) and then “coasting” the final 2.2K at 4:32.7 pace. From the 30K point until the finish line 7.58 miles later, Kiptum averaged 4:29.7 per mile, a feat so rattling I have no problem carelessly mixing metric and Imperial units of measure to convey the information.

Kiptum ran the second half of the race in 59:47, sixty-one seconds faster than his opening 21.1K. So far, this is the most evenly split of his three marathon finishes, with his 2:01:53 in Valencia last December lopsided by 83 seconds (1:01:38/1:00:15) and his 2:01:25 in London in April skewed to the tune of 115 seconds (1:01:40/59:45).

This lovely freak of both fortuitous allele combinations and interventional biochemistry seems intent on, or at least capable of, getting closer and closer to one hour for the first half of his races while remaining assured he can run an hour or better for the second half. This probably won’t work if Kiptum tries it in the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris (or at least near Paris, if the city winds up completely incinerated by overzealous critics of Western culture before then). But his overall racing style is perfect for a global-marathon setting, provided he’s solid in the heat.

The real question in everyone’s mind seems to be, is this guy already vastly better at 23 than Eliud Kipchoge ever was? Including on the day Kipchoge leveraged both his previously unobserved fitness level and a systematic diminution of aerodynamic drag to cover 42.195 kilometers in 1:59:40?

A man can only be credited with what he has actually done, and Kiptum hasn’t even been to a global championship yet. But this guy already looks to have supplanted human history’s most celebrated marathon runner in terms of raw output. The only reason to pretend otherwise is Kipchoge’s unusually persistent mystique: Everyone has been worshiping him for so long that it was easy to forget that someone was bound to come along who was even better.

Cry “too soon” all you want. As long as he doesn’t go the Sammy Wanjiru route, Kiptum could be breaking records for the next five or six years. And once Kipchoge hits fifty, he won’t feel like putting in 130-mile weeks just to run a bunch of 2:02-and-change fizzle-fests and lose every race by half a mile.

Elite results of the 2023 Chicago Marathon are here, with searchable results for all runners and wheelchair participants just a click or two beyond.

But we came here to talk about more important things, in fact the most important things on Earth: Americans!

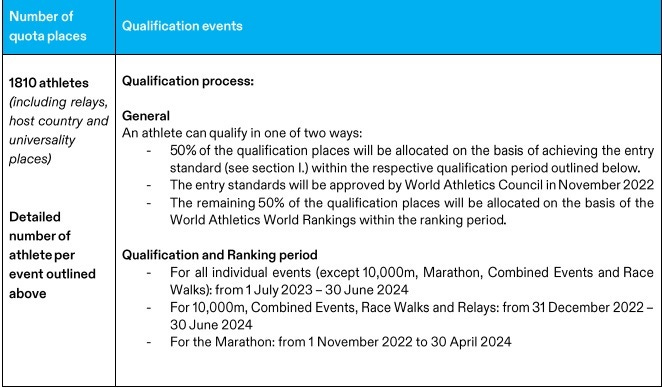

To be eligible for the 2024 Olympic Marathon, men have to run 2:08:10 or faster and women 2:26:50 or faster in a marathon held on or after November 1, 2022 and on or before June 30, 2024.

In Chicago, two American men and seven women reached the required times. This scales nicely with the all-time lists, which show that only six American men—three foreign-born—had ever run 2:08:10 or faster on record-eligible courses before yesterday, while twenty-seven American women (three also foreign-born) had broken 2:26:50.

The women’s Olympic Marathon qualifying time is 14.56 percent slower than the men's. This is greater than the 13.77-percent difference between the men’s (2:18:00) and women’s (2:37:00) qualifying times for the 2024 U.S. Olympic Marathon Team Trials, which will be held in Orlando on February 3, 2024 provided Florida Governor Ron DeSantis doesn’t declare the event to be too gay for his state in the meantime—an outcome that would be foolish to bet against unless the Trials are moved to South Miami Beach.

Chicago NBC 5 posted a story shortly after the race by someone unable to tell the difference between either the 2024 Olympic Marathon and the 2024 U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon or the 2024 U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon and the 2024 U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials. And I don’t think it was the specific year that caused the confusion.

After Kiptum’s 2:00:35 and the 2:11:53 run two weeks ago in Berlin by Tigist Assefa, the difference between the men’s and women’s world records stands at 9.37 percent. Also, on the men’s side, the gap between the world record and the Olympic qualifying standard is 7 minutes, 35 seconds, while the corresponding difference for women is nearly twice as great at 14 minutes, 57 seconds. Since the male-female performance gap closes with each jump in competitive level (e.g., U.S. high school, U.S. collegiate, U.S. professional, East African professional), it would seem that World Athletics could have tightened the women’s Olympic Marathon standard by a solid four minutes if settling on 2:08-low for men.

This idea, however, is not borne out by the current number of Olympic Marathon qualifiers worldwide. With Chicago finishers accounted for, 161 men and 180 women have run the required marks. While this is a statistically significant difference, the practical difference is negligible.

The problem here, especially with Americans having been long established as the best athletes at every sport everywhere, is that the list includes only two U.S. men—both of them graduates of Brigham Young University and therefore probably not recent East African immigrants—but twelve U.S. women (including two born in East Africa). This is not merely a blip, it is a clear safety signal, and anyone who ignores it does so at her peril. I say “she” because all of running’s self-appointed correctors of gender iniquities are women.

We need to fix this, and we don’t have much time, even if June 30, 2024 seems a generations and sixteen mild-to-moderate U.S.-led proxy wars away. The New York City Marathon next month will draw whatever American talent hasn’t been expended yet this fall, and the course is anything but fast. I suppose a few American blokes may travel in December to Valencia, where it seems you can inject yourself with EPO in front of a cafe in broad daylight the same way you can now shoot or smoke fentanyl unmolested in literally any American city with a population of over 100,000 people.

Next year, there are no U.S. marathons besides the Houston Marathon in January that would work other than the Boston Marathon in April, and because that one is run on a downhill course (as well as managed by downward-spiraling personnel), I don’t think it can be used for an Olympic bid unless a runner places high enough among the finishers and qualifies on points rather than on strict time. (I don’t read manuals.) Overseas, there’s always Rotterdam and Amsterdam (formerly the worldwide reference point for the open injection of opioid drugs), but damn if I know many others.

Alas, we not only lack the time to deal sufficiently with this project, but also lack the substrate. A runner has to be in the neighborhood of 27:30 for 10,000 meters on the track to have any chance at a 2:08:10 marathon, and I don’t think the U.S. is hiding any such men, at least not any likely to jump immediately to the marathon. Conner Mantz was able to translate 13:10/27:25 track credentials into a 2:07:47 marathon in Chicago, and that guy is as marathon-centric a competitor as you’ll find.

Also alas, I was kidding about the gender injustice. Maybe the men’s Olympic Marathon qualifying standard is objectively harder, but men outside the U.S. aren’t folding in the face of it.

I often wonder why the performance gap between men and women starts at around 10 percent at the very top, slides to around 11 or 12 percent at the general world-class level, and stands at around 15 to 16 percent at the NCAA and high-school level. I think it is a combination of androgen-doping having both a greater and a far wider range of efficacy in elite women than in elite men and a basic recruitment issue.

I suspect that there are a lot of East African women with the talent to run under 2:20 who will wind up never running a competitive step in their lives. All people, but especially women, don’t have the freedom to choose their own paths in nations like Kenya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Somalia. Sure, plenty of potential sub-2:04 East African men never discover or properly plumb their talent, either, but I’m sure the percentage is far smaller than it is for their female counterparts.

But although the greatest country in history is a roiling, knee-slapping mess at the moment, most of us here do have the freedom to train for and race marathons, or, even better, train for no reason at all and reserve time to yammer ferociously about those who do. And so it was that loose group of 2:23-to-2:25 American women—some of them essentially nobodies even on the U.S. stage before now—put on a display in Chicago that would have short-circuited some noggins only ten years ago even had it come from the likes of Shalane Flanagan, Kara Goucher and Desiree Davila (then Linden, and then obviously faster).

It was actually stirring to watch, probably because even until very recently it was somewhat rare to see an American woman run faster than the marathon than I did (2:24:17, on an “illegal” course, a factor I offset on purpose by stopping at 22 miles to take an “illicit” dump). Some of this is obviously “the shoes,” but there would be far more sub-2:30 American women now than there were in, say, 2008 even without them.

But the 2:23-to-2:25 range just isn’t what it used to be, and it’s at slower end of the Olympic Marathon qualifiers list where most American women’s names are appearing, accounting for the 12-to-2 “lead” they currently have over the men. That said, one of the American women in that range who ran a personal best in Chicago (2:23:07) went into the race as an Olympic medalist, and her personal best before lining up in Tokyo two years ago was 2:27:31 2:25:13. So we can’t cancel our dreams of thumping the Africans just yet, even if the Africans keep making this seem a less and less likely prospect with every big-city marathon.

(10/9/23 Note: This post has been edited to correct to Molly Seidel’s pre-Olympics PR.)