The Mile High Mile ascended to multiple new levels last night

Despite a shortage of candlepower, the organizers made this an event worth watching (and from the looks of it, worth running)

Last night, the Boulder Road Runners staged what it billed on its website as the fifth annual Mile High Mile,1 which actually features not one but over a dozen one-mile track races. I went and watched, so I’m issuing brief remarks on the affair despite (NON-SPOILER ALERT) not having access to the official or unofficial results, which the BRR will probably post sometime today.

I am therefore persisting with this post despite lacking bits of information some would frame as vital to the post’s mental health. Be assured that none of what is below qualifies as either bullshit or nonsense, unless one places innocent guesswork into either category; some say guesswork should enjoy both labels, which is rhetorically impossible and thus bullshit and nonsense (a combination even lower on the truth-scale than either “bullshit and more bullshit” or “nonsense and more nonsense”).

If memory serves—and it’s rumored to sometimes serve others—the first of these aerobic shindigs was held in 2018. Before last night, the elite races at the Mile High Mile had not produced a swell of genuinely elite times, even allowing for the altitude. In 2018, the winning times were 4:15.99 and 4:48.03; in 2019, they were 4:15.16 and 4:44.08; in 2020, covid-19 swept both races in zero point kiss my ass; in 2021, the winners—with “superspikes” presumably appearing here for the first time—ran 4:06.11 and 4:38.84 (with only three women competing in the elite division); and last year, the top placings were secured in 4:08.10 and 4:51.47. For reference, the Colorado state high-school boys’ and girls’ records for the 1,600 meters, 4:04.36 and 4:39.94, convert to about 4:05.8 and 4:41.6, respectively, for the mile.

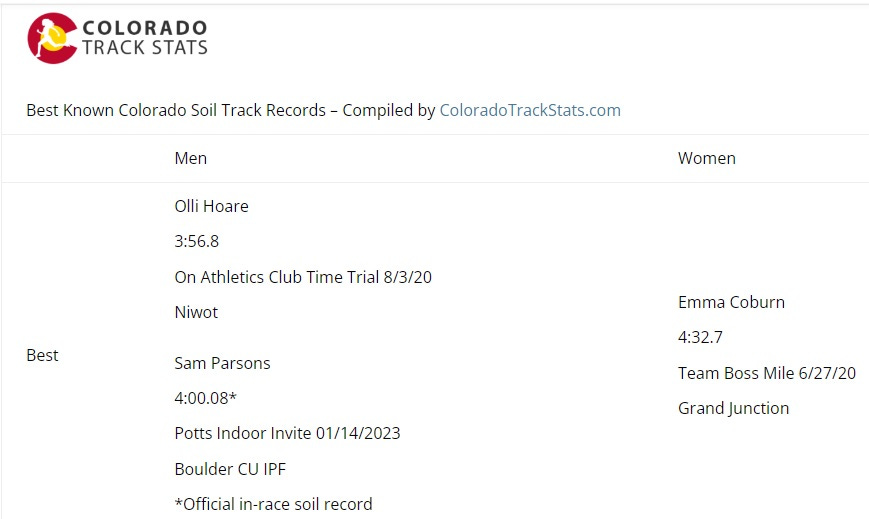

The 2023 Mile High Mile elite races included explicit attempts to break the official men’s and women’s all-comers state records for the distance. Coming in, the women’s record was 4:32.7, run by Emma Coburn at the Team Boss Mile in Grand Junction in June 2020. On the men’s side, there appears to be some dispute over whether the times run by Ollie Hoare and Joe Klecker in August 2020, 3:56.8 and 3:58.4, should be record-eligible because they were delivered in an On Running hand-timed intrasquad time-trial.

There is also apparently some question in at least one observer’s mind over whether the duo’s coach, Dathan Ritzenhein, had his charges run four laps of Niwot High School’s 400-meter track or whether he set up a proper mile by establishing a temporary starting line 9.344 meters or so behind the start/finish line. Hoare’s Athletics Australia bio doesn’t help, because it’s both imprecise and unintentionally confusing regarding the feat:

In an unofficial race he also clocked the first sub-4 minute mile (3:56) at altitude (1600m) in Colorado.

At first, I took (1600m) to be the race distance and not the altitude despite the set-up of the sentence; I only believe this is forgivable because I caught it before publication—otherwise I’d have wandered outside and started keying parked cars. 1,600 meters is 5,250 feet. Duh (although, as you’ll soon see, this overstates the actual altitude by around 90 feet).

To continue playing the shitbird’s advocate, the track at Niwot High, which is about ten miles northeast of Boulder, is a standard 400-meter construct, not marked for the staging of a one-mile race. At least this was the case ten months after the intrasquad time trial took place.

I’m certain Ritz knows how to conduct a mile race, or time-trial, on a metric track; all he needs is access to a tape measure and some chalk or electrical tape. But I couldn’t find a YouTube video of the time-trial, so there is no evidence this is what he did and at least few suggestions this “mile” might have been 9.344 meters short of its advertised distance, among the way this story reports the time-trial splits.

If the time-trial was really only 1,600 meters—and if video or other suitable evidence surfaces to refute this, I’ll feel suitably like a shitbird—Hoare’s and Klecker’s corresponding mile times are 3:58.2 and 3:59.8. In any case, while it’s been conclusively demonstrated that a sub-four mile is possible in Colorado, Hoare’s mark doesn’t seem ratifiable, inasmuch as “Colorado all-comers mile record” has a formal oversight committee anyway.

But for purposes of the 2023 Mile High Mile, the men’s state record at the onset of the event was the fastest time ever run in an in-state mile race, Sam Parsons’ 4:00.08 from January inside the C.U. practice facility, which is about 5,350’ above sea level.

You can see from the Google Earth-generated image above that Niwot High School’s track sits at around 5,160’ above sea level. Also, Grand Junction, where Coburn ran her 4:32.7, is about 4,600’ above sea level.

In years past, the Mile High Mile has been held on the University of Colorado’s track, which lies at 5,260’. But this summer, Potts Field is being renovated, either because Deion Sanders is now coaching the C.U. football team, because the Buffaloes are hosting next spring’s Pac-12 Track and Field Championships, or both.

This resulted in the Mile High Mile being moved to Fairview High School in far south Boulder. This might be the most beautiful venue for a track meet anywhere on the planet, save for the limited seating. FHS offers views of Green Mountain and Bear Mountain, which spike nearly three thousand vertical feet just to the west, basically the very start of the Rocky Mountains at this latitude. The funny thing about the name is that is was imported from Fairview High School’s original location a few miles to the northeast in unincorporated Boulder County. That building has served as Nevin Platt Middle School since the mid-1970s.

The wonderful view was accompanied by a perfect evening for mile racing, warm but not oppressive and almost without wind. Alas, it came with a trade-off, as Fairview’s track sits at 5,512’ above sea level. A 4:00.00 mile at Niwot High is worth about 4:00.25 at Potts Field and about 4:00.75 at Fairview High, according to estimates derived from the NCAA’s altitude-conversion resource. (In this elevation range, gaining 500 feet costs a fast miler about one second.)

I showed up at the track with Rosie at about 8:00, just as the adult open races were getting underway. I met a friend there who, to his credit, has never run a sober step in his life. But he likes to watch things I know more about than he does while asking lots of mostly on-point questions, and I like to reply with extravagant sidebars that occasionally answer some of these questions.

I expected the first over-40 male to run 4:41.7 and the first over-40 female to run 5:24.4 in the combined-gender elite master’s race, which took place just as it was getting legitimately dark and a smattering of tripod-style halogen lights provided the only artificial illumination. I had no idea who was in this race, but I doubt I would have altered my guesses even had I scanned the entry list. My friend decided to take the “over” on both. My guess about the men’s time way off, as Anthony Bruns ran 4:23 or so, but I came close on the women’s side, with something in the low 5:30s topping the category.

That set the stage for the elite races. It also set the stage for a grim announcement, which was that the lights serving the athletic fields, which representatives of the Boulder Valley School District were evidently supposed to turn on, would not be coming on. Thus ensued a scramble that saw multiple vehicle headlights pointed at the track at various angles and various spectators holding cell phones aloft, their flashlight functions activated. These people looked like attendees of some bizarre religious ritual who had forgotten to bring real candles and were just mailing it in. But their efforts worked to offset the descending gloom somewhat.

After the elite women started, when I discovered that my friend was partially in one of these headlight beams, maybe 20 meters up the some straight from the finish line, I decided I would wait for the leaders to come around and then hold two fingers behind my friend’s head to project the shadow of a rabbit onto the field, a time-honored parlor trick no one, if memory serves, had ever tried in this exact situation before. Sadly, we were asked by a member of the lighting crew to relocate a few meters to one side before I could perpetrate this burst of cleverness.

By this point in the proceedings, I had learned that Kaela Edwards was in the race. Edwards finished third in the 800 meters at the recent 2023 USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships, earning a trip to next month’s 2023 World Athletics Championships in Budapest. A 1:59.68 performer at her event of choice, Edwards ran 4:09.08 last month for 1,500 meters in Eugene, Oregon. That’s worth 4:29 on the nose for a full mile—at sea level. To run 4:32.6 or faster at Fairview High School, Edwards would need to run the seal-level equivalent of 4:26-mid or better. (Coburn, that rascal, had only sacrificed about five seconds to the oxygen gods when recording her 4:32.7 on the Western Slope.)

Edwards tucked in behind the pace-setter tasked with going through halfway in 2:15 or so. Also in the race was Roots Running’s Maggie Montoya, one of the few legitimate elites based in the area who’s a fixture at local road and track events. These two opened a gap on the field immediately and kept it.

Edwards passed through 400 meters in around 66 seconds and 800 meters in 2:13-flat on the trackside clock, on pace for 4:26 for 1,600 meters and sub-4:28 for the mile. With one lap to go, she was at 3:23-ish, on pace for 4:31 but going slightly backward after a 68.x lap. Montoya, who is not close to a miler by specialty, made up some of the gap on Edwards in the final lap, but the pair finished in that order, with Edwards clocking 4:33-high or 4:34 and Montoya 4:37 or 4:38. The spectators, allowed owing to the bitchrigged lighting conditions to stand in lane three and form a layer one or two deep of rowdy humans there, had done their best to scream Edwards to the record.

The race also included three or four Japanese women. One of them approached me immediately after she finished the race and stood about one meter in front of me, wearing a huge smile, sweaty and unexpected and extremely female. This doesn’t happen to me often, so it took me a moment to remember that Rosie was sitting patiently next to me, listening to the hubbub and gawking about whenever the noise-level picked up.

“This is Rosie,” I said, refusing to change my accent to suit racialist tropes.

“She’s a girl?” the woman asked, the “r” and the “l” both perfectly audible. She was still breathing quite hard. I started wondering if she had spotted Rosie early in the race instead of right afterward and had considered dropping out just to more quickly meet this charming dog. I would.

“Yes,” I replied, thankful my new friend spoke English and that I therefore didn’t have to root through my brain for any residual Japanese I may have picked up at some point, perhaps in Iowa.

The woman, stroking Rosie’s back more or less like white folks do, went on to disclose that she and some others in the immediate vicinity (I could tell which ones) had just gotten to Boulder two days before, and that she was a middle-distance runner who’d be training in the area until September with some other Japanese nationals.

I don’t even know this much information about my best friends; I have no idea how she did in the race. But she’s obviously happy to be here. I hope no one ruins that for her before I have a chance to. But Rosie likes all people but especially loves attention from female humans, so this was a welcome if quirky interlude.

The men’s race also had a pace-setter and went out just on the slow side of 4:00 pace. I think the leader hit 800 meters in 2:01-low, or 4:03-high one-mile pace. I missed some of the action because my friend was busy explaining that Rosie was the entire reason the Japanese woman had approached me. Like I said, the guy’s a quick study, maybe even a goddamned genius.

With one lap to go, the leader was at 3:02 on the nose, so at a glance a sub-four wasn’t off the table, especially since the man now in front had just assumed the lead and was looking springy. But running sub-4:00 at 5,512’ is like running 3:54-low at sea level, and I didn’t see anyone in this race being able to run a sub-58 last 400 meters up here off the de fact pace this race was moving at.

I was distracted on the last lap by an unruly girl of ten or fifteen so who was busy flinging clods of dirt at Rosie from the practice long-jump pit nearby in an effort to get Rosie to jump at them. This went on for a few tosses before I figured out that Rosie, alongside me on her leash, wasn’t lunging toward insects but toward thrown objects. Whoever the girl’s parents were either unconcerned or not watching. I thought about throwing a clod of dirt at her as a friendly-escalation gambit, but ultimately just stared her down over the course of a brutal forty or fifty unblinking seconds.

As a result, I did not actually see the winner’s time. I do know that the winner was Austen Dalquist of Roots Running and that he did not break Parsons’ official-esque on-Colorado-soil state record-like time.

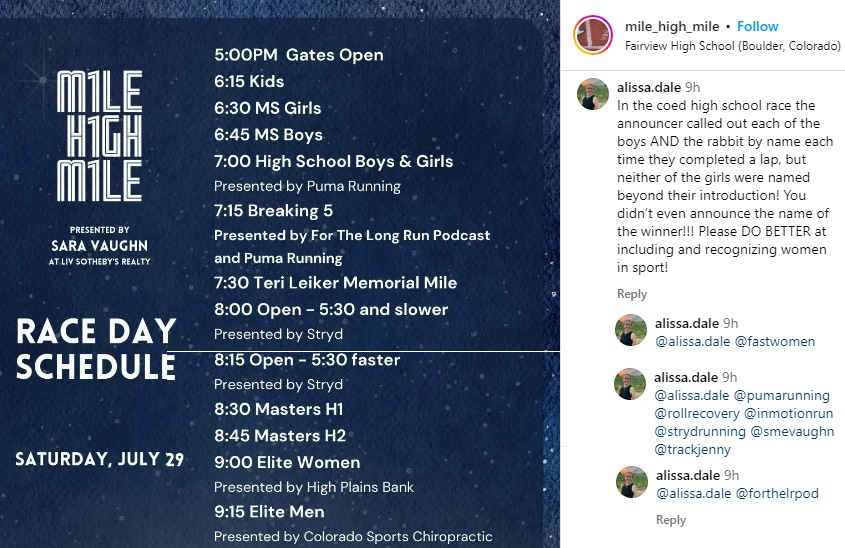

The image below captures a post from the Instagram account of the Mile High Mile. I’m including it mainly because even though the 2023 schedule of events is now of little help to anyone besides Marty McFly and Dr. Emmett Brown, I wanted to indicate the names of some of the sponsors of the event while reserving the laziness to not type these names out. The money they kicked in helped the organizers create some clever and appropriately scaled time-based incentives, and a sub-four for men and a sub-four-thirty for women are both all but assured within the next three to five years.

I’m also including the image because of the pissy comments from “alissa.dale,” who went on to play hall monitor by tagging noted grievance-collectors and multidisciplinary ding-a-lings Alison Wade (@fastwomen) and Jonathan Levitt (@forthelrpod).

The race announcer, Todd Straka, is one of the nicest, most attentive, and flat-out selfless people you will ever meet in this sport, anywhere. Not only is he known for structuring his entire life around the footracing of other people, but he reports as many names as he can when he’s on the mike, even if he doesn’t always know these names in perfect male-female balance in every situation.

This burst of grousing—by someone who, true to form, keeps her own Instagram account private—was paradoxically reassuring. For one thing, I’ve learned that there are really only about six or eight names that appear over and over when it comes to humans I identify as intentional troublemakers, and none other than Alison Desir commands an audience heavy in members with triple-digit IQs or any real influence outside of their own anorgasmic and flabby-peckered online circle-jerks. And when Desir’s dubious star has finally sunk below citizen jogging’s horizon, it won’t be two weeks before even her “fans” forget about her and her antics for all eternity.

And for another thing, those kinds of people don’t tend to show up at track meets if they show up to running events at all. I rarely get out of the house for even this long for anything remotely social, and so it was nice to see last night that track-meet devotees are the same as I have always known them to be around here: scrawny old dudes with their chicken-legged wives; twentysomething dorks with local elite and elite-ish clubs, blissfully unaware this will not be their whole lives forever; single people seated alone except for a single dog, usually on a rise behind the track (and with one and only one of them reeking of booze); affable running-things addict Mike Sandrock racewalking around and perpetually looking like he either just lost or plans to swipe something; beautiful people offering knowing looks to themselves and the trees for no obvious reason whatsoever.

I don’t plan to go watch any more races this year. I’m pro-socially tapped out, and my above-mentioned friend now is both jealous of me and knows at least as much as I do about distance running, so I don’t need to drag him around anywhere else. But if I did, that one bratty kid would probably be heaving dirt-clods at the latest contingent of Japanese women to arrive for endless laps around the Boulder Reservoir. So next time, I can’t just stand by and allow that to happen.

That would have made last night’s event the sixth Mile High Mile(s) if the series had proceeded uninterrupted, but it was in fact interrupted in 2020. So last night was the Mile High Mile’s fifth birthday and fifth running, but alas, “fifth annual” isn’t quite right.