The continuing convergence of the 5K and the 10K at the world-class level

Also, a wet, sloppy kiss blown Tracklnd.com's way

When I started running in the late summer of 1984, these were the men’s outdoor world records in the four longest standard, barrier-free, running-permitted track events, three of which are contested at the Olympic Games and the World Athletics Championships:

1,500m: 3:30.77 — Steve Ovett (GBR)

3,000m: 7:32.1 — Henry Rono (KEN)

5,000m: 13:00.41 — David Moorcroft (GBR)

10,000m: 27:13.81 — Fernando Mamede (POR)

When it came to choking, Mamede had unparalleled resolve; he was a time-trial impresario who reliably performed well only when the chips were up. But that summer, he had taken almost nine seconds off Rono’s six-year-old global 10,000-meter standard of 27:22.47. The other three marks on the short list above were either one or two years old.

Staring at these figures in the winter of my ninth-grade year, I decided that these times were close enough to 3:30, 7:30, 13:00 and 27:18 so that equivalent excellence could be assigned to all of them. Why 27:18? Mainly because it’s exactly 2.1 times 13:00, but also because it’s about midway between 27:13.81 and 27:22.47.

While in college some years later, before the earliest twinkling of the Internet but already in the age of organized book collections, I discovered the Purdy tables, the data from which agreed nicely with my quasi-empirical conversion system. In the process, I also found several charts produced by researchers not named Purdy, each of them differing slightly in their estimation of what, for example, a given 10K time might produce in, say, a similarly fit marathon runner. Because the Purdy charts cohered most closely with my own conclusions, I had no choice but to rule Purdy et al. the most correct of the bunch, and I went on using those tables as a rough personal and coaching guideline for many years. I still do, allowing for individual variations that become evident in each runner over time1.

If 13:00 and 27:18 are precisely equivalent performances, then (10K time) = (2.1)(5K time), meaning that a well-trained runner’s 10K pace is five percent slower than his 5K pace. Or something like that, because this figure—whatever its true value across the population, but let’s say 5 percent is correct for now—is obviously an average with a fairly broad standard deviation. A 5K/10K runner who moves to the marathon with great aplomb will almost always show a smaller percentile pace loss in moving from 5K to 10K than a runner whose best range is 3K to 5K and for whom 10K is already pushing effective range limits.

It is safe to assume that the fastest ten NCAA Division I athletes in the 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters every spring are well on their way to developing as strong an aerobic base as they ever will, at least the fourth- and fifth-year athletes. In this group, then, there is no reason to expect a drastic pace drop-off in the best athletes when comparing their fastest 10,000-meter times to their fastest 5,000-meter times, using the best in the world to decide what “drastic” means. I’m tempted to say that collegiate runners getting only one or two shots a season at a fast 10,000-meter time might tilt the quality at this level toward the 5,000 meters, but I don’t think that’s a significant factor given the presence of the Stanford Invite alone.

In 2011, as far back as TFRRS data goes, the tenth-fastest men’s times in these two events were 13:39.49 (hi, Jake Riley!) and 28:43.30, while the corresponding women’s marks were 15:56.45 (I see you, Aliphine Tuliamuk!) and 33:26.47. These represent pace drop-offs of 5.14 percent for the men and 5.23 percent for the women. That looks Purdy enough.

Last spring, the first outdoor collegiate season of the “superspike” era, the figures of interest were 13:26.74-28:23.60 (5.59 percent) and 15:33.59-32:49.87 (5.50 percent). So, things looked less Purdy at this level in 2021 than they had ten years earlier, contra what I would have expected given the overall increase in quality at this level for both sexes and a greater presumed percentile effect of superspikes on the 10,000 meters.

At the world-class level, as you would expect, the gap is narrower. It’s not unheard of for collegiate distance runners to log 100-mile training weeks in the summer, but at the very top it’s practically obligatory for the 10,000 meters. The older and stronger you become throughout your 20s, the longer the duration you can hold a given hard pace (a corollary of being able to run a fixed distance at a faster pace). Instead of flattening the covid curve, you’re working on flattening the pace vs. race-distance curve, even if you’re not thinking in such terms. And, of course, anything you can introduce into your body that provides a near-immediate bump in the oxygen-carrying capacity of your blood will also act to flatten this curve.

Looking at the World Athletics database and using the 100th-best performances of all time as new comparison points, a 5K-10K pace difference of 4.48 percent exists on the men’s side (Galen Rupp’s 12:58.90 vs. Shadrack Kipkirchir’s 27:07.55) while among women the difference is 4.94 percent (14:44.21 vs. 30:55.83). This hasn’t changed too much for men in the past decade; in 2011, this figure was 4.83 percent, while the corresponding metric for women was the same as it was last year—4.94 percent.

Okay, but what about the very best of the world’s best track runners?

Joshua Cheptegei holds the men’s world records in both events (12:35.36 and 26:11.00). He set them less than two months apart in 2020, the 5,000m record coming first. In averaging 60.43 seconds per lap in the shorter race and 62.84 per circuit in the longer one, Cheptegei managed to keep his 10,000m pace within 3.99 percent of his 5,000m pace. Kenenisa Bekele formerly held both records, and Haile Gebrselassie held them in turn before K-Bek arrived; the 5K-to-10K speed drop-off for these two slightly slower men works out to 4.15 percent and 4.22 percent respectively.

Paula Radcliffe exemplified selective excellence in the marathon. Sure, 14:29.11 and 30:01.03 were solid marks twenty years ago and remain so today, but her marathon running is what set her apart, especially her time of 2:15:25, which she ran in 2003, the year after her 30:01 and the year before her 14:29. That marathon time is only 4.511 times Radcliffe’s 10,000-meter best; if Cheptegei ever manages that, he’ll run no slower than 1:58:07 for the marathon.

Obviously, Radcliffe was an aerobic monster. So, it shouldn’t really be common for anyone who regularly competes at both 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters to slow down less than she did when moving up to 25 laps—3.62 percent.

The world record holder in the women’s 5,000 meters, 10,000 meters, and half-marathon (1:02:52) is Letesenbet Gidey of Ethiopia, a country essentially exempt from doping controls. Gidey must not have gotten into any good 5,000s while fit, because her 14:06.62 and her 29:01.03 have her losing only 2.82 percent of her speed from the shorter to the longer distance. Add that and related data produced by Addis Ababa’s EPO faucet to the fact that Francine Niyonsaba is permitted to compete as a woman, and you get a better idea of why Shelby Houlihan probably wonders what she did to be singled out for sanctioning in a sea of practically obligatory PED use on the distaff side.

On Sunday night, I watched Elise Cranny and Grant Fisher of the Nike Bowerman Track Club chase national 10,000-meter records on a high-school track in California. I was able to view the races live for $5.99 (part of which went to the athlete prize-money pool) thanks to Tracklnd.com, which does an excellent job with these productions.

Beforehand, I tried to estimate Cranny’s chances of lowering Molly Huddle’s 30:13.17 American record from the 2016 Olympics. One half-assed way to go about this was to compute the ratio of her fastest outdoor times in the 5,000m (14:48.01, from 2020) and 10,000m (30:47.42, from 2021) and apply that to her recent indoor 14:33.17 5,000m, after figuring out how to convert that 5,000m time to an outdoor time. I decided that Boston University’s track is so fast2 that, since I was only using half of my ass anyway, I could treat Cranny’s 14:33.17 as an outdoor time. That ratio led to a prediction of 30:16.19, but I didn’t think Cranny would break 30:20 and, because I knew she’d be chasing lights around the track at 72.5 seconds a lap for as long as she could, I believed she would fade to 30:30-ish.

(Huddle, by the way, never ran faster than 14:42.64 for 5,000 meters, although that was also an American record at the time. Her personal-best 5,000m-to-10,000m “pace loss” is even smaller than Gidey’s—2.71 percent.)

In case you missed what did in fact happen, Cranny did everything she could to break Huddle’s record, grudgingly yielding some yardage to the pacing lights starting at around 8K-8.4K and perhaps hoping to make it up in the final circuit, and coming up less than a second and a half short with a 30:14.66. Based on her 14:33.17, Cranny is able to run 10,000 meters at an average speed 3.91 percent slower than her best average 5,000-meter speed. Recall that Cranny graduated from college less than four years ago as a twelve-time All-America selection, but barely broke 15:50 for 5,000 meters after bringing a 4:10.95 1,500m with her to Palo Alto. Stanford and the Pac-12 are tough environments, and apparently no one gets real coaching until moving to the pro ranks and specifically to Portland.

Fisher, for his part, was coming off a 12:53.73 indoor 5,000 meters at Boston University, breaking Rupp’s American record by over seven and a half seconds. The 2019 Stanford graduate had lowered his collegiate 5,000-meter best of 13:29.52 to 13:11.68 in 2020, his first year with the BTC. In 2021, he added the 10,000m to his repertoire and recorded year’s bests of 13:02.53 and 27:11.29 in the two events he ran in an impressive 2021 Olympic double. In running 4.23 percent slower for the 10,000m distance, he was looking more like a J-Chep/Kenny B/Haile G sort than a Purdy guy.

I thought Fisher would just miss Rupp’s record of 26:44.36 from 2014, an idea based mainly on how sad it would be for Rupp to lose two national records in such a brief time to the same guy, one who wears a uniform Rupp reportedly doesn’t like. Had I used Fisher’s recent 12:53.73 as a jumping-off point, and gone with 4.23 percent as a slowdown factor, I would have come up with 26:53.

On the ground, Fisher ran 26:33.84, splitting 13:23-13:10. He ran that 10,000 meters in San Juan Capistrano within 3.0 percent of the pace of his 12:53.73 (actually 2.997 percent). If nothing else, all of the otherwise boring numbers in this post should have convinced you how unusual this is. If this “problem” is “corrected” by assuming Fisher will run a far faster 5,000 meters in 2021, he needs to run better than around 12:48 to not remain a Gidey-esque or Huddle-like statistical oddity. Gidey will probably run a lot faster than 14:06.62 shortly, and Huddle surely had more in her than 14:42.64 for 12.5 laps on that fantastic 2016 day in Rio de Janeiro.

13:29 as a collegian to 26:33 at age 24 is impressive, and credit must be given. To exactly whom or what combination of factors, I cannot say with much accuracy or decency.

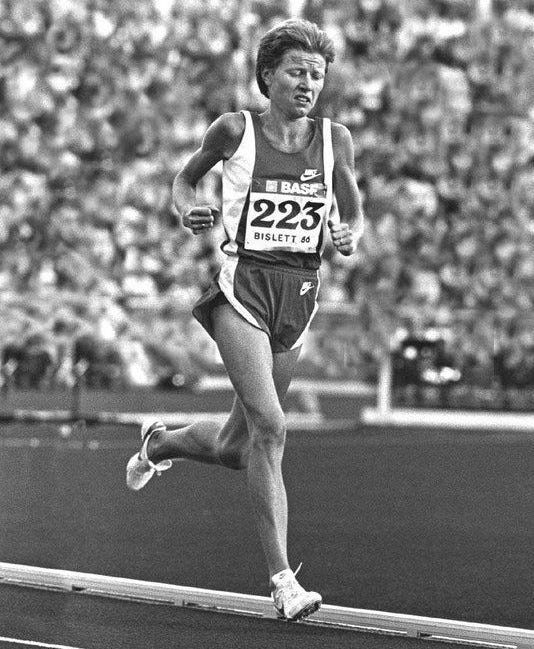

Fisher is now seventh on the all-time 10,000m list. Of the sixty-nine men to ever break 27:00, only three were born outside Africa, and all three are Americans: Fisher, Rupp, and Chris Solinsky. Cranny, meanwhile, moved up to 24th all-time in that event, behind seventeen African-born athletes; three Chinese who were assuredly dirty, and probably still glow in the dark; and Radcliffe, Huddle, and Ingrid Kristiansen of Norway.

Somehow, a few Americans are finding a way to keep themselves relatively close to the best in the business, allowing for the fact that Ethiopians (including Dutch ones) will keep running close to 29-flat until someone decides it’s okay to intervene on a Third World doping jamboree.

The show is proceeding nicely.

Random prediction: Next year Ryan Hall will make a masters comeback and run a 2:09 marathon, whereas Sara Hall will disappear for a while, then return with a bench press of 225 pounds and no traces of backne.

(Photo: Norway’s Ingrid Kristiansen en route smashing her own 10,000-meter world record by nearly 46 seconds with a 30:13.74 at the 1986 Bislett Games in Oslo. Courtesy of sporting-heroes.net.)

This calculator-estimator, which brings back message-board memories from the turn of the century, appears to predicate its unseen computations on Purdy data.

Geoffrey Burns has just written a superbly detailed explanation for the speediness of B.U.’s indoor track.