The curious endurance of the Balboa Park cross-country course

Times at the original showcase for the nation's top young harriers have remained surprisingly consistent over the decades

The 2021 Eastbay National Cross Country Championships were held at Balboa Park in San Diego on Saturday, bringing together 80 of the country’s top high-school runners. Both races were competitive almost to the wire, with Riley Hough taking the boys’ event in 15:11.4 and Natalie Cook again defying seemingly adverse biomechanics to prevail among the girls in 17:15.0.

Both winners had competed the previous Saturday at the Garmin RunningLane XC Championships in Alabama. There, Hough had placed fifth—his first loss of the season—in 14:10.56, making him the first runner across the line to not break Dathan Ritzenhein’s 2000 national cross-country 5K best (14:10.4). Cook, meanwhile, won for the second week in a row in reverse, notching the second-fastest-ever U.S. prep girls’ cross-country time (16:03.93).

Of interest is that Hough’s and Cook’s times at Balboa Park were far off their Alabama times, and by similar amounts, with Hough being 7.15 percent slower in San Diego and Cook slipping by 7.37 percent. In addition to creating a bad joke about never being able to fully trust Garmin data, this should leave us* wondering why two historically fast athletes didn’t come remotely close to the best-ever times at Balboa Park.

By itself, that in fact might mean little to nothing. Conditions just may have been deceptively slow at Balboa, or perhaps both Hough and Cook—their winning performances on the day and youthful resilience notwithstanding—were gassed after long, relentless 2021 autumns. But this pair of “slow” times in San Diego is part of a greater pattern that, at least on its surface and seemingly below it, defies a strong U.S. high-school trend.

The national championship races of the four-region Eastbay series were first run in 1979 in the same location as the Kinney National Championships. They have been run there every December since with the exception of 1981-1982 and 1997-2001, held instead in those seven autumns in Orlando, Florida. With no Eastbay series held in 2020, this means that the national championships have now been run at Balboa Park 35 times.

Foot Locker sponsored the series between 1993 and 2019, so the series is now on its third name. And in 2005, the year after the birth of the NXN series, the national finals fields were expanded from 32 boys and girls, the number in play since 1981, to 40. But the same basic course has been in play since the inception of the national championships. Sufficient changes, however, were made both between 1979 and 1980 and between 1980 and 1983 (when the championships headed back west) to justify discounting pre-1983 data. That means there are 33 “useful” years for comparing times run at the Kinney-Foot Locker-Eastbay National Championships. Whether the course has been “exactly” the same underfoot at a granular level all those years seems at least debatable.1

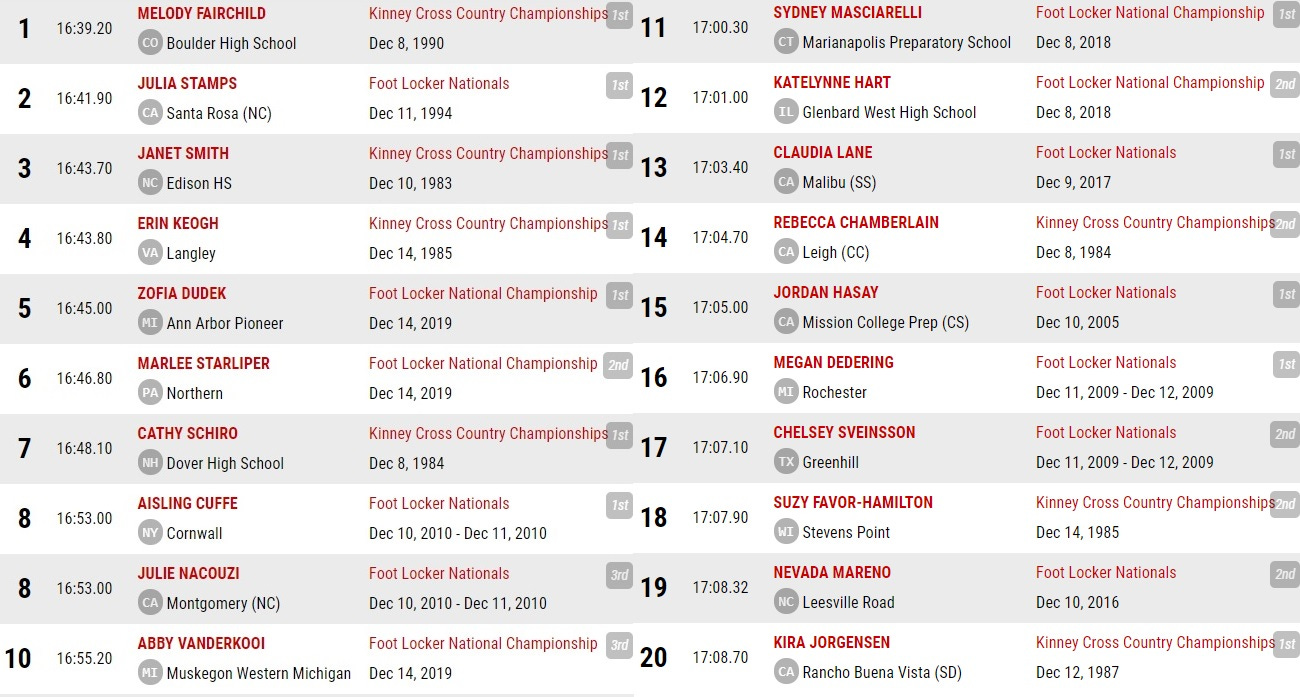

Those with Milesplit Pro access can peruse deep lists of the best-ever boys’ and girls’ times at Balboa Park.2 Those without can see the top twenty times for each sex by either squinting at or clicking on the images below.

Of the top 20 Balboa Park boys' times, twelve are from the 1980s (in seven races), two are from the 1990s (ditto), three are from the "oughts" (in eight races) and three are from the 2010s (a full ten races). There was no 2020 event, and Saturday's contributed nothing new to the list. So, of 33 analyzable Balboa Park races, a curious number of those yielding fast boys' times are from early in its history.

The same thing is true, albeit to a far lesser extent, on the girls' side: Six of the fastest twenty times are from the 1980s, two are from the 1990s, three are from the "oughts," and nine are from the previous decade.

If you go further down the boys’ and girls’ Balboa Park lists at those unfollowable-for-many Milesplit links, you see a lot more 20th-century times than seem appropriate. Sure, it's a one-off every year, but still, 33 one-offs apiece for boys and girls is a lot of chances to run fast times. There is no reason to hold back and there is only so nasty the weather can be in San Diego.

Everyone knows the course is slow. The question is, why have really good high-school distance runners become increasingly proficient at everything over the decades besides throwing town faster times at Balboa Park?

A different question arising from the same set of numbers might be, "Why weren't the 3,200m/2M times of yesteryear better?" Over a hundred U.S. boys have now broken 8:50 for 3,200 meters outdoors, counting two-mile conversions, and the overwhelming majority of them have done it in the current century. Why have so few of them apparently not had what it takes to get under 14:55 despite proving they have “sufficient” track prowess before they graduate? (One guess: A lot of old-schoolers from smaller states never got into truly fast track races until they reached college.)

Obviously, the introduction of the NXN series in 2004 has influenced who even runs in San Diego every fall. But it’s unclear whether it has sucked away much top-tier talent from the Eastbay series, given the traditional lack of significant overlap between premier teams and top individuals and the option for sufficiently fast runners to land in both the national finals of both series.

I may be significantly underestimating the number of great individual athletes who have focused solely on the NXN series, such as Katelyn Tuohy. The Swoosh people must offer better swag. But either way, given the way track times have come down at the close-to-national-record level in the distance events—all before superspikes, mind you, for which cross-country yet lacks a version—it seems odd that so few runners from the past ten or so years claim all-time top-100 or top-25 slots, even if it’s not necessarily strange that records haven’t been smashed to the point of sending their now-wheelchair-bound former holders back to assisted living devastated. Some of the fastest-ever boys and girls in the mile on up, such as Craig Virgin and Lynn Bjorklund, were long out of high school before the Kinney series arrived, leaving their Balboa capabilities up to dreamy speculation.

Maybe the biggest culprit is a combination of two as-yet unmentioned factors: A very long cross-country season, one now loaded with more high-pressure racing opportunities (e.g., Desert Twilight, Great American, any Colorado midseason invitational) than in days of yore, and how ugly the Balboa Park course can bay for anyone not enjoying a magical day. That is, a runner stricken by that not-so-fresh feeling after the gun goes off might run 14:50 on the track instead of 14:35, but on a beastly layout, that slide can be closer to 45 seconds than 15, all else the same.

Lize Brittin qualified for two national finals in the 1980s, winning the Midwest Regional as a senior and placing seventh among 32 runners in San Diego in a time that, thirty-seven years later, would have gotten her 12th in Saturday’s 40-girl field. Asked about the surprising stability of the Balboa Park times, and exercising her right to exist and be heard in the running space, she says, “[I would guess] fatigue from too long a season and that hill is a nightmare. It's way too steep. I love hills, but not ones like that, short and super steep.”

In the past, a typical pattern for elite high-school cross-country runners was to do nothing but train for their Kinney Regional race after their state meet, a gap of several weeks or more in most states. Now, even runners who plan to skip the NXN Nationals still run in the pertinent regional race, because why not? Those are all prestigious competitions in their own right. But perhaps all of the add-ons over the decades that have livened up the “regular” high-school cross-country season, including the creation of competitive networks spanning state borders, have ultimately made it difficult to produce extra-special results on Balboa Park’s uniquely taxing layout.

These are actually performer lists, not performance lists. But very few kids have recorded more than one top-fifty performance at Balboa Park, so the difference in this case is practically irrelevant. (Of the 27 boys to break 15:00 on the course, Ed Cheserek and Marc Davis are the only two to do it twice.)